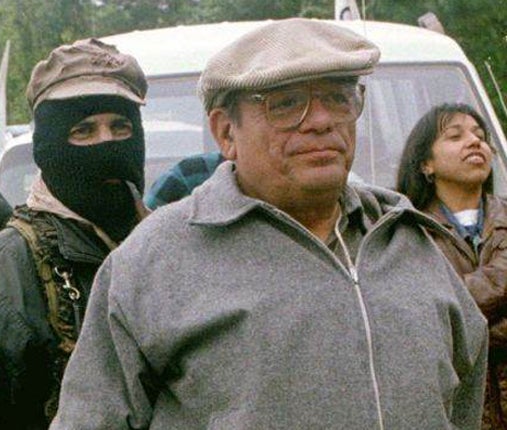

Bishop Samuel Ruiz: Liberation theologian who championed the cause of the Mayan Indians in Mexico

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

When I interviewed Bishop Samuel Ruiz for The Independent in the picturesque southern Mexican town of San Cristóbal de las Casas in August 1993, he told me the poverty-stricken Mayan Indians of his parish were getting restless and some had taken up arms. He introduced me to a young man – "just call me Juan" – who spoke of a new armed group called the Emiliano Zapata Peasant Organisation (EZP0), named after Mexico's peasant and revolutionary leader of the early 20th Century but styled after Peru's Shining Path guerrillas.

A few months later, during the last days of December 1993, I was in Madrid when I got a cryptic call from the bishop's office in San Cristóbal. "Come. Come now!"

After three flights and a long drive, I arrived in the town in the early hours of New Year's Day to find it was being taken over by an indigenous Mayan group calling itself the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN). They had occupied the historic colonial cathedral, and the bishop's office there, but it was clear Samuel Ruiz was no hostage and they were using the cathedral as something of a headquarters. And the bishop himself looked more thrilled than afraid.

Bishop Ruiz, who has died at the age of 86, was a spiritual leader to most of the indigenous Mayans in the state of Chiapas, bordering Guatemala, from the moment he was posted to the area in 1960. Although white and of Hispanic origin, he learned to master three of the Indians' many ancient languages and they referred to him fondly as Tatik – father, in the Tzotzil Mayan language.

But it was the Zapatista uprising that thrust him into the world headlines after he offered himself as a mediator between the guerrillas and the government and Mexican army. He had always told me he opposed violence but, as I followed him around in 1993, he made it clear he knew a guerrilla rebellion was inevitable given the increasing poverty of the local Indian peasants. He was a staunch liberation theologan, pushing the rights of the poor, hence the nickname given to him by the authorities and wealthy ranchers of his region – the Red Bishop. He said he had lost count of the number of death threats he received.

The fighting in Chiapas lasted only 12 days, with 145 dead, mostly in the guerrillas' strongholds of Ocosingo, Altamirano and Las Margaritas, but one of the rebel leaders, the pipe-puffing Subcomandante Marcos, clearly a white man despite what wouldbecome his trademark balaclava, shot to worldwide fame. He insisted hewas only a subcomandante and that the EZLN's comandantes, including the tiny Ramona (Obituary, 11 January 2006), were all indigenous. Buthe became the public face, albeit masked, of the movement, and its eloquent voice.

Bishop Ruiz went on to mediatebetween the EZLN and the government throughout the 1990s although the rebellion largely fizzled out,with government forces gradually taking control of Chiapas towns and pushing the guerrillas deeper into the Lacandon jungle. In reality, little has changed for the local Indians, who are still seen largely as a tourist attraction, selling their embroideries outside the cathedral.

Ruiz once went on hunger strike to press for the rights of his indigenous flock and, in 1997, survived an ambush by pro-government gunmen in which three of his aides were wounded. In a bizarre twist partly due to Ruiz's mediation, Marcos and other guerrillas were eventually allowed passage out of their hide-outs and showed up, still masked, at events around Mexico with a clear understanding that they would not be arrested.

Samuel Ruiz was born on 3 November, 1924, in the town of Irapuato, famed for its strawberries, in the conservative, silver-mining state of Guanajuato. He studied in Rome at the Jesuit-run Pontifical Gregorian University and was ordained as a priest in the Holy City in 1949, when he was 24. After he was made a bishop by Pope John XXIII in November 1959, he arrived two months later in Chiapas, the area where novelist Grahame Greene had made another, though fictional priest famous 20 years earlier – "the whisky priest" in The Power and the Glory.

Ruiz's mandate was to wean the indigenous Mayans away from their ancient ways and towards Catholicism – as well as braking the rise of Protestantism – but he soon found "it was they who ended up changing me." It was a time when the local Indians were treated almost like animals by the white population, the middle class and the wealthy caciques – ranchers and politicians, and were often still barred from walking on pavements. Ruiz began encouraging their traditions, including their languages and colourful embroidered dress, items of which he often wore himself over a western suit. He said the condition of the native Indians had changed little since the Spaniard Cortés first landed in Mexico in the early 16th Century.

He set up a network of rural catechists, or lay bible teachers, who spread out across Chiapas, even into the deep jungle, to allow Indians to participate in worship despite their remoteness. "They are God's people," he once said, "every one of them, just as much as a white person is. But 1,000 Indians do not matter when one white person speaks out."

Ruiz retired to the central Mexican state of Querétaro in 1999 but remained Bishop Emeritus of San Cristóbal de las Casas. He was nominated several times for the Nobel Peace Prize and in 2000 was awarded Unesco's International Simó* Bolivar Prize for "contributing to the freedom, independence and dignity of peoples and to the strengthening of a new international economic, social and cultural order."

PHIL DAVISON

Samuel Ruiz García, liberation theologian and human rights activist: born Irapuato, Mexico 3 November 1924; died Mexico City 24 January 2011.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments