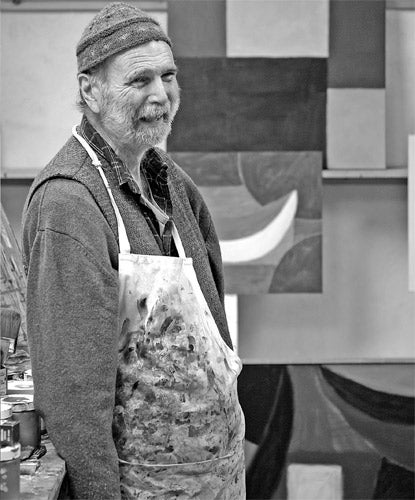

Breon O'Casey: Artist who assisted Barbara Hepworth before becoming a member of the St Ives scene

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Breon O'Casey was a versatile craftsman who eventually made his mark as a fully-fledged St Ives artist. A painter, printmaker, weaver,jewellery-maker and, latterly, sculptor,O'Casey enjoyed a long and successful career that epitomised the thindividing line between the fine and applied arts in South-west Cornwall. In this historically significant regional art centre, craftsmanship proved as important as purely conceptual and stylistic factors.

O'Casey was born in London in 1928, son of the celebrated Irish playwright Sean O'Casey. In spite of his literary background, the young Breon – who moved with his parents to Dartington Hall near Totnes in Devon in 1937 – developed an early interest in the visual arts. He spent the war years at Dartington, an eminently sympathetic environment whose legacy he later described as teaching him to "think with my hands as well as my head".

After the war O'Casey left for London and studied at the Anglo-French Art Centre. The 1950s proved a dark, uncertain time. He found his feet only towards the end of the decade by discovering the vibrant art colony of St Ives. Through the popular sculptor Denis Mitchell, O'Casey met the sculptor Barbara Hepworth, in whose studio he worked for two days a week between 1959 and 1963.

What he described as "a toughapprenticeship" in Hepworth's workshop proved to be his real artistic education. The Irish critic Brian Fallon, author of a 1999 monograph on O'Casey's many-faceted enterprise, pinpointed a "care and patience for materials... and an organic unfussy quality" as the essential qualities learnt by working at Trewyn studios.

During O'Casey's time there, 1950s assistants such as Mitchell, John Milne, Keith Leonard, Roger Leigh and Brian Wall were being replaced by a younger team who were skilled craftsmen in an artisanal, rather than creative, sense. Hepworth ensured that henceforth her "boys" would not confuse their own artistic ambitions with the often more mundane and perfunctory rigours of her imperatives. Perhaps for this reason, O'Casey branched out on his own, and by the mid-1960s had found alternative employment as a schoolteacher in Camborne. He continued, however, to cross paths with his former employer; she respected his determination, skill and endeavour and as well as acquiring a painting of his, commissioned him to make a gold cross which she mounted on a plastic stand and kept on her mantelpiece.

In the early 1960s O'Casey was at the heart of the local exhibition scene as a vice-chairman of the Penwith Society, during one of its most active phases, but it was, in London that O'Casey's work made its most effective inroads. Following a 1966 exhibition at the Signals Gallery, he enjoyed two solo shows with the Marjorie Parr Gallery, Chelsea, in 1967 and 1969. The first exhibition was shared with his St Ives mentor and friend Denis Mitchell; the second had an accompanying catalogue in which Mitchell alluded to the "depth and lyrical qualities" of O'Casey's paintings.

O'Casey's sombre, smouldering palette complemented his simplebut profound symbols, full of themysterious intensity of ancient Celtic hieroglyphics and pagan stone markings. The bronze Relief (1996) used rudimentary shapes which proved that linear incisions on a flat surface could be as effective for sculpture as for a painted composition.

In the creative hierarchy of O'Casey's manifold activities it was perhaps the intensity of the paintings that proved most significant. The osmosis between painting and weaving, which shared a boldness of design and vividness of colour, characterised the equally symbiotic relationship between the painted and graphic oeuvre. In his printmaking, O'Casey utilised his keen feeling for the scratched or inscribed patterns of ancient and primitive art. O'Casey's graphics embraced lithography, linocut and etching, and display his love of French art in general, and Braque, Picasso and Matisse in particular.

In 1996 O'Casey held the axiomatically titled exhibition "The Last Jewellery Show" in Oxford, and after that relinquished the making of brooches, earrings and necklaces – the latter notable for their sophisticated use of variegated stones and metals tightly threaded together like ancient dry stone walls – in favour of sculpture. His sculptures divide into solid bronzes and trinket-like silver objects such as Figure (1996). The latter are light and whimsical in quality and use the flat or conic shapes of the jewellery. The dangling, gently floating mobiles of Alexander Calder were an inspiration for O'Casey's earrings. But in spite of their small scale and use of light materials O'Casey's free-standing sculpted figures are resolutely earth-bound, frontal and static. In this they speak with the tongue of primitive and ethnic art and therefore fulfil O'Casey's desire to produce work with a directness of conception, ease of execution and unaffected power of expression.

O'Casey was a modest man of quiet dignity, temperamentally suited to the slow, patient, painstaking endeavour of the creative craftsman. Despite its struggles O'Casey's career slowly gained the successes it deserved. The association with Marjorie Parr, a dealer whose own roots lay in the glass and furniture trade, proved suitable and congenial – especially after Parr extended her Chelsea base by opening a gallery branch in St Ives in 1969. During the late 1990s his worked was represented by the blue-chip Berkeley Square Gallery, a situation that underlined the growing appeal of his work in a wide variety of guises.

He is survived by his wife Doreen, daughters Duibhne and Oona and son Brendan.

Peter Davies

Breon O'Casey, artist and craftsman: born London 30 April 1928; married 1961 Doreen Corscadden (one son, two daughters); died Penzance 22 May 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments