Claire Beale on Advertising: Once again, we're being called child snatchers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

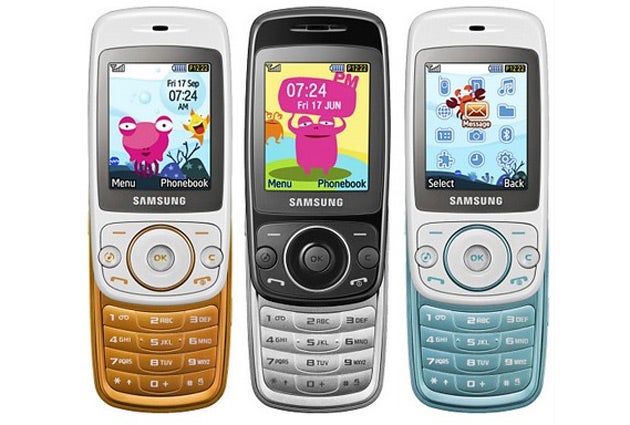

Your support makes all the difference.The Samsung Tobi comes in "sweet pink" and "loyal blue". It's cute. It's a camera, phone and music player. If you're under 12, you'll probably want one. If you're over 12 and overprotective, you'll probably seize on the Tobi as the latest example of the commercialisation of childhood.

The Tobi, aimed at children as young as six, rubs a raw nerve. In the past couple of weeks, two fresh attacks have begun against marketing to children. And, once again, advertising has been forced on to the back foot.

It's the language in Agnes Nairn and Ed Mayo's book Consumer Kids that's shocking: marketing as child abuse. It refers to the "grooming" of children by brands, or "child catchers", warning of "cyber predators" "stalking" innocents in pursuit of the £99bn kids' market (up 33 per cent in five years), £12bn of it coming from pocket money.

The net has exacerbated the problem. Nairn and Mayo say our children are being encouraged online to divulge personal details that are then used to serve them ads. And they're being recruited by businesses to promote products to friends, sometimes even for financial reward; they reckon more than half a million children have been enlisted by youth brands, and children are regularly signed up as "informers" and "lifestyle representatives" for big firms.

It's a chilling picture of a generation of children snatched from their cradles by big businesses desperate to extend their consumer base by pushing into the pre-teen market.

And, of course, it's a truly twisted view of the world; a view that fails to acknowledge the role advertising and marketing plays in providing us all with the wealth of "free" content – much of it of tangible, educational and socially valuable – we are privileged to have access to online. It's a view that seems keen to keep our children mothballed in an analogue world, passively served the content grown-ups think is good for them.

And it's a view that wilfully ignores how knowing about advertising children are now. They understand the technology, how to manipulate it and use it to their own ends in ways that can make their parents look, frankly, gullible. Of course the internet is full of traps for the vulnerable but, in my experience as a parent, marketing and advertising are the areas where children are most sceptical.

There's no doubt Nairn and Mayo will find plenty of supporters. Indeed, the very imagery they use is echoed in last week's Children's Society report, "The Good Childhood Inquiry". There, marketing is blamed for "excessive individualisation" and the premature sexualisation of childhood. The report points to a rise in emotional and behavioural problems in children from 10 per cent 20 years ago to 16 per cent today, and claims that British children are less happy than those in other developed countries.

The Children's Society has a rather traditional view of how to put a brake on this forced maturing, this despoiling of childhood innocence. I would give you three guesses what they're demanding, but it will be all too wearily familiar. Yes, the Children's Society wants to ban advertising.

OK, it's more discerning than that, but not much. The Children's Society wants to ban all advertising aimed at children under 12. And it wants a 9pm watershed imposed on all advertising for booze and unhealthy foods.

Adland's heard – and fought – it all before, of course. But anyone who thought the pressures on advertising would be eased after some successful defence manoeuvres led by the Advertising Association last year must now officially manoeuvre their head from the sandpit.

Advertising and marketing continue to be attacked as the poisons making us fat, drunk and socially dysfunctional. The trouble is that, by deploying such disturbingly hysterical language to draw parallels between marketing and the worst sort of child abuse, the latest anti-advertising assaults are moving beyond the reach of the ad industry's well-reasoned, logical arguments.

Best in show: Computer Tan (McCann Erickson)

*At the time of writing, 30,000 people have already been fooled by this fake ad. The hoax campaign by McCann Erickson told people that they could get a tan from their computers. Within a day, the lure of a sunkissed glow had drawn people to the ComputerTan.com website.

The idea was that the media played along with the hoax and fuelled further interest in the new tanning system. But 'The Sun' blew the cover last week and revealed that the campaign is actually a cunning ad for the Skcin skin-cancer charity to raise awareness of the disease. It's a shame that the campaign wasn't allowed to run a little longer before being exposed, but it's certainly got people talking.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments