Stephen Glover: The future of the free press will rest on Murdoch making us pay

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a way, one can't blame Gordon Brown for saying that paywalls won't work.

In fact, to be precise, he seemed to be saying that they shouldn't work. In an interview last week with the Radio Times, the Prime Minister opined that "people have got used to getting content without having to pay", before adding: "There's a whole sort of element of communication that's got to be free." The first part of what he says is true, the second highly contentious.

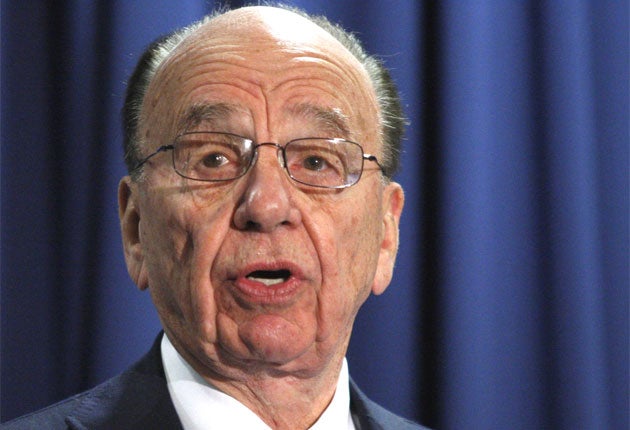

Most people have interpreted his remarks in the context of his deteriorating relations with Rupert Murdoch's The Sun which, having supported New Labour for many years, has turned on the party and Mr Brown with ferocity. Mr Murdoch has, of course, recently announced that, from June, online readers of The Times and Sunday Times will have to pay £1 a day or £2 a week. The Sun and the News of the World will follow later.

I don't at all mind Mr Brown having a pop at Mr Murdoch. The Sun has been very beastly to him. My difficulty is that the Prime Minister's comments undermine the whole newspaper industry. Just because readers have got used to reading papers online for free, it does not follow that they have acquired a right to do so until the end of time.

Gathering news costs money, sometimes a great deal of it. Mr Brown presumably does not expect Marks & Spencer to give away its clothes and food, so I'm not therefore sure why he thinks newspapers should give away their journalism.

What depresses me about this debate is that Mr Murdoch's critics – some of whom may be moved by atavistic political hatreds – have come up with no alternatives which have any chance of saving newspapers. They merely say that the online advertising model must be made to work without telling us how this miracle will happen.

The basic facts are these. As newspapers shed paying customers to the non-paying internet, they lose revenue, and are less able to support costly journalism. The longer the process goes on, the worse it will become. One can reasonably wonder whether Mr Murdoch's plan will work – whether enough people will pay for The Times and Sunday Times online when there are so many rivals continuing to offer their content for nothing – but surely one cannot reasonably dispute his right to try.

And what if he fails, as so many are predicting he will, invariably pronouncing that "Rupert does not understand the internet"? No one has come up with a Plan B. Maybe there isn't one. What then? Well, newspapers will continue to weaken until, in the end, no one apart from philanthropists and governments will be able to afford to publish them.

That is why all of us – including you, dear reader, who understandably does not want to pay – must hope that the 79-year-old tycoon succeeds.

Most media folk seem convinced he won't, and I must say my own inclinations lie in that direction. But I think all of us, the Prime Minister included, should be a little more humble.

Mr Murdoch is the most successful publisher of modern times, arguably of all times. Maybe he is growing a touch senile. Maybe he doesn't understand the internet. Yet he is still Rupert Murdoch, and his is the only game in town.

I for one am glad he is trying, and whoever questions his right to do so does not care for the future of a free press.

Newspaper executives are acting like fat cat bankers

Newspapers have been inveighing against "fat cat" bankers for continuing to pay themselves astronomical salaries in these straightened times. Yet there are executives in our troubled industry who are no more sensitive to the prevailing mood.

Last week it emerged that David Montgomery, the chief executive of the European newspaper group Mecom, was paid £874,000 in his total remuneration package in 2009, an increase of 51 per cent compared with the previous year. And yet Mecom posted a 28 per cent fall in profits in a year in which the company laid off 850 staff, roughly 10 per cent of the workforce.

The lay-offs provide a clue. Mr Montgomery is an expert at cutting costs. It is his chief – some would say his only – attribute as a newspaper executive. The company reduced operating costs by €140m (£123m), and much of the credit must go to Mr Montgomery – hence his increased package. But is cost-cutting reason enough to pay someone more money, particularly when profits fall?

A similar picture emerged recently at Trinity Mirror. Its chief executive Sly Bailey received a total remuneration package of £1.68m in 2009, an increase of 66 per cent compared with the previous year. And yet in 2009 Trinity Mirror reported a 41 per cent fall in pre-tax profits while sacking 1,700 people and closing or selling 30 titles. Like Mr Montgomery, Ms Bailey seems to have been rewarded principally for getting rid of people.

If a newspaper group increases profits, particularly during tough times, its most senior executives should receive significant rises. But when profits fall? The Daily Mirror would scream if a banker's salary soared as profits dropped, but its own Sly Bailey is judged in another light. Why are newspaper executives different? As the Daily Mail might say: "They still just don't get it, do they?"

A fine writer does not deteriorate with age

The best article I read about the death of the Polish President in an air crash was by Neal Ascherson in The Observer. Mr Ascherson is an authority on Poland, having written about it for many years, and one would have expected him to have produced an outstanding piece. But that led me to another thought. Why doesn't he have a regular column?

Mr Ascherson was "let go" by the Independent on Sunday 12 years ago as a mere toddler of 65. Around the same time, the no-less brilliant Peregrine Worsthorne was despatched by the Sunday Telegraph at the tender age of 74. Both men have continued to dazzle in various places, but no editor has had the good sense to offer either of them a regular column.

Newspapers are weighed down with columnists. There are some who cannot write very well, others who do not know very much, and one or two who fall into both categories. And yet two beautiful writers (and there are others) brimming with thoughts and experience are ruled out, apparently on grounds of age. Sounds like discrimination.

scmgox@aol.com

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments