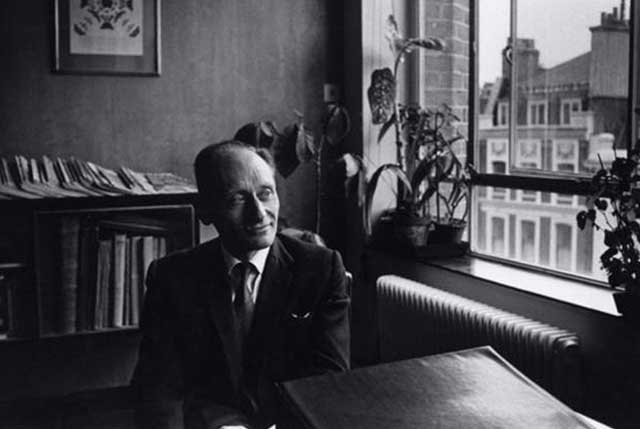

Alex Kroll: Designer and art director at 'Vogue' and 'House & Garden'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Alex Kroll was a member of that select band, who, in escaping to England from the pogroms and persecutions of the 1930s, at the hands of Communists and Nazis alike, came to add incalculably to English cultural and intellectual life. A graphic designer by training, he made his entire career with the magazine publisher Condé Nast, as art director, editor and finally, from its inception, as director of the group's publishing arm, Condé Nast Books. From first to last, albeit with unvarying discretion and modesty, ever concerned to encourage and bring on those who worked under and with him, he left his own indelible mark on everything he touched. If there was always room for visual interest, innovation and even excitement, the cheap or vulgar had no place.

The youngest of three children, Kroll was born in Moscow in 1916, into a well-to-do, cultivated and well-connected Jewish family of mixed Latvian and Polish descent. His father, Hermann, had married his cousin, Sophie, read chemistry at Berne University, and been set up by his father as director of a factory on the outskirts of Moscow. Though comparatively unaffected by the Revolution – an uncle, Misha, a professor of neurology, was to have Lenin as a patient – the family then moved into Moscow itself, to a modern flat in a block designed, as it happened, by another uncle, Abram.

There Kroll enjoyed what he remembered as a happy childhood. In 1923, however, when he was seven, first Fanny, his elder sister, died of a complication following whooping cough, and then he contracted TB of the spine which was to mark him physically for life. Somehow his grandmother got permission for him to be taken for treatment to a specialist in Berlin, where he was to spend the next two years on his back in plaster, much of that time, summer and winter, on the hospital verandah.

His father, meanwhile, had moved to the Ministry of Agriculture, from which in the late 1920s he was seconded to the Russian embassy in Berlin. There the family was reunited, for Alex's surviving sister, Natasha (later a distinguished designer for film and television) had been sent to her mother's sister, Stephanie, who, with their father, had escaped after the Revolution and was running a hotel at Wiesbaden. Once safely established in Berlin, their father took the opportunity to defect, and there the children completed their education.

But in 1938, with the political situation growing ever more ominous, Alex was sent to join Natasha in London, where the Reimann School of Art, at which she had been a student in Berlin, had opened a branch. Their parents were to join them, but Hermann Kroll was already in prison, suspected of helping to send money abroad, while Sophie stayed with her sister, waiting for her husband's release. Trapped by the outbreak of war, they were sent to Belsen and then to separate camps, in France and Germany, having promised to meet at Wiesbaden should they survive the war. Miraculously they did survive – Hermann, urged to do so by a British sergeant, had jumped off a lorry to avoid repatriation to Russia – but they met in London. Stephanie died in Theresienstadt.

In 1940 Alex Kroll had married a fellow émigré, Maria Wolff, who was then sent to work in a factory in Yorkshire. Kroll stayed in London, and in 1942, through contacts made at the Reimann School, he joined Vogue, to work in tandem with John Parsons on its design and layout.

The English edition of the magazine had, as it were, a "good war", for though edited and produced on a wing and a prayer, it had official encouragement as being good for morale, and under its remarkable editor Audrey Withers, its standards never dropped, Kroll bringing to it his own distinctive, elegantly disciplined aesthetic. He was particularly sympathetic to the work of Vogue's notable team of photographers, working closely with Cecil Beaton, Clifford Coffin, John Deakin and the young Norman Parkinson, and most especially with Vogue's roving American war correspondent, the erstwhile model and surrealist Lee Miller.

In the early 1950s, he moved as art director to Vogue's sister magazine, House & Garden, then somewhat in the doldrums. A year or two later, in 1957, one of his former tutors at the Reimann School, a fellow spirit, Robert Harling, arrived as editor, and with him, latterly as his deputy, Kroll was to enjoy a remarkable creative collaboration, playing a leading role in the magazine's revival.

Together they had begun the practice of reworking H&G material, theme by theme, into handsome books, so when Condé Nast Books was set up in 1968, Kroll was an obvious choice as editor and director. With the appearance the following year of Goodbye Baby and Amen: a saraband for the Sixties, by Peter Evans with photographs by David Bailey, the venture was an immediate success.

Kroll saw immediately the potential in Vogue's extraordinarily rich, if chaotic archive, mouldering unloved in its damp basement beneath Hanover Square, as being in itself not just a history of fashion but a social history of the century.

It would take him many years to bring the management of Vogue to share his view of the value of what it held – well into the 1980s the damp still came in to glue the pages of the bound volumes together, while a whole roomful of cabinets of negatives and proofs, dating back to the 1940s, was skipped to make way for Tatler's office – yet he prevailed at last, and the long list of books commissioned and published under his direction remains his true memorial. Georgina Howell's historical survey In Vogue, published in 1976 to mark the English title's 60th anniversary, was a landmark, and in encouraging her, and other writers such as Brigid Keenan, Pamela Harlech, Robin Muir, Christina Probert and Jane Mulvagh, his eye and judgement never faltered.

I came to know Alex in the early 1980s through Georgina Howell, an old friend, which introduction led to my writing a series of books on fashion illustration as it had been used by Vogue over the years, a discipline by then all but banished from its pages. He was the most encouraging and sympathetic of editors, and the recollection of my ignorance in the face of his wry, cosmopolitan erudition still makes me blush. Full of fun and friendly gossip, he would give me the most agreeable of lunches – Chez Victor before it disappeared a favourite. Though too much out of touch in recent years, we would sometimes bump into each other at the bus-stop outside his house on the Fulham Road, which is where I last saw him a few months ago. He was the same as ever, which is how I shall remember him: apparently immortal.

William Packer

Alexander Kroll, art director, editor and publisher: born Moscow 21 September 1916; married 1940 Maria Wolff (died 2002; two sons); died London 5 June 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments