Andrew Keen on New Media: Google's tenth birthday present to itself – the age of Chrome is here

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A decade ago yesterday (7 September, 1998), a new company called Google was incorporated in Menlo Park, California. Google's 10th birthday has an ironic mathematical resonance. Google was named by its two young Stanford University electrical engineering graduate students in misspelt homage to the word "googol" – an infinity-like number denoting 10 to the power of 100 (that's the number one followed by a hundred zeros).

But the irony is that, in its first 10 years, Google has achieved googel-like growth, ratcheting up the ones and zeros faster than any other company in the history of global capitalism.

The company has gone from a start-up with zero revenue to the best-known brand in the world with almost 20,000 employees, a market cap of around $150bn, annual income in 2007 of $16bn and a truly ubiquitous search-engine which indexes tens of billions of web pages, serves billions of daily requests and fields 66 per cent of all web searches. This pre-adolescent Silicon Valley company has become both the lead actor and the most complex metaphor of our digital age.

So what's next for Google? Like a child genius, has the company peaked early? Will its teenage years be anti-climactic? Where will Google celebrate its 20th birthday?

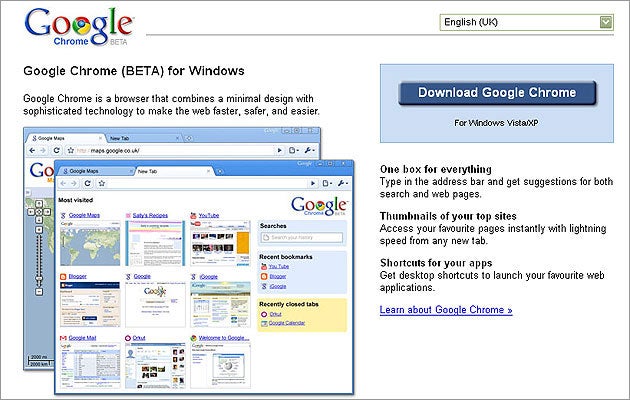

One clue to the future of Google lies in the release last week of a beta version of Chrome, its new open-source web-browser. On a prosaic level, Chrome is a classically minimalist Google product – a fast, stripped-down alternative to Firefox, Safari and Microsoft Explorer, which offers a number of new browser features such as a wickedly intuitive new search bar, significant improvements for storing web information and downloading rich-media files as well as major upgrades to online security.

Currently, only available on Windows XP and Vista, I'd advise all internet users – particularly the 75 per cent of internet users who, for one reason or another, are currently stuck with the pedestrian Windows Internet Explorer – to at least download Chrome from www.google.com/chrome and give Google's 10th birthday present to itself a test drive.

But, on a deeper, googel-like level, Chrome symbolises the future – both of Google, the internet and the wider technology industry. It is perhaps no coincidence that Chrome was released on Google's 10th birthday. The browser is an augury of the coming grand synthesis of old fashioned desk-top computing and the new world of always-on internet computing.

Chrome enables users to run applications which have traditionally relied on local personal computers. It is, therefore, a web-browser which is simultaneously an operating system.

As Google co-founder Sergey Brin said at the Chrome's press launch: "I think operating systems are kind of an old way to think of the world. They have become kind of bulky, they to have to do lots and lots of different (legacy) things."

In the long run (say, in another 10 years), Chrome will probably make traditional operating systems redundant, thereby consigning Microsoft, Google's only real rival, to the dustbin of business history.

In Silicon Valley, this next great revolution is called "cloud computing" and it signifies the migration of all information-technology to the web-browser, where everything will become a "service" distributed from the internet. In 10 years time, therefore, my guess is that Google will, both literally and metaphorically, celebrate its 20th birthday in the clouds. By 7 September, 2018, Google might not quite be like a god – but if it forces the demise of Microsoft – it might have to rename itself Googol.

If you must argue, use a little expertise...

Do you believe in God? Should we eat meat? Do you think baby boys should be circumcised?

For Internet users still unsure of the answers to this type of big picture question, a promising new American website called OpposingViews.com offers a digital debating chamber for proven experts in politics, economics, culture, science and faith.

On OpposingViews, you'll find not only debaters from well-known organisations such as Amnesty International, the Sierra Club and the National Rifle Association (NRA), but also experts from less familiar authoritative bodies like the National Association of Circumcision Information (NACI).

I'm not sure if God exists and I'm certainly not going to publicly state my position on circumcision, but what I do know for sure is that this Southern Californian-based new website offers convincing proof that Web 2.0's cult of amateur content is rapidly going out of fashion. What OpposingViews undeniably proves is that the internet's new "new thing"is expertise.

You think you could be an author? Try out your book on the web

According to Clive Malcher, the Digital Publisher at Harper Collins UK, "everyone thinks they have a book in them". Therein, Malcher believes, lies the justification for Authonomy.com, an ambitious new Harper Collins website designed for unpublished authors.

Authonomy – which Malcher described as "my baby" – is a vertical social network designed to give wannabe writers a global online community for distributing, critiquing and even selling their work. Launched last week, the website provides writers with what Malcher describes as the publishing "tools to celebrate their talent".

But what happens if these writers aren't talented? I asked the London based Malcher when we spoke on the telephone last week. "Creativity is subjective," he explained. "If you can find an audience, then you have talent."

Talent might be subjective, but money isn't. So what's the economic point of Authonomy for the News Corp owned Harper Collins? Malcher acknowledged that there are few immediate revenue opportunities for the new website. But in the longer-term, he suggested in language that made Authonomy sound like a cross between an airport and a biological environment, the website can become a "hub" of a "bigger eco-system". Certainly, I could imagine Authonomy becoming a literary version of Apple's lucrative iTunes business for the sale of e-books. And while the site currently isn't selling advertisements, it would obviously offer unrivalled opportunities for both bookshops and publishers eager to reach a niche audience of hardcore writers and readers.

But I suspect the real economic rationale of Authonomy is taking advantage of the free labour of the supposedly wise online crowd. With Authonomy, Harper Collins is handing over the slush-pile to an audience of unpaid readers. They want the members of the Authonomy to sort through the manuscripts of the hundreds of thousands of wannabe authors, thereby discovering the next J K Rowling or Elizabeth Gilbert. This is what Wired magazine writer Jeff Howe, in a new book released in the UK last month, calls "crowdsourcing". Thus, the crowd on Authonomy becomes a supplement, perhaps even a replacement, for the traditional book editor and the literary agent.

As a published writer, it is, of course, easy for me to be glib about the democratising impact of Authonomy on the archaic and elitist book business. But I really do welcome this snappily designed social network. Authonomy is undoubtedly a worthwhile new online destination for the 98 per cent of people who, according to Harper Collins research, believe that they are a book author in-waiting.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments