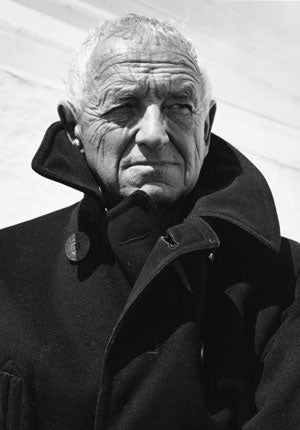

Andrew Wyeth: Painter who enjoyed huge commercial success but was dismissed by the majority of critics

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The American painter Andrew Wyeth, who has died aged 91 in his sleep at home in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania after a brief illness, was one of America's most controversial and beloved artists. In popular and commercial terms he is among the most successful painters in the history of art. In critical terms the jury is out.

Wyeth is derided for his patronising attitudes to the rural disadvantaged he so often painted, the banality of his imagination and his anachronisticattitudes, his overwhelming popularity another stick with which to beat the art. Critics complain of his apparent nostalgia for a rural world of puritan, hard-working values that in reality never was.

Wyeth was the youngest of fivechildren, the second son of the wildly successful illustrator N.C. Wyeth – as well known as Tenniel, Arthur Rackham and E.H. Shepherd in Britain – whose imaginings of Treasure Island, among other classics, informed American childhood. The family lived in Chadds Ford in the Brandywine Valley, the landscape of which was to surround him all his life, and, heavily edited, informed his art.

In childhood too fragile to go to school, he was educated at home. Two of his sisters were also to become professional artists and it is thought that his brother-in-law Peter Hurd, a fellow pupil of N.C. Wyeth and who became a massively successful Western painter of New Mexican scenes, introduced Andrew Wyeth to tempera. The art of Winslow Homer convinced Wyeth of his own vocation, while the other great 19th century American artist he admired unreservedly was the superb realist (and virtuoso painter in oils) Thomas Eakins.

By his mid-twenties he had taken part in a seminal exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art, "American Realists and Magic Realists", curated by the legendary Alfred Barr, champion of Matisse and Picasso, and seven years later he took part in a mid-century retrospective, "100 American Painters" at the Metropolitan. He was almost obsessively championed by the provocative Thomas Hoving, director of the Metropolitan – who curated Wyeth's first retrospective show of a living American artist ever held at the Metropolitan – and admired by writers such as John Updike.

Simultaneously he has been regularly dismissed by the majority of critics as too popular, sentimental and reactionary, particularly in his choice of rural subject matter, from farming landscape to farming folk, devoid apparently of the appurtenances of modern life. One of the canniest assessments is that of Robert Rosenblum: Wyeth was "at once the most overestimated painter by the public and the most underestimated painter by the knowing art audience ... a creator of very very haunting images that nobody who hates him can get out of their minds."

Unlike that other memorable chronicler of Americana, Norman Rockwell, Wyeth eschewed narrative andanecdote, and also all offers to illustrate magazine covers. Instead heconcentrated on painting in mesmerising detail the landscapes of agricultural Pennsylvania and coastal Maine, inhabited exclusively in Wyeth's world by working farmers, their families and helpers. The socially disadvantaged, the rural underclass, were also to feature.

Drifters and the mentally disturbed inhabited Wyeth country, which also focussed on two families: the crippled Christina Olson, her brother Alvaro, and their environment in Cushing, Maine, the summer destination of Wyeth and his family for 30 years; and the husband and wife Karl and Anna Kuerner, farmers of Chadds Ford. Karl was a German who had fought in the First World War, his wife Anna eccentric, possibly mentally disturbed.

The one Wyeth owned by New York's Museum of Modern Art, Christina's World (1948), is the best known American painting of the 20th century. It is perhaps typical of Wyeth's darker side; it shows a crippled woman in her 50s, Christina Olson, dressed in an acid pink dress and crawling through a luminous field towards an 18th century farmhouse on the horizon. The setting is near Cushing, Maine. Christina's World, nearly four foot wide, is tempera on gessoed panel. It was bought for $1,800 and is permanently on view, an incongruous sight in the midst of the avant garde-isms of modern times. "The challenge to me was to do justice to her extraordinary conquest of a life which most people would consider hopeless," Wyeth said. "Limited physically but by no means spiritually."

The composition is embedded in the national psyche and is often used as the recognised basis for illustration, cartoon and caricature, (as are other iconic images such as Grant Wood's 1930 American Gothic). Christina herself became so famous through Wyeth's image that there were national obituaries when she died in her 70s. When the staff of MOMA went on strike in 1971, their poster showed Christina's World with the word "STRIKE" issuing forth in a balloon from the emaciated, tenacious figure of Christina inching forward through the unploughed meadow.

Wyeth went on to have two more muses, both women. The first was the young Siri Erickson, a Maine native, whom he painted nude in a tempera called The Virgin when she was 15. And then an enjoyable scandal erupted with a 1985 exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, championed by its charismatic director, J Carter Brown, "The Helga Pictures".

The story at the time was that Wyeth had secretly been paintingHelga Testorf, a neighbour in Pennsylvania and a married mother of four, from 1970 to 1985, portraits both nude and clothed. Wyeth's wife Betsy said it was love, and speculation raged about a secret affair; in the light of thepublicity and exhibition 240 of the Helga paintings and drawings were sold in 1986 for $6m to a commercialpublisher, Leonard Andrews, who in turn sold a selection on to a Japanese collector for millions more. The critic Robert Hughes characterised the whole episode as "The Great Helga Hype", and Time magazine reported that some of Wyeth's Pennsylvania neighbours thought the manipulated publicity a commercial scam.

The Pennsylvania winter landscape was bleak, dun and earth colours predominating, the houses old, austere, empty; Wyeth's depictions were pared down, the colours bleached. Even Maine in the summer shared the same lack of colour, in this case grassy fields bleached by the sun. His preferred media were threefold: watercolour; dry brush watercolour, an arduous and painstaking technique using very small brushes with most of the moisture squeezed out; and tempera, dry pigment mixed with distilled water and egg yolk, the paint medium which antedated oil. The supports were therefore either paper for watercolour or panel for tempera.

In May 2007 Christie's New York sold another tempera, the Maine-set Eriksons (1973), depicting a working man in an empty farmhouse, for $10.3m, currently the record for a Wyeth. The paradox had become a millionaire artist painting a way of life long gone, eschewing, except for one uncharacteristic study of the inside of a private jet shown three years ago, any notion of contemporary life, from cars to cityscapes. Unlike the restless pattern of most American artists who migrated to New York and other cities, Wyeth rarely travelled beyond Wyeth country, and made his first visit to Europe at the age of 60 in 1977.

His work is held in the most prestigious public collections in the United States. Wyeth was the first living American artist to be exhibited in the White House, in 1963, when he was the first artist to receive the Presidential Freedom Award, given by President Kennedy; he was the first American artist to have a retrospective at London's Royal Academy (1980). He was on the cover of Time magazine in 1963 and in 1985 both Time and Newsweek carried rival covers of Helga paintings.

"Art to me, is seeing. I think you have got to use your eyes, as well as your emotion, and one without the other just doesn't work. That's my art," was Wyeth's credo. The jury is still out on the aesthetic value and quality of Wyeth's art: time will tell.

Marina Vaizey

Andrew Wyeth, artist: born Chadds Ford Pennsylvania 12 July 1917; married 1940 Betsy Merle James (two sons); died Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania 16 January 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments