Anthony Blond: Bold and imaginative publisher with an infectious love of life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.'Although his career was flawed by intemperance, volatility and quarrels, this did not prevent his acquiring a large and, on the whole, affectionate acquaintance among all sorts and conditions of men and women." So wrote the publisher Anthony Blond in the draft obituary of himself which he included in his autobiographical Jew Made in England (2004).

Whether or not that may be thought an accurate assessment, the obituary was over-optimistic in one respect, for he gave himself until 92 and finished himself off in his beautiful house in Galle, Sri Lanka. In fact he died in his 80th year, in hospital in Limoges, near the house in Bellac where he had lived with his wife Laura for the past 25 years. The large circle of friends did and does exist, and most of them found it not too hard to forgive him his bouts of bad behaviour because his love of life was infectious, and he was often very funny indeed.

Anthony Blond was born in 1928, the elder son of Neville Blond, who had been a major in the Second World War and was later the founder of the Royal Court Theatre. Anthony's mother, Reba Nahum, also came of an established Jewish family in Manchester, and was the sister of Baron Nahum, the photographer. Anthony was educated at Eton and New College, Oxford.

He was briefly conscripted into the Army to do his national service, but soon registered as a conscientious objector. His pacifist views were sincere; his left-wing beliefs more fluctuating. He did stand as Labour candidate for Chester in the general election of 1964 and considerably raised the Labour vote, but was the first to admit that he wanted the palm without the dust.

He did not much enjoy Eton but he enjoyed Oxford excessively, to the extent that his History exhibition to New College was removed, academic study seeming to him so much less attractive than other pastimes. He started a magazine called Harlequin which enjoyed considerable success and frequently flirted with scandal. He did, however, reject a poem by Antony de Hoghton, one of the outsize personalities of the time, which began "God was in his garage, cranking up his Bentley". De Hoghton, piqued, took the poem to Cambridge, where Mark Boxer did publish it and was duly sent down for blasphemy.

After Oxford Blond worked briefly for Raymond Savage, a literary agent who soon retired, failing to leave his clients in Blond's hands. Blond, undaunted, in 1952 started his own agency. Not untypically he asked me, whom he had just met, to be his partner. I invested all of £50 and we set up Anthony Blond (London) Ltd. I was too shy for what I think was not yet called networking, so I did the typing, kept the accounts and wrote what must have been deeply disheartening reader's reports, so impossibly high were my standards.

Anthony ranged about in the literary world and came back with tales of best-selling escape stories and now long-forgotten royal memoirs. We found our own wartime escape story through Sir Archibald McIndoe, the plastic surgeon, a neighbour and friend of Anthony's father and stepmother Elaine, sister of Sir Simon Marks. Boldness Be My Friend by Richard Pape, one of McIndoe's patients, was published in 1953 by Paul Elek and joined a few other such Shakespearean titles – Airey Neave's They Have Their Exits was one – in the best-seller lists.

We had other pieces of luck, a few failures and much amusement, until we wound the whole thing down when Anthony Blond became a publisher himself, briefly joining Allan Wingate before setting up on his own in 1958. His earliest books included Simon Raven's The Feathers of Death (1959, the first of a long succession of Raven novels for Blond) and A History of Orgies (1958) by Burgo Partridge, son of Ralph and Frances Partridge, which – beyond the dreams of the rest of us – was sold in the United States.

Blond wrote two good books about the publishing trade, The Publishing Game (1971) and The Book Book (1983). He also wrote an amusing novel, Family Business (1978), which caused a rift with his stepmother, who found it too close to the story of the founding families of Marks & Spencer. In 1994 he wrote Blond's Roman Emperors, a lively if not always accurate account of the Caesars. He was involved in the early days of Private Eye and in the Manchester commercial radio station Piccadilly Radio.

As a publisher Anthony Blond was bold and imaginative and good at initiating ideas which he expected others to follow through. Blond Educational, which he started in 1962, was a pioneer in the field of school textbooks. He published Spike Milligan's first novel, Puckoon, in 1963; other bestsellers included Harold Robbins's The Carpetbaggers and William Peter Blatty's The Exorcist. He commissioned E.F. Schumacher's Small is Beautiful (1973), whose title was his invention: it became one of the most influential books of its time. In due course Desmond Briggs, who had worked for the firm for some time, became a partner and the firm became Blond and Briggs, but Blond's interest was waning and finances bored him. There was a brief further existence as Blond, Muller and White but before long and not without some acrimony, in 1987 Anthony Blond's publishing career came to an end.

In 1955 he had married Charlotte Strachey, daughter of John Strachey and the novelist Isobel Strachey. She had inherited her father's complexion (he had been known in Bloomsbury as "spotty John"). Anthony took her to the most expensive dermatologist in Harley Street and she became a beauty and a part-time model. They lived in a handsome house in Chester Row, with the publishing office in the back room, but the marriage was put under strain by a series of miscarriages and a tragic stillbirth. Charlotte left quietly one day with the journalist Peter Jenkins, whom she subsequently married.

For 14 years Blond shared his life with Andrew McCall, with whom he created a beautiful house in Corfu, as well as continuing to live and entertain in Chester Row. In 1981 he married Laura, daughter of Roger and Lady Mary Hesketh, in a picturesque ceremony in Sri Lanka, where they had found a fine Dutch Colonial house in Galle. He and Laura adopted a Sri Lankan orphan, Ajith, and in 1989, finding themselves driving through a French village called Blond, they decided to move there. In the event they bought a house in the nearby town of Bellac.

Isabel Colegate

I first met the Bentley-driving, boat-rocking Anthony Blond in the house of his sometime mother-in-law Isobel Strachey, writes Andrew Barrow.

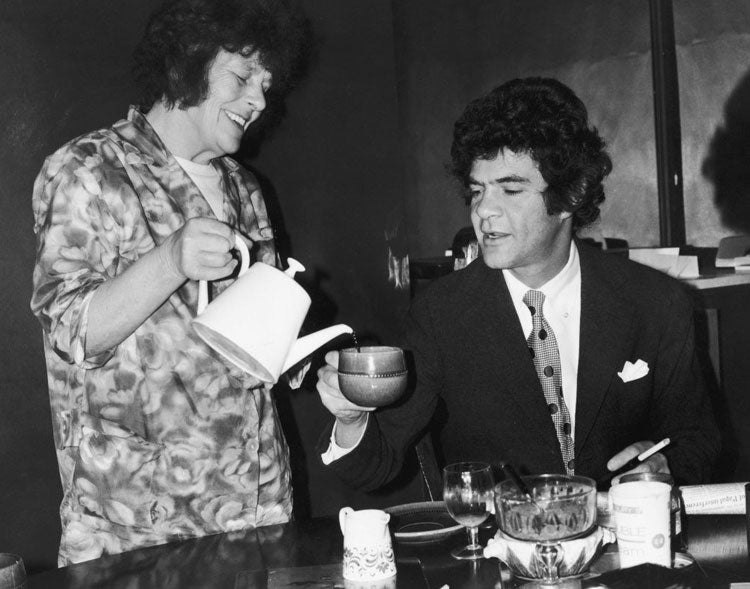

Almost every other night at the end of the Swinging Sixties, she gave a party in her L-shaped drawing room in Oakley Street, Chelsea. Accompanied by his glamorous young friend Andrew McCall, author of The Au Pair Boy, with whom he lived between his two marriages, Blond made a bouncy, punchy, almost showbiz entrance. I already knew about his fame as a publisher. I soon learnt that he was also part of a wild and witty circle of knockabout friends, who included the Joan-of-Arc-like Philippa Pullar, author of Consuming Passions, the American-born clergyman Charles Sinnickson, widely known as "the Vicar of Chelsea" and the future TV chef Jennifer Paterson.

Alas, Blond would soon reject my first attempt at a novel with the stern words "Too much self-pity. Go out and get at 'em." On a much happier note, he later taught me how to make dry Martini, a process which he insisted involved putting the glasses themselves into the freezer.

Anthony Bernard Blond, publisher and writer: born Sale, Cheshire 20 March 1928; married 1955 Charlotte Strachey (marriage dissolved 1960), 1981 Laura Hesketh (one adopted son), (one son with Cressida Lindsay); died Limoges, France 27 February 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments