'Baby' Jake Matlala: World champion in two weight divisions who was named as his favourite boxer by Nelson Mandela

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nelson Mandela was four days out of prison when I asked him to name his favourite boxer. "Oh, it has to be Baby Jake," he said, beaming with delight, having been serious and sombre for the previous hour. Yes, Baby Jake Matlala." Soon after, the pair met for the first of numerous times and seemed to relish each other's company, sometimes joking about their size disparity. The world's shortest boxer at 4ft 10in, who died two days after his friend and hero, was the darling of the country's sports-mad public – a crossover figure whose charm and ebullience endeared him to the white suburbs almost as much as in his home crowd in Soweto.

Matlala was also the scourge of Britain's best little men during his eight years of holding various versions of world titles in two weight divisions, making six trips to England and Scotland, disappointing the home fans on each occasion. He was comically small, with a big bald head and an old man's face that made people laugh, and he appreciated the joke. When his opponents saw him for the first time they also tended to smile, until the bell sounded. He'd regularly give away more than six inches in height and a stone in weight, but in the course of his 22-year career he developed a deceptively difficult style. His tight defence and head movement made him extremely difficult to tag and his impeccable timing magnified his power. He was also a teetotaller and an intense trainer, allowing him to throw more punches than any of his opponents.

In 1994, after he stopped London's Francis Ampofo in nine rounds, I asked him to describe his style. He took my hand, as was his way, and beamed. "They come out fast; I start slow, but with every round I step up the pace and the punishment until I'm hitting them as hard as I can and as often as I can move my arms, and because I'm so short I concentrate on the body and I just work it over mercilessly until their resistance is gone."

It wasn't always so. As the only child of a driver and cook, his working class background was hardly desperate, and he said he never had a street fight because "everybody just seemed to like me". He was also top of his class and went on to complete a BComm degree at one of his country's leading universities.

He took to boxing as a 10-year-old "just for fun", won 198 out of 199 amateur fights and turned professional at the age of 18. He sometimes weighed just over seven stone, but the straw-weight division had not yet been introduced so he fought at light-flyweight (7st 10lb). He won most of his fights, but there was one man he couldn't better, a stylist from the Eastern Cape, Vuyani Nene. They fought five times and Nene won all five.

But while Nene partied his way out of the picture, Matlala continued to improve. He finally won the national title and his promoter secures him a challenge for the IBF flyweight title (two divisions above his natural weight), against Northern Ireland's Dave McCauley in Belfast, but he was stopped in 10 rounds.

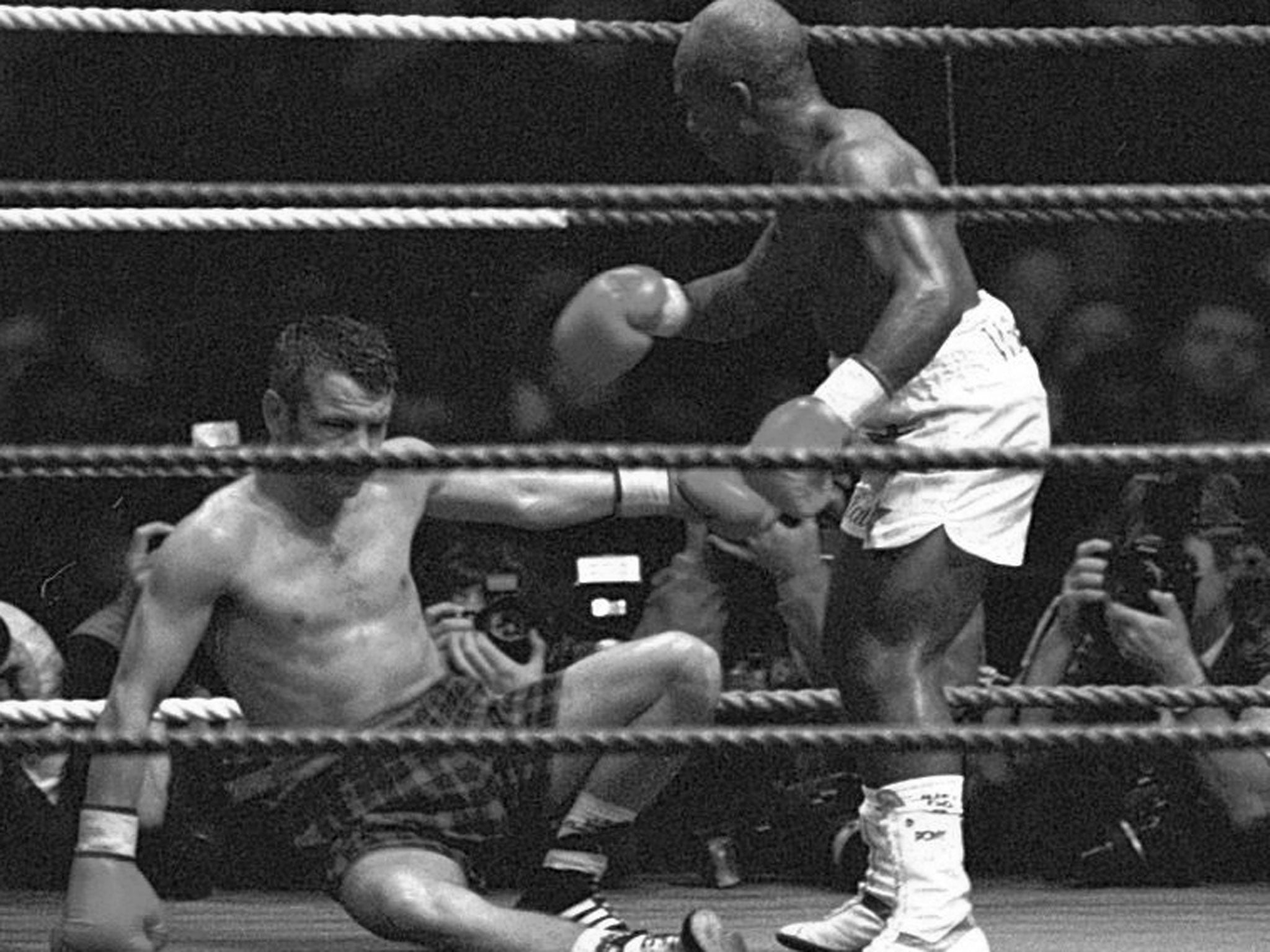

He ironed out his flaws, trained even harder and in 1993 travelled to Glasgow to batter Pat Clinton to defeat in eight rounds for the WBO flyweight title. He defended it three times before agreeing to go ahead with a defence against a talented Mexican, Alberto Jimenez, weeks after intestinal surgery. He lost in eight, suffering from acute abdominal pains.

They said he was finished at the age of 33, but he dropped down in weight, returned to Glasgow and relieved Scotland's Paul Weir of his WBO light-flyweight title, part of a five-year unbeaten spell. The highpoint came in 1997, when he was chosen as an easy opponent for the golden boy of the lighter weights, Michael Carbajal, in a Las Vegas fight screened on HBO. Matlala, 35, averaged 130 punches per round to stop the A-list American in the ninth.

On his last visit to Britain at the age of 39, he overwhelmed the former British flyweight champion, Mickey Cantwell, in five. He retired soon after to pursue his business interests.

There was another side to Jake Matlala. In 1998 he had an extra-marital affair with a singer who then demanded "compensation" in exchange for silence, and settled for R250 000 plus a written admission of guilt to rape – which was then leaked to the local press. Matlala said he only agreed because he was being blackmailed and insisted the fling with the singer was entirely consensual. "I know it wasn't a good thing to do," he told me, "but I wanted to avoid all that publicity because I needed to protect my family and my reputation."

This business seemed to have no impact on his immense reputation at home and he continued to prosper and to visit Mandela. But over the last five years his health declined, with regular visits to hospital for pneumonia, depleting his financial reserves.

Jacob Matlala, boxer: born Soweto 8 January 1962; married Mapule (two children); died 7 December 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments