The Media Column: Why the left-wing New Statesman is stubbornly resisting the lure of Corbynmania

Editor Jason Cowley says Jeremy Corbyn is as much a career politician as Ed Miliband or George Osborne

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jason Cowley still lives in hope that he might one day publish the poetry of Jeremy Corbyn. The editor of Britain’s most-established, left-leaning periodical, New Statesman, might have a long wait. Earlier this year, Corbyn promised Cowley the verses he unsuccessfully submitted to the magazine in 1968.

Cowley agreed to print the material if Corbyn won the Labour leadership race. But Cowley has made clear in print he is unconvinced by Labour’s new leader, whom he likens to a 1970s sociology lecturer, and Corbyn is probably now looking to place his poems somewhere else.

With Labour’s grassroots re-energised in a way unimaginable the day after the General Election, it might seem misguided – editorially and commercially – for a title founded in 1913 with the intention of “permeating the educated and influential classes with socialist ideas” to so resist the left’s new messiah.

“We were and are deeply sceptical of Corbyn,” insists Cowley in an interview at New Statesman’s offices near St Paul’s Cathedral. “There’s a sense from some readers, I think, that we should be cheerleaders for Corbyn because he represents a challenge to the establishment.

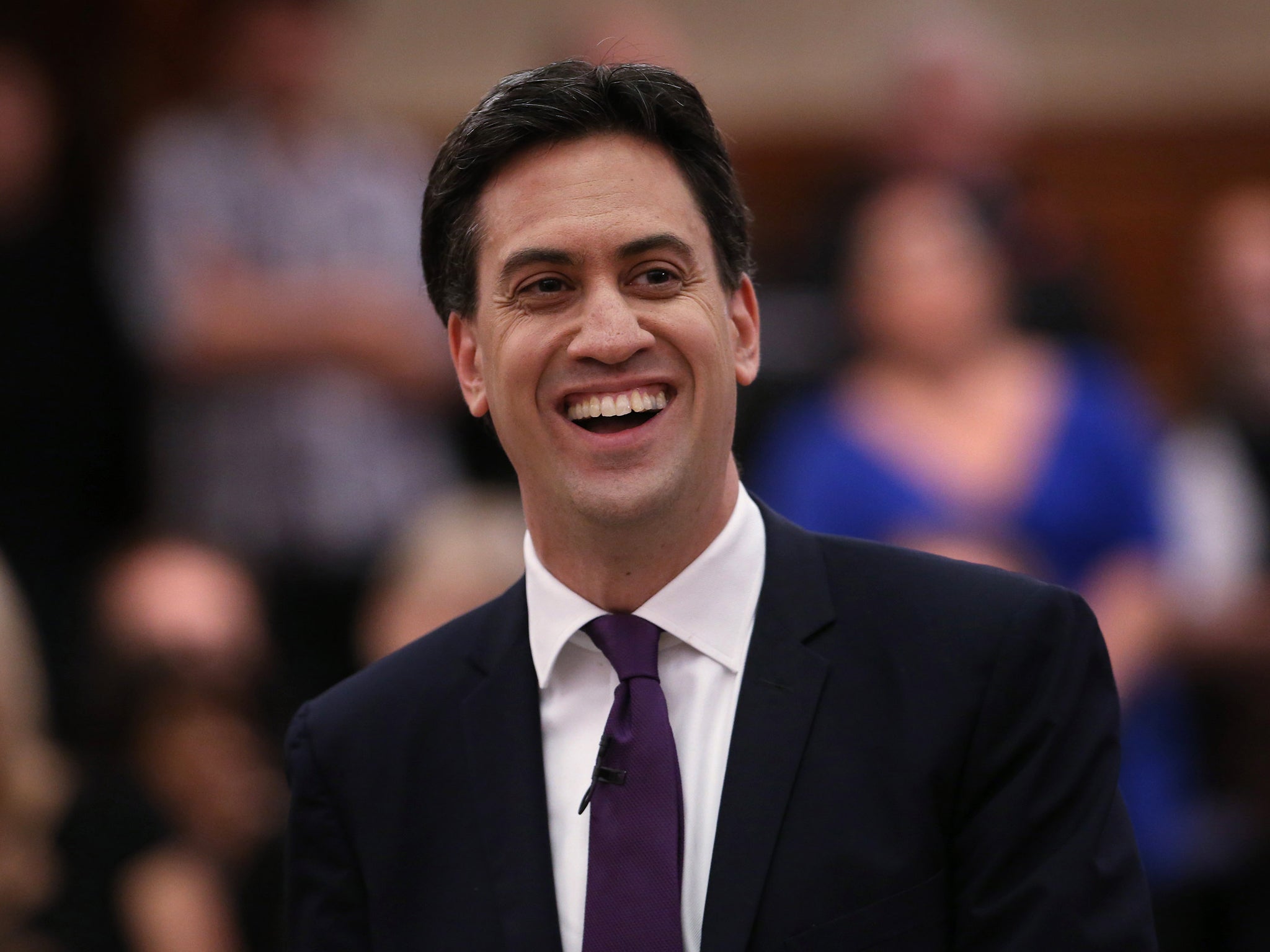

“I see a guy who has been on the backbenches since 1983 – he’s as much a career politician as George Osborne or Ed Miliband. He’s run nothing beyond his constituency office.”

Corbyn, he says, “has to demonstrate that he can manage and lead the great national institution that is the Labour Party. Any support has to be earned”.

New Statesman has changed greatly during Cowley’s seven-year tenure. His re-positioning of the once-imperilled magazine alongside a vibrant website, has extended its audience and restored the “Staggers” to profitability.

He is not about to deviate from his clearly-defined course for the “easy win” of embracing Corbynmania.

“I have got a consistent editorial line and it’s a process rather than a single event,” he said. “It would make us look ridiculous if we suddenly reversed many of our positions.”

It’s a year since New Statesman “broke rank on Ed Miliband”, as the editor puts it. On its cover it depicted Mr Miliband as Doctor Who in a fez, surrounded by former Labour leaders similarly dressed as Timelords. Six months before an election, the headline must have appeared heretical to some Labour loyalists: “Running Out of Time – Is it too late for Ed Miliband to regenerate Labour?”

The accompanying article by Cowley criticised Miliband for being out of touch. “I called him an old-style, Hampstead socialist who doesn’t understand Essex man and woman and I called him a quasi-Marxist – phrases that resonated for months afterwards,” he says.

Cowley was raised in Harlow, Essex, and attended a comprehensive.

The piece led to senior Labour figures seeking to persuade Alan Johnson to lead the party into the election. When Miliband stayed it meant that New Statesman was frozen out during Labour’s election campaign. Cowley was passed the message that “Ed felt personally hurt and let down”.

But he is unrepentant, saying the events demonstrated the title’s influence and that “the Statesman has to occupy another space than being the house journal of the Labour Party”. He adds that the Statesman had “wanted Labour to win” and that it remains a publication “of the left, for the left”. It runs columns from young, left-wing writers including Owen Jones and Laurie Penny.

In his early days as editor he fought hard to counter lingering “perceptions” that the magazine was a voice for either the hard left or the Brownite wing of Labour. He was given the opportunity to reform by new owner Mike Danson (who bought out Brownite Labour MP Geoffrey Robinson).

Danson has given him “complete editorial independence and an excellent editorial budget”. He has also brought the left-wing title into a portfolio of unlikely sister publications that includes World of Fine Wine and Elite Traveller. The Statesman’s turnover is £4.5m and Danson is convinced it can treble that. He would also like to see it have an international edition.

“He’s such a good businessman himself he has made it run as a business,” says the editor.

Cowley’s model for change has been the venerable American title The Atlantic, which has been reborn as a print-digital hybrid and has launched several specialist microsites, including the business-based Quartz. The Statesman has its own microsites; May 2015 was a graphics-filled election site done in partnership with The Independent, City Metric specialises in urban data and social trends, and the pop-culture brand Srsly is set to expand from a podcast into a written format. Cowley’s deputy, Helen Lewis, drives the digital strategy and the website registered 20 million page views last month, a new record.

“The trajectory is only upwards for us,” he says. New Statesman’s circulation is at 33,000 (with 25,000 paid-for at £3.95 a copy), a notable increase from the 23,000 sale he inherited.

The magazine had been in decline since the 1970s and even now it envies the marketing budget of its old, right-wing rival in the periodical market, The Spectator. But Cowley’s strategy has been to create a stable of new writers from George Eaton on politics to Kate Mossman on art and pop culture. The Statesman has built a reputation in detailed analysis of the growing threat of Isis, deploying the likes of Shiraz Maher (a former Hizb-ut-Tahrir member who has been at the forefront of chronicling the activities of Western jihadists) and John Bew. Both work in the war studies department at King’s College, London and contributed essays to a special issue in the wake of the Paris attacks. Through American-style long reads, strong coverage of domestic politics and a revival of the magazine’s original mission as a literary review, Cowley is broadening readership.

“I wanted the Statesman to be read by people who weren’t on the left as well as people interested in progressive politics and the Labour Party,” he says.

This week’s edition contained an homage to “old-fashioned Englishman” Sir Ian Botham, at 60. The Spectator published a piece calling the cricketer and country-sports enthusiast “an arse”.

Cowley – who formerly worked at Guardian Media Group for The Observer – claims The Guardian is limited by an “Oxbridge, liberal, bourgeois mindset”, the kind of outlook shared by Ed Miliband.

“I still live outside of London,” he says. “I have never wanted to be part of that world of Islington and Hampstead, the Guardian dinner-party circuit.”

He maintains that if Labour is to return to political power, the party will have to start winning over the kind of people “who have a different set of expectations and aspirations from the north London liberal intelligentsia”.

But winning votes is not his motivation.

“Above all, I see myself as an independent journalist,” says the New Statesman editor. “And I’ve never been a member of the Labour Party.”

Wading through the climate change spin

The world’s media descends on Paris once more on 30 November to cover another alarming story of critical and global importance.

Days after the Isis attacks, more than 3,000 journalists are expected to report on the 2015 Paris Climate Conference, and it won’t be an easy assignment.

The state of emergency declared by the French government after the 13 November atrocities means there will be none of the usual demonstrations that give a visual sense of the urgency and passion surrounding this issue. The high security will be a distraction from the crucial matter at hand. Journalists must negotiate unprecedented spin from delegates over an issue that’s highly politicised. Scientific jargon becomes a weapon in obfuscation for mealy-mouthed politicians and their PRs.

Maybe it’s time to look at climate change differently? American title The Atlantic has started a newsletter dedicated to the subject, with the less-than-apocalyptic title Not Doomed Yet. Founder Robinson Meyer realised news organisations were trying to make an abstract and slowly-evolving subject conform to the headline-driven rules of the news cycle.

“I saw that a lot of coverage goes straight for the ‘we are 100 per cent doomed’ jugular,” he told the NiemanLab website. “The vein in a lot of mainstream climate coverage is to intone anxiety.”

This subject will be with us all our lives and we desperately need the more considered approach that Meyer is embracing.

A hard-hitting debut from Vice UK’s chief

Chemsex, a feature documentary about a trend in drug-fuelled gay orgies that have been linked to a rise in HIV, is released in cinemas on 4 December. This exploration of a gay subculture is classic Channel 4 territory, but has been made for cinema and online audiences by Vice UK, the British-arm of the New York-based youth media brand. The film examines a craze for weekend-long sex parties, sustained by disinhibiting drugs such as crystal meth.

Rebecca Nicholson has made the film the hub of her first commission as editor-in-chief of Vice UK. She said the film, supported by a “Chemsex Week” of related editorial, would mean the scene was not dismissed as a “faceless problem”. She said: “There are parts of the story that will be familiar to many young people: how to cope when partying goes too far; how to find love and sex in the digital age, when apps are commodifying romance; and where to turn when it all gets too much.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments