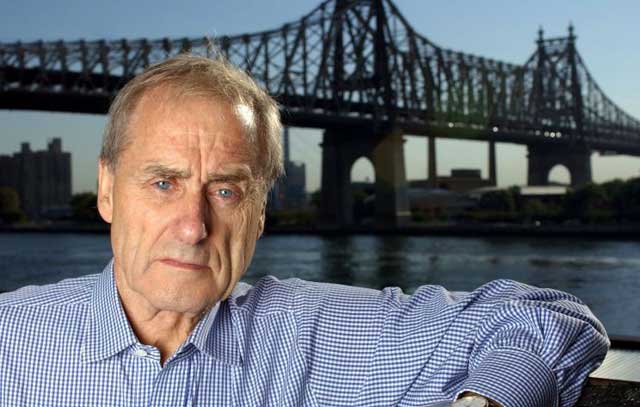

Harold Evans: 'These grand designs must have stories to back them up'

Harold Evans is one of journalism's great innovators. He tells Joy Lo Dico why style and content are mutually indispensable

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is 35 years since Sir Harold Evans published Editing and Design. In its day, the five volumes on the art of editing, typography and layout was regarded as something between a manual and a bible for Fleet Street. It's a little harder to find these days. "You can still get it on Amazon," Evans eagerly informs me from his office in New York.

The newspaper industry has come along way since 1973. One could not expect even the visionary Sunday Times editor to foresee the convulsions of Wapping, the computerisation of the newspaper industry, the quality compact (though he did spot the smaller format El Pais as a trend-setter) and the impact of the internet. "Here's a thing about innovation," says Evans sagely. "Nobody has ever predicted the next innovation." In one respect though he did clearly lay claim to having seen the future: that design would have to take the lead. "Newspaper design cannot go on being so insular if the newspaper is to fulfil its role," he wrote in Editing and Design.

His secretary Cindy is warding off calls so that he can get on tapping away at his memoir, Paperchase, but the opportunity to talk newspaper design won't pass Evans by. "It is way ahead of what was possible or creatively desirable 20 or 30 years ago," he says. "I don't want to be in a position of criticising modern design. I think it's wonderful. But I do utter these cautions: don't dismiss the classic news photograph in black and white; don't exaggerate the use of colour; and do think, as well as the visual appearance, 'What the hell is it saying?' Why are newspapers losing circulation?" The answer to his question is of course content.

New typography and layout won't reverse the downward trend in newspapers but Evans cautiously supposes that it could at least "sustain" them.

The last five years have seen British newsstands heaving with redesigns. In response to The Independent and The Times going "compact" in 2004, The Guardian overhauled itself in 2005 with a new Berliner format. The Observer followed suit shortly afterwards. The Times had a revamp in 2006 with input from Neville Brody, former art director of The Face and a further update in May from its new editor James Harding, including advancing leaders to page 2 (Evans toyed with putting leaders on page 2 and 3 in 1981 when he was briefly editor of The Times, but decided against). Two weeks ago, it was the turn of The Sunday Times which brought in new typefaces, prominent news graphics and panel insets and a technicolour front page.

The spur for much of the change has been the availability of the full-colour presses. Once the preserve of magazines, colour now strides across the pages of broadsheets, in mastheads, section tags, panels, and most noticeably in quick-cropped vibrant photographs on every page.

"Colour is a sword and a dangerous weapon at the same time," says Evans, who worked with it extensively first on The Sunday Times Magazine, and then when he founded Condé Nast Traveller. "The page may be seen more as a palette than a page by some people but designers I worked with, such as Michael Rand and Edwin Taylor, did recognise that the most effective combination was black and white text maybe with black and white photographs and then colour when it added to it. I do dislike the fruit salad effect if it's scattered all about."

He also bemoans the lack of quality reportage photography. "Many photographs are still better in black and white," he says. "This is not just an aesthetic judgment of mine. It's a way a photograph communicates and a photograph, because it is in colour with confetti, is not superior to a black and white image."

Querying the dominance of colour photography in modern newspapers seems a little like Robert Oppenheimer disowning the atomic bomb. When Evans edited The Times, a brief tenure from 1981 to 1982 before a falling out with Rupert Murdoch, he led something of a coup. The occasion was the wedding of Lady Diana Spencer to Prince Charles. In a carefully-planned operation, his photographer Peter Trievnor got the decisive shot at 12.10pm. The transparencies were flown to the East Midlands to be pre-printed on colour reels and arrived back to London at 10.18pm, just in time for the next day's edition. It was the first colour photograph in a national broadsheet.

During Evans's reign at The Sunday Times from 1967 until 1981 it gained a reputation as the world's best newspaper. That owed much to robust journalism: the investigations of the Insight team, the campaign for compensation for child victims of thalidomide, uncovering Kim Philby's role as a Soviet spy and the publication of the controversial diaries of the former Labour minister Richard Crossman.

What he also brought was a visual flair to the newspaper. The Sunday Times Magazine, which he inherited from his predecessor Sir Denis Hamilton, became a showcase for the photography of the quality of Don McCullin's. Evans also brought his art director Edwin Taylor into a central role and promoted the news graphic, then its infancy, into an art form through the work of Peter Sullivan.

The news graphic has seen a resurgence in the recent redesigns, in particular at The Sunday Times. Al Travino, the art director at News International, may have produced a 21st-century newspaper but he still tips his hat to predecessors who led the way under Evans. "It (the relaunch) was trying to rescue some of the innovative visual journalism brought to the paper years ago by pioneers such as Peter Sullivan and Edwin Taylor who made it a very influential, content-driven newspaper," said Travino in an interview with Garcia Media.

While The Sunday Times is referencing back, Evans himself cannot be accused of being a regressive. His admiration for technological advance is evident in his book on the great US innovators: They Made America. One place that doesn't reach is the US newspaper. Evans, who has just turned 80 and has been living Stateside with his wife Tina Brown for 25 years, still turns to British newspapers for superior and innovative design.

He is full of praise for The Sunday Times, The Independent and The Guardian. He has begun to have hopes for The Wall Street Journal, acquired controversially by Rupert Murdoch at the end of last year. It began its move to modernity in 2007 by trimming three inches of its width dropping a column from the front page. More can be expected in the next few months. "The Wall Street Journal has, in the last two or three months since Murdoch took it over, been dramatically improved. They've got rid of the Cheltenham mountainous face, that is still in The [New York] Times. The Wall Street Journal has gone for a simpler Bodoni - it might be a slightly different name now but it has gone for that. They've made the mistake of still continuing the upper capitalisation but the whole Journal is well-designed – a major improvement in my opinion."

Though he admires his hometown newspaper The New York Times for its content, he regards it with huge frustration. "Should The New York Times be redesigned? Absolutely," he says. "To give you one simple example of newspaper design. If you have one very attentive ear, you can hear rows in New York as people try to follow a section jump, from the first section to C section. If your wife or husband is already reading the C section and you have a jump, it's impossible. The New York Times desperately needs to rethink its whole design."

The New York Times may have held up changes for fear of upsetting its conservative readership but do things lose their authority by bowing to the seductions of colour and design? "No," says Evans. "The same argument is used when the [British-based] Times put news on the front page, the same argument was used against me when I put information on the back page. It's bullshit. What does the authority consist of? Does it consist of a small type and slovenly presentation and classified advertising? No. It consists of the clear visual signal and how you organise the values on the page. The most important thing is: 'Is it giving me a calibration of news values?' You don't lose authority by organising things clearly. You actually lose authority by presenting things in a way that appears [as though] you haven't thought about the space."

Even the internet, which makes many old newspaperman quake, is an opportunity. The web and mobile phones may offer the cheap "bang, bang" news hits, but he can see the relationship go both ways. When talking of The Sunday Times, he likens its vivacity to a well-designed website. The methods of the internet become a design leader.

"If you go on a website and click on something you will go from four lines or a boxed panel to a whole page in itself. The explosion effect. You click on a small video and get the whole video. For the story The New York Times was going to jump [sections] – on the web you just click. The web has obviously speeded everybody up. Of course, that is a fantastic facility and it ought to remind people in different places where they are not doing it that there is more than one way to skin this cat."

However, for all the glitz of it, Evans is still adamant about what is required to make a great newspaper. "Bear in mind my wife edited The New Yorker. Even today The New Yorker is hugely read, more than a million circulation and some very, very long reads. There's a series of complications here. Design can't be considered without the context, the information. Design is absolutely no substitute for content."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments