Why it’s time to clock the genius of Sir Frank Dyson, the scientist who ‘crashed the pips’ at Greenwich for the BBC

At the third stroke the time will be the 150th anniversary of the birth of Sir Frank Dyson. But there’s more to him than the man who invented the Greenwich pips, says David Barnett

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Every day since 5 February 1924, the Royal Greenwich Observatory has made “the pips” available to the BBC, every 15 minutes. If you’re a radio listener you’ll generally hear them on the hour, just before the news.

Otherwise known as the Greenwich Time Signal, the pips aren’t just some aural window dressing. You can, indeed, set your watch by them; the six short beeps at one-second intervals are the world standard from which all time ravels out on Earth; everywhere is relative, plus or minus, give or take, to Greenwich Mean Time, or GMT.

Today (8 January) is the birthday of the man responsible for the pips, Sir Frank Watson Dyson. He was born 150 years ago, in 1868. Were his only contribution to British life the beloved pips, then his place in history would be assured. But there was much more to Dyson than that. In fact, Jodie Whittaker taking controls of the Tardis on Christmas Day aside, Sir Frank might be the nearest thing we have to a real-life Time Lord.

He served as Astronomer Royal from 1910 until 1933, and perhaps his most significant gift to science is effectively “proving” Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity by observing the behaviour of stars seen near the sun during the eclipse of 1919 and providing evidence for how, as Einstein had theorised, light bent in gravitational fields.

Eclipses were of great interest to Dyson. According to his obituary in the astronomy journal The Observatory, he had organised expeditions to farflung corners of the globe to observe them, including travelling to Portugal in 1900, Sumatra in 1901 and Tunisia in 1905.

But The Observatory calls his expeditions to view the 1919 total eclipse of the sun, on May 29, as “the most remarkable incident in Dyson’s whole career”. Einstein’s Relativity: The Special and General Theory was published in 1916, in the midst of the First World War, and as strange as it seems to us in this instant information age, copies of the US-published document were hard to come by in the UK because, as The Observatory put it, “of the cessation of normal scientific exchanges brought about by the war”.

The theory of general relativity states, in simple terms, that what we think of as the force of gravity arises from the curvature of time and space; it explains the motion of planets around stars, the whys and wherefores of black holes, and theorises on the origins of the universe.

Dyson thought that the best way to test the theory would be by observing light from stars during a total eclipse, with the best one on the horizon in 1919. There was only one problem and that was when Dyson started planning his trips, the Great War was in full force, and no-one could say for certain when it was going to finish.

In the face of great discouragement from the authorities and the astronomical community, Dyson went ahead and began to organise two expeditions to observe the eclipse from the best positions – Brazil and the island of Principe, off the coast of Liberia. Dyson’s obituary points out that the Armistice was signed just three months before he was due to set off.

There’s a romantic, almost Indiana Jones-esque quality about the idea of Dyson bullishly organising his expeditions at the height of the worst conflict the world had ever seen. But it wasn’t just the imperial spirit of one born in the Victorian era. Science, especially astronomy and our understanding of the universe, was at a crossroads, just as the world had been at a crossroads with the war.

The old empires and European houses that had thrived for centuries had collapsed into conflict, paving the way for a new world to emerge f. Similarly, Einstein’s theories had set the world of science at each other’s throats. As The Observatory said: “Many eminent men of science had refused to accept Einstein’s theory; this was probably due in part to the upsetting of old and ingrained ideas that it caused.”

Dyson was born near Ashby-de-la-Zouch in Leicestershire, and his parents – his father was a Baptist minister – moved when Dyson was very young to Yorkshire. He was schooled at Heath Grammar School in Halifax, later winning scholarships to Bradford Grammar School and ultimately Trinity College, Cambridge.

(Yorkshire, and the West Riding in particular, has a long tradition of turning out famous scientists; Joseph Priestley, born in Birstall, the man who “discovered” oxygen; Todmorden’s Sir John Cockroft, who shared the Nobel Prize in 1951 for his work on splitting the atom; Bradfordian Fred Hoyle, who rose to prominence in astronomy after Dyson’s death. Perhaps there’s something in the water up there, some dogged determination to not believe a thing until it’s been seen with your own eyes.)

After studying maths and astronomy at Cambridge, Dyson joined the Royal Observatory at Greenwich in 1894. He served as Astronomer Royal for Scotland from 1905 until 1910, when he took up the position as Astronomer Royal for Britain, coinciding with becoming Director of the Greenwich Observatory. He held both posts until his retirement in 1933.

In 1945, after seeing the effects of the atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Albert Einstein famously spoke of how scientific discoveries can be twisted not for the good of humanity, but for its destruction. One quote often attributed to him is: “If only I had known, I should have become a watchmaker”.

Dyson died in May 1939, before the Second Wold War had even begun, sailing back from Australia, where he had been in ill health.

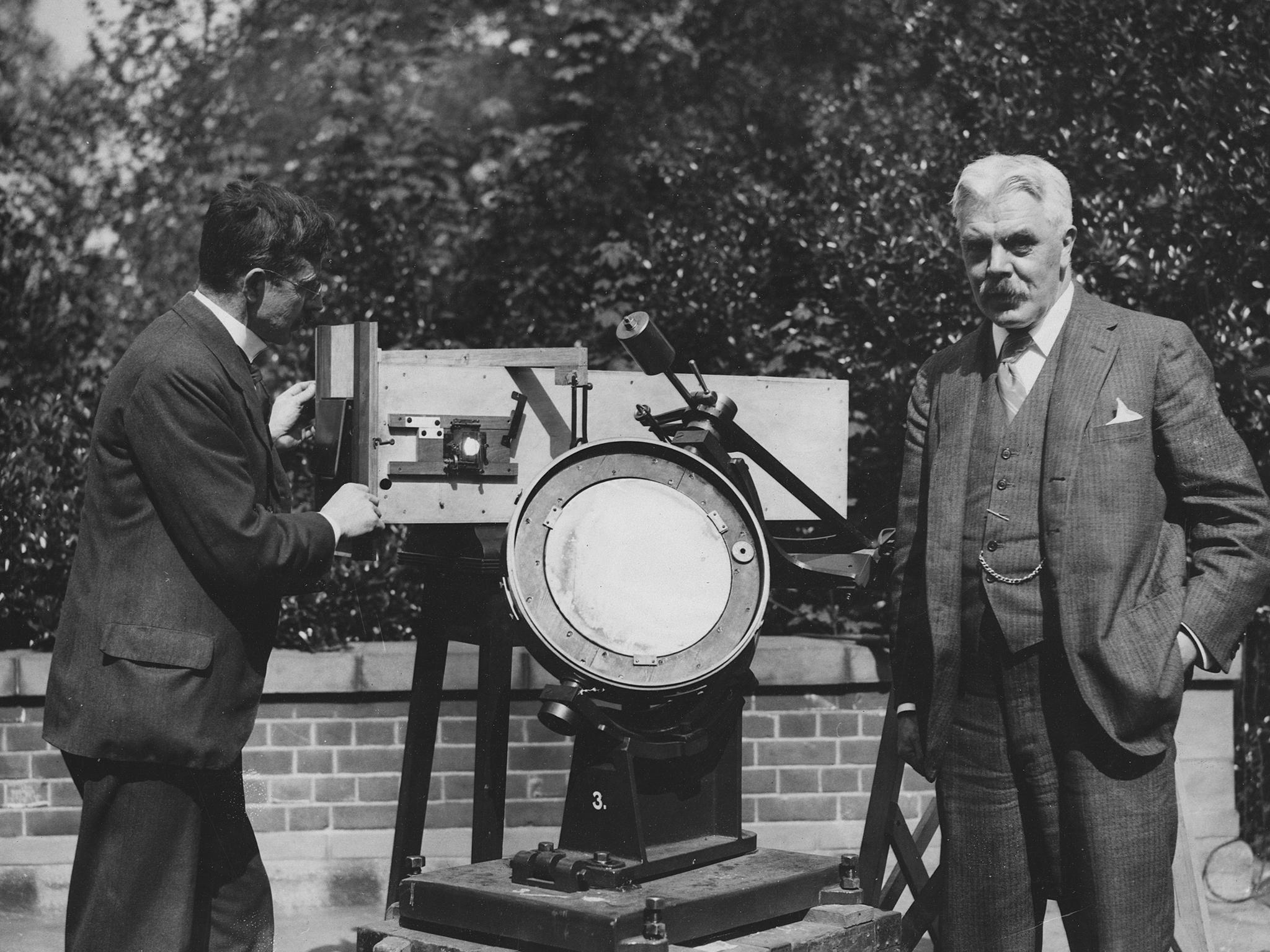

Funnily enough, it was his interest watches, clocks, and time itself, that led to his development of the famous pips. The very idea for a permanent, accurate, audible time-keeping signal was Dyson’s. Having spoken to the head of the BBC, John Reith, Dyson set to work with Frank Hope-Jones, the clockmaker, to come up with two free-pendulum clocks which marked time via two weight-driven astronomical regulators – and sent the time, as pulses of sound, to Broadcasting House in London where they were converted into the recognisable pips.

The two clocks – one was a back-up – were actually built in 1874, and served until 1949, when advances in timekeeping meant they were replaced several times until the BBC installed two of its own atomic clocks in the basement of its London headquarters, which operate to this day.

The pips have been used and adapted for all manner of things. So recognisable are they as a symbol of British life that they were incorporated into the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympic Games in London. In 2014, to mark their 90th birthday, the pips were remixed to play “Happy Birthday” for the Today programme on Radio 4.

It would be fitting if the BBC had plans for something similar to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the man who was such an important figure in British science and astronomy, but perhaps nothing can top the eulogy delivered by the vicar of Greenwich during Dyson’s funeral in 1939: “If I were asked to say what I believe was the outstanding feature of his life I would say his friendliness, beautifully natural, without a trace of patronage; it was never hard work for him to be friendly, it was part of him.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments