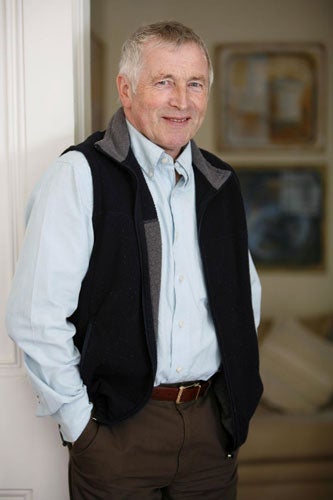

Jonathan the great: The younger Dimbleby on his toughest journey

The legendary broadcaster's series on the world's largest country was an intensely personal odyssey, as well as his toughest professional mission. Now back home and abundantly happy with his young wife and baby daughter, he talks to Ian Burrell

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

According to the opening lines of Anna Karenina, "all happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way."

Jonathan Dimbleby took a dog-eared, paperback copy of Leo Tolstoy's great tale, considered by some to be the greatest novel ever written, on his recent odyssey across Russia, re-reading the work on a train out of Moscow crowded with migrant workers. One Ukrainian, slightly the worse for wear through drink, urged his British travelling companion to share his bottle of beer and praised his choice of reading matter with the words, "great man, great writer". The television presenter, best known for heavyweight political programme-making, smiled at his new friend, chatted through his interpreter and took a hearty swig.

Dimbleby has a renewed sense of joie de vivre. Effervescent, with a wide-eyed enthusiasm, he finds himself – in a way he would have once found hard to imagine – living blissfully within the first of Tolstoy's two categories of domestic life: the happy family.

As he sits in the living room of his north London home, his young wife, Jessica, brings a plate of walnut biscuits. "You are nice," says her husband. "Walnut biscuits? Woo-ah, they're all going to be gone." At his feet are strewn children's toys belonging to the couple's baby daughter, Daisy. Intermittently during the interview, the presenter, who once interrogated politicians on shows such as On the Record, leaps up to catch a glimpse of his offspring and rushes to engage her in baby talk. "I need to have my fix," says Dimbleby, who at 63 is the goofiest of goofy dads and clearly very comfortable with that.

This new-found contentment reveals itself throughout the great adventure that is Russia: A Journey with Jonathan Dimbleby, an epic BBC2 series that has spawned a hefty accompanying book. In the introduction to the latter, Dimbleby, the son of the great BBC correspondent Richard, and the younger brother of Question Time's David, devotes two pages to an extraordinarily candid account of the harrowing personal journey he underwent during the three years that preceded this great journalistic assignment. His attempts to wrestle with the identity of the Russian bear coincided with his efforts to find himself, during what he describes as "a roller-coaster period in my personal life".

Dimbleby informs his readers of the love affair he had with the opera singer Susan Chilcott, her subsequent death from breast cancer and, as he mourned, the break up of his long-standing marriage to the writer and journalist Bel Mooney, with whom he has two children.

"For day after day I could barely bring myself to get out of bed in the morning. Nor did I care whether I lived or died."

He tells of meeting Jessica in 2004 and his return to "mental equilibrium", admitting "I was still frequently stricken by waves of grief that welled up unexpectedly, drowning out every other sensation". Those "sharply fluctuating moods" surfaced during the trip that took him across six time zones and stretched from Murmansk to Vladivostok.

"My journey through Russia played what, in retrospect, I believe to have been a crucial part of my recovery – a parallel journey," he writes.

Back in London, he appears aware that the candour of his Russian work has added a new dimension to his broadcasting oeuvre, a body of work that includes landmark pieces such as Charles: the Private Man, the Public Role, on the life of the Prince of Wales; The Last Governor, on the end of British colonial rule in Hong Kong, which also became a book, and innumerable films for such prestigious documentary strands as This Week and First Tuesday.

"Russia was a very daunting project," he says. "Over the years, I've reported from all sorts of dramas and crises around the world, from more than 80 countries, and made big scale series, but this was by far and away the most challenging." Not only was he attempting to get beneath the skin of Russia, he was doing so "as a traveller on a quasi-personal journey".

So the BBC2 series showed a beaming Dimbleby horse-riding in the Caucasus, indulging in vodka-fused tenpin bowling in the Volga city of Samara, receiving a rubdown in a Moscow banya and diving, in his underpants, into a sulphur pool in Pyatigorsk. In describing such experiences, the word he frequently returns to is "liberation".

"It was tremendously liberating. I enjoyed the totally casual moments getting on a train and thinking, I can smell food and human bodies here, I will turn round the camera and say it. If it works it's totally spontaneous, it's real and it's genuine and I like to think it can be illuminating as well," he says.

"You slide and slip into a sulphur bath in your underpants and no one takes any notice at all. Some people are natural born killers, I'm a natural born show off, I just decided, in for a penny in for a pound, don't be self-important, don't be self-conscious, go for it. I can't think of anywhere I have been where people have been less curious about the camera and less inclined to give it two fingers."

Though he may have cast off inhibitions, Dimbleby is not engaged in reinventing himself to reflect the modern vogue for celebrity presentation. Indeed, he was praised by a reviewer from The Daily Telegraph for his willingness to "take second place to [his] material".

"It would be bizarrely arrogant to say that I was more important than Russia," he say. "I'm not lacking in self importance, but with the benefit of hindsight I think this kind of series can only work if you create an atmosphere where people talk freely to you, if you don't mind making a fool of yourself, throw yourself in at the deep end and ask pertinent questions. What one writes in commentary is very important as well."

Although this was a personal journey, Dimbleby admits to occasionally having the pioneering TV traveller Michael Palin at the back of his mind and to hearing the tone of his brother, David, in some of his own utterances. His style will always be partly informed by the lessons he learnt from his father. "He always said you are annotating television commentary, you are not repeating the visually blindingly obvious. You are adding to the image that you are showing someone for the first time, but that you've seen again and again in the cutting room."

Meeting viewers at book signings has helped him to realise how fortunate he was to have undertaken this vast trip and to have met such a range of people; the Cossacks, the gangsters, the women working in the fields, the white witches and the intellectuals. It wasn't as easy as it looks, he says. "Russians don't have the easy smile that we Westerners use, they look at you blankly, sometimes with apparent hostility. You have to be friendly and direct, there's no room for smooth talk. Once you get below that veneer and understand why Russians are so often fatalistic, you find a warmth and humanity and generosity which matches anywhere else in the world."

Even so, he is not about to be commissioned by a Putin-era Pravda, having no time for the current regime, though he acknowledges the prime minister's standing with the Russian people. "My overwhelming feeling about Russia is that it's not a happy place. It's resigned. The people have been beaten for so long. But because Russia is standing tall in the world, thanks to oil, Putin is regarded by most Russians as the nation's saviour, which is quite dispiriting."

In the course of making the series of five hour-long documentaries with executive producer George Carey, who had the original idea, Dimbleby visited the site of the Beslan massacre and in St Petersburg met an old man with whom he discussed how watches were sold for horse fodder during the siege of what was then Leningrad.

Though he is aware of the sometimes perilous conditions faced by Russian journalists, he says he never felt under threat himself. "For a foreign journalist there's no discernible risk. We had permission from the FSB (Russia's Federal Security Service), they knew where we were going and were perfectly aware. The security services are all powerful and extremely clever. When small fry like me are going through, they know exactly what you are doing."

He was eventually granted permission to film in the war-ravaged state of Chechnya, but decided the integrity of such a journalistic exercise would be compromised. "The circumstances would have made it impossible, we would have been surrounded by security."

In taking his Russian assignment, Dimbleby had to make a sacrifice, namely giving up his political show on ITV, Jonathan Dimbleby on Sunday. "That was a big decision because I enjoyed that programme. I had been doing it for more than a decade and it's a wonderful perch on the inside of politics, and I still miss the live political interview."

Due to his long history of political programme-making for ITV, he is genuinely hurt that the broadcaster appears to have given up on such material. "If it's permanent I think it's very disappointing, and I also think it's missing a major trick, there's a real appetite now for the discussion and forensic examination of politicians on big issues," he says. "What's the real cost of living? How many people are coming in and out of this country? How are we going to cope with food prices? Ditto oil. How are people going to be re-engaged with the political process? These are huge issues facing a very troubled country. I still believe ITV is the people's channel and these discussions should be there. I find it really dismaying that it appears to have gone."

But, enough of the worrying, Jonathan Dimbleby, who continues his 20-year role as chair of Radio 4's Any Questions?, is happy once again inside his own skin. Friends who watched his recent television work remarked on the authenticity of his presentation. "The great delight of this was that I could simply be myself, for better or for worse, and friends who know me say, 'Jon, that's you!'"

And in the wider broadcasting industry he feels that, having been to Vladivostok and back, he really has nothing more to prove. "My peers know who I am professionally. I feel I've climbed quite a lot of mountains, and I still like climbing mountains but I'm not scrabbling on the edge of the precipice and saying, 'I've got to get to the top of this one.' I'm slightly at the 'take me or leave me' stage. It may mean that they leave me, but I can survive that," he says. "There's nowhere up the greasy pole or the ladder that I particularly want to go."

And with that, we must leave him to get his fix with Daisy.

'Russia: A Journey with Jonathan Dimbleby' is now available on DVD, priced £24.99. The accompanying book, 'Russia: A Journey to the Heart of a Land and its People', is published by BBC Books, £25

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments