National lampoon: 50 years of Private Eye's ingenious political cartooning

From scabrous caricatures to full-scale skewerings of society, a new book looks back on the satirical publication's ingenious cartoons...

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There's a type of telephone call that every political cartoonist dreads. It's the one from an MP – or more likely from their office minion at Westminster – asking the price of a drawing that was intended to cause hurt but will instead end up on the subject's toilet wall as a trophy to feed their sense of self-importance.

It is, perhaps, an explanation for why the art in Private Eye, Britain's most-successful satirical publication of the past half-century, has changed so much in that time.

Fifty years ago, the cartoonists at Private Eye were scabrous. They would sketch their jokes with the scent of a minister's blood in their nostrils, seeking to inject venom into every line of the drawing. Their targets were clearly identifiable members of Britain's ruling class and there was a belief that the cartoon, as a medium, was capable of inflicting genuine pain.

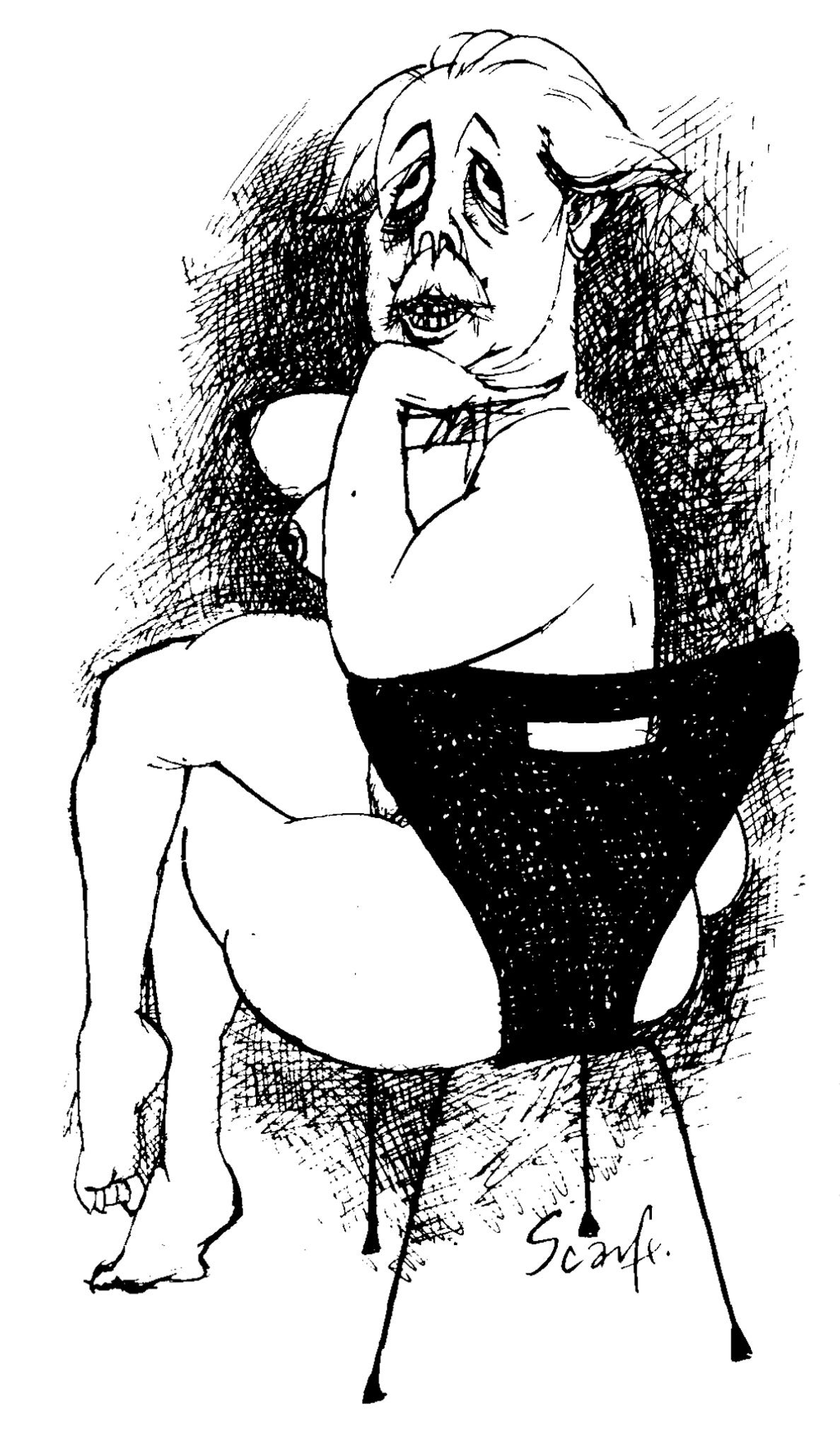

Gerald Scarfe made his name there, depicting Harold Macmillan posing naked in 1963, his wobbly flesh spilling out in all directions from the Arne Jacobsen chair associated with the Profumo Affair model Christine Keeler. He later drew Harold Wilson kneeling behind Lyndon B Johnson in support of the Vietnam War, pulling down the president's trousers as the American leader tells him: "I've heard of a special relationship, but this is ridiculous." So near the knuckle was this cartoon that editor Richard Ingrams made Scarfe draw in a pair of underpants to cover the presidential buttocks.

It is a reflection of modern politics that the Eye today sees Westminster life in terms of the children's comic. Dave Snooty and his Pals – a parody of the Beano strip Lord Snooty and his Pals, is the creation of Private Eye editor Ian Hislop and his close friend Nick Newman, one of the magazine's great cartoon stalwarts of the past 30 years. The strip mocks the Education Secretary as Michael "Oiky" Gove and shows the Prime Minister repeatedly thwarted by his nemesis in a red-and-black striped jumper – Boris the Menace. "When Cameron arrived he reminded us of Lord Snooty and we thought 'How much more childish can politics get?'," explains Newman.

He has now compiled Private Eye: A Cartoon History, a record of how the magazine has illustrated Britain in strips and stand-alone gags since it was founded in 1961.

He acknowledges the cartoonist's sense of irritation when an MP claims to enjoy a joke, and asks for the original. "They are so thick-skinned, it's frustrating. You want to wound but it's really hard to do so. I don't think it's our failure so much as that they are just fantastically vain. They are happy to be pilloried in any which way so long as they are getting publicity." Jeffrey Archer is the biggest offender, apparently. "Maybe he just buys them to destroy them?"

The tradition of the scabrous political cartoon is now left largely to the national newspapers. Private Eye instead will try to puncture a minister's standing through its written articles and all-important cover. As veteran Eye artist Barry Fantoni points out: "We realised that putting a bubble into a photograph had an immediacy."

The magazine decided that its drawn cartoons now needed to do something different and the result is that society as a whole became the butt of its jokes. Divided into decades, Newman's collection gives a remarkably clear record of the country's changing values, its hypocrisies and absurd obsessions, demonstrating the power of the cartoon as a social document.

Whereas other media are often content with depicting the 1960s as an era of liberation and fun, for example, the humour of the Eye cartoonists ensured a darker reality did not go unnoticed. Thus, in a minutely detailed sketch of Swinging London, titled "Britain Gets Wythe Itte, 1963", Timothy Birdsall satirises the sleaze of "girlie" magazines, the scandalmongering and hate of the tabloid press, the greed of the legal profession and fledgling advertising sector, homophobic reactionaries carrying aloft placards stating "Hang all the queers." And, gazing down from Nelson's Column, Macmillan implores the masses to "Looke around ye, my people! See what happinesse Ie have brought ye!"

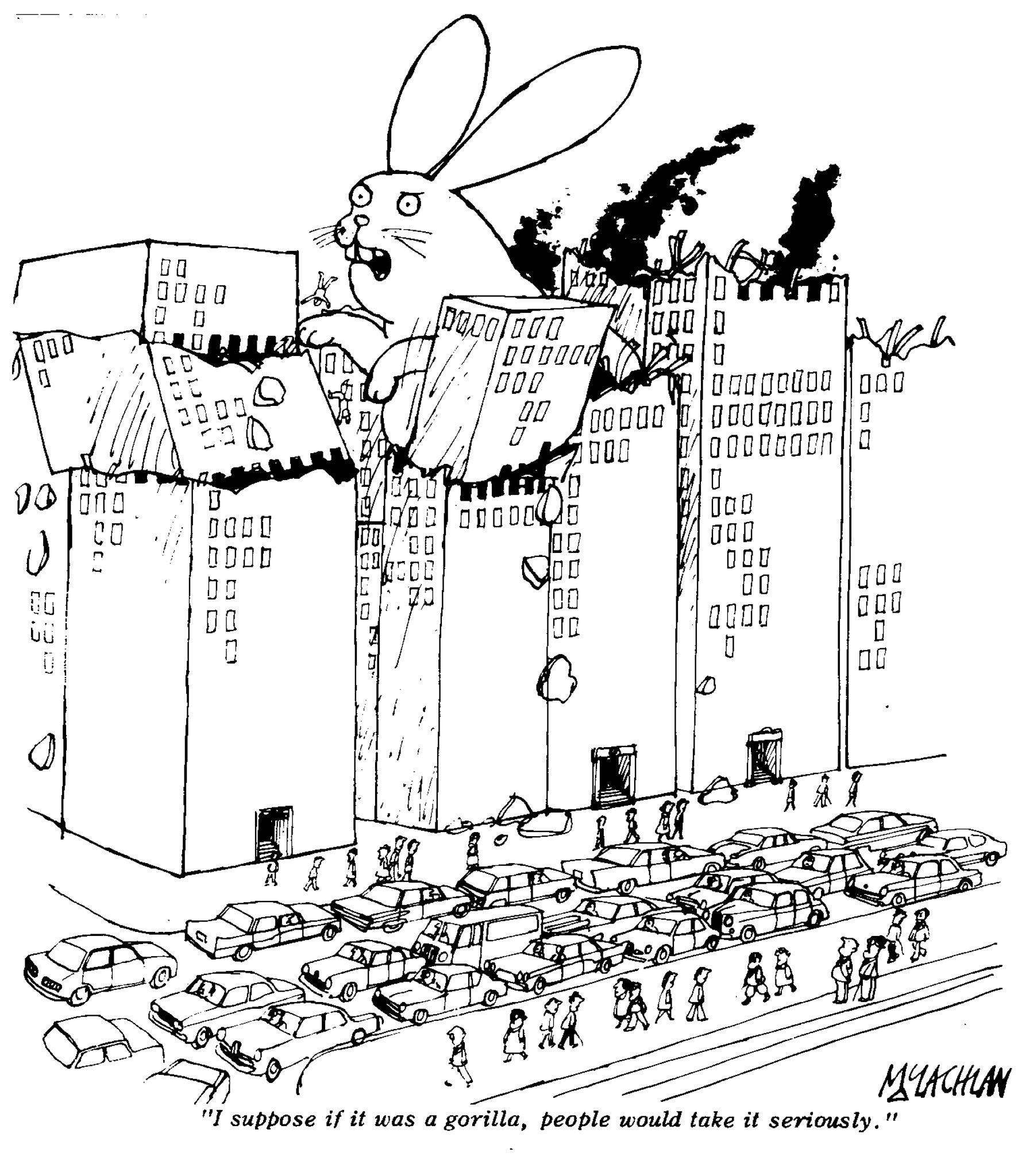

By the 1970s, that strange decade of Cold War paranoia and glam rock, the Eye's artwork had become "more surreal", says Newman. The approach was typified by Ed McLachlan, who drew a giant rabbit raging through the streets of Manhattan as a passer-by comments: "I suppose if it was a gorilla, people would take it seriously."

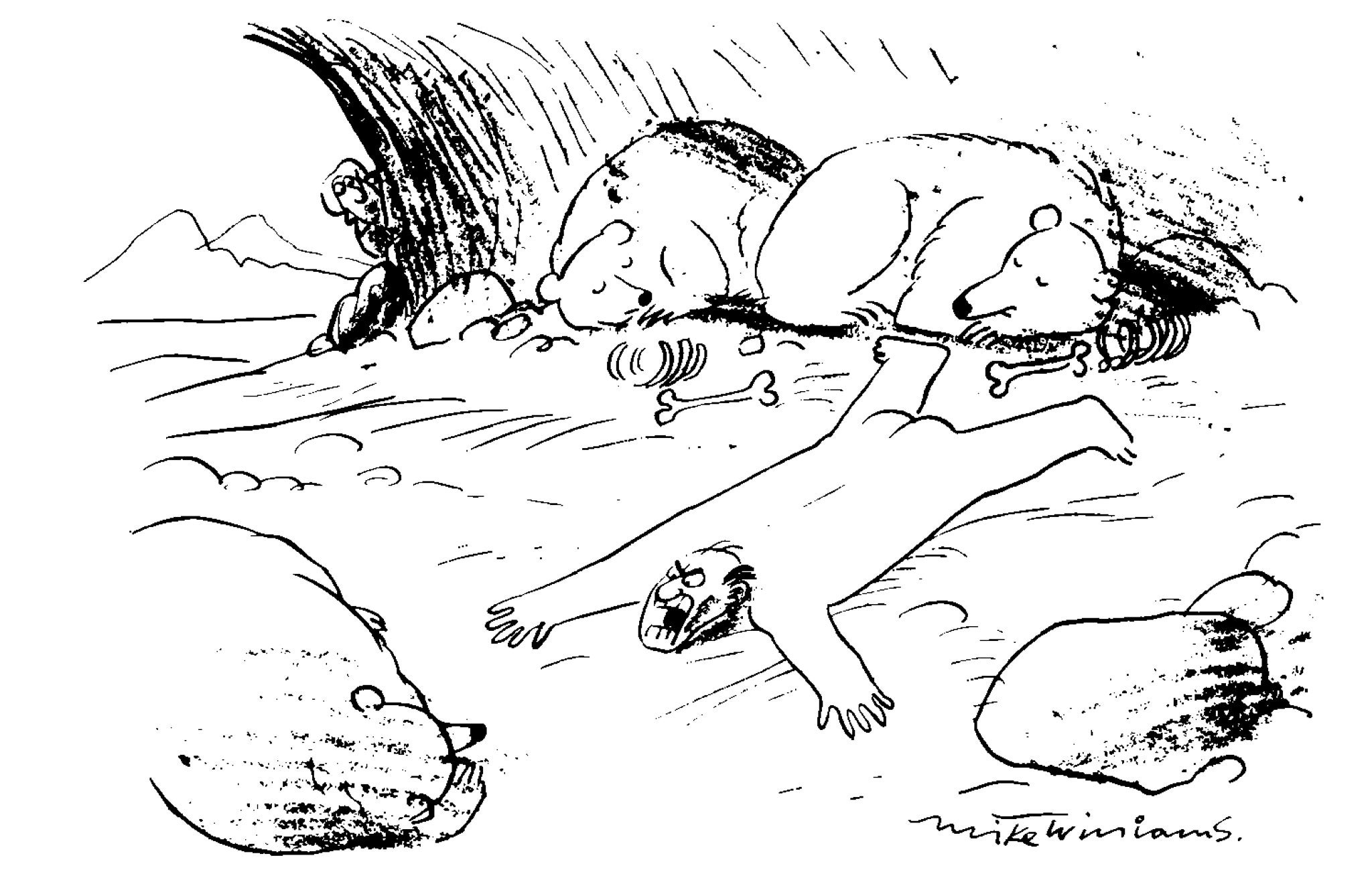

Cartoon themes peculiar to the 1980s included kissograms and names printed on windscreen sun visors – though the Eye cartoons of this decade were also affected by the misfortunes of a rival publication. The demise of Punch allowed the Eye to publish the work of cartoonists such as Mike Williams, who specialised in classic themes such as the "reverse joke" of a human rug on the floor of a bear cave. For most cartoonists, the enduring subjects (man on a desert island, man on a window ledge, lemmings going over a cliff) are an irresistible challenge.

"If you can get a desert-island joke away, there's a great sense of achievement," says Newman. "Of course you are trying to amuse the readers but the people you are really trying to make laugh are your fellow cartoonists. If somebody says they like your lemming joke, you think you've made it."

Between the 1970s and 1990s, the Eye's political cartooning was led by John Kent and his elegantly drawn strips. Michael Foot was the subject of "Worzel Gummidge", (reflecting the Labour leader's supposed resemblance to the scarecrow), and the perilous administration of John Major (whose father worked in the circus) was captured in "John Major's Big Top". But Kent attracted most admirers for his drawings of Margaret Thatcher in strips such as "Maggie Rules OK".

"So many cartoonists have copied John Kent because he could get a likeness in a few [pen] lines," says Newman. "Margaret Thatcher was actually an incredibly difficult person to get right. When Ian [Hislop] and I were working on [television puppet satire] Spitting Image, they struggled the whole time to get Maggie right. [The show's co- creator] Roger Law said it was because she was quite a good- looking woman, and that they had the same problem with Diana."

Newman and Hislop were among those inspired by Kent as they introduced new political strips. Comics invariably provided the blueprint. "Dan Dire", for example, was based on Dan Dare and with Thatcher as a Mekon alien, Labour's Neil Kinnock floating in space and the Social Democrat Dr Owen as Dr Whoen, the Waste of Time Lord. More recently, "The Adventures of Mr Milibean" – lampooning Ed Miliband and based on a TV cartoon of the hapless Rowan Atkinson character Mr Bean – is drawn by the former Beano and Dandy artist Henry Davies.

In the past 20 years, the Eye has developed some recurring cartoon themes of its own – usually linked to a catchphrase ("Are you looking at my bird?" is one, "Does my bum look big in this?" is another). But bizarrely, the catchphrase which attracts the most competition among cartoonists as to who can use it most innovatively is, "Hi honey, I'm home," according to Newman. "It's the stock line from 1950s American sitcoms. I've no idea why it took off, but it became a challenge for cartoonists to come up with an original version of such a cheesy, corny line and turn it into something funny."

Another theme that has recurred through most of the past five decades is the miserable nature of most cartoonists, best exemplified by the famously gloomy – and brilliantly funny observationalist – Michael Heath. It's probably why the man on the window ledge is such a popular topic. "There are a lot of people topping themselves in Eye cartoons," says Newman. "We work in a vacuum and it can be a very solitary profession."

With relatively few outlets for cartoonists now, there's fear about where the next generation will come from. "When I started off, people in their teens and twenties were trying to get into the Eye and Punch, but now there aren't that many young cartoonists around, unfortunately. I wonder if it's because they think they can hit a million people on a YouTube mash-up," Newman speculates.

It takes a collection such as this to make you realise what we'd be missing. Cartooning is a complex tradition of British publishing that goes back to the 18th century. It can be whimsical but also melancholy and still, occasionally, vicious. Of course, first of all it should be funny – but it's about a lot more than just making us laugh. And at its best, it is revelatory.

'Private Eye: A Cartoon History' is published by Private Eye, priced £25

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments