From Myra Hindley to Ted Bundy and the Yorkshire Ripper, what makes a serial killer tick

In fiction, everyone loves a good murder story... but real-life killers pique public intrigue just as much. Andy Martin discusses the traits that set these killers apart

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

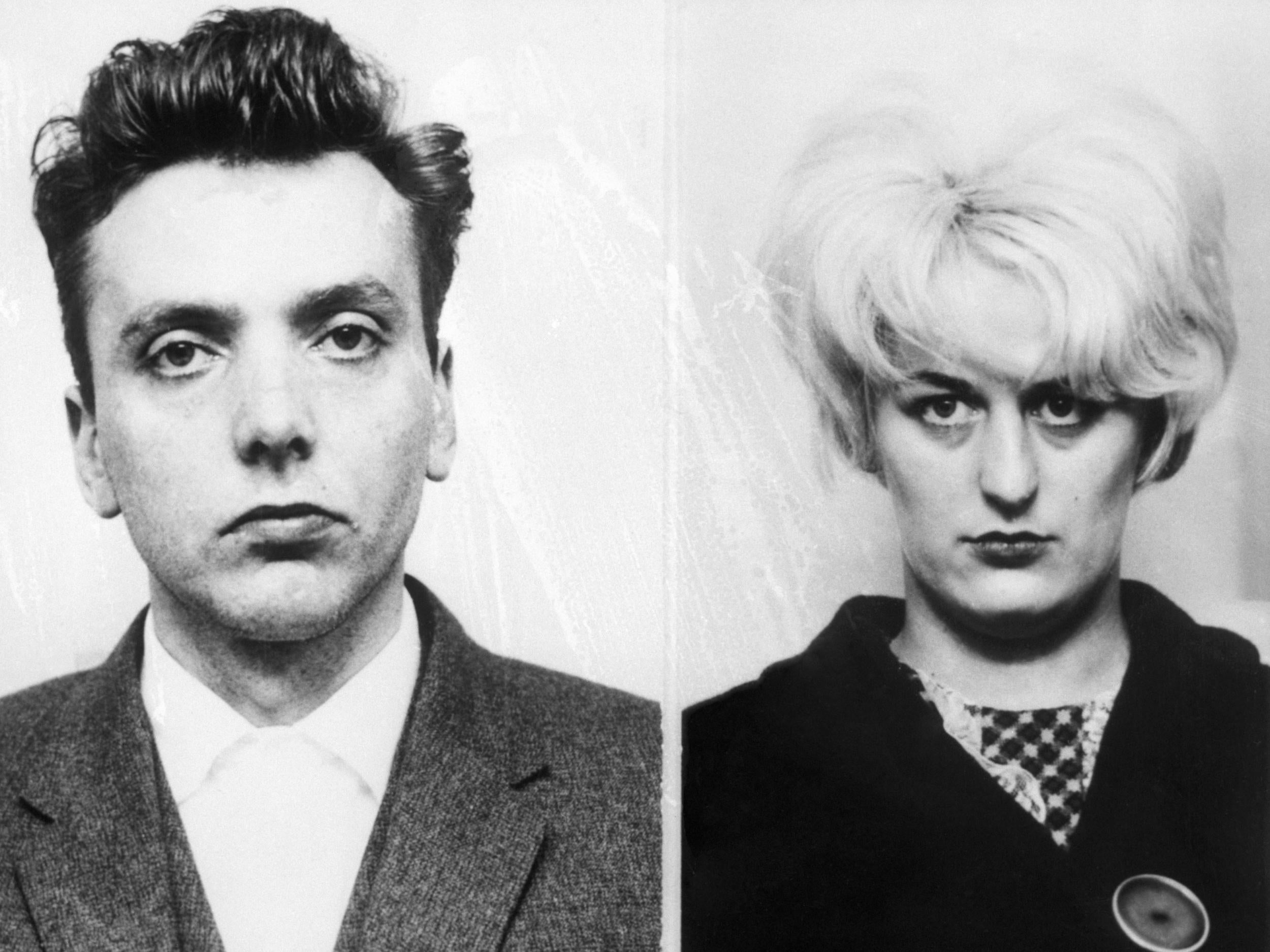

Your support makes all the difference.“If Ian Brady were to tell me it’s raining outside, I would expect sunshine,” said David Wilson. When it comes to interviewing serial killers he feels that scepticism is appropriate. More surprising is that serial killers themselves were just as dubious and initially demanded to see his CV before they would agree to talk to him. They thought he looked a bit young, fresh out of college. Shouldn’t they be speaking to a more senior man? Someone with more serious credentials?

“The arrogance of a serial killer knows no bounds,” he says. In 1984 Wilson had a viva for his PhD at the Institute of Criminology at Cambridge University on a Friday, and started at Wormwood Scrubs on the following Monday. Assistant governor at the age of 27. And one of the first inmates he had to speak to was Dennis Nilsen, the “Muswell Hill Murderer”. Now, a recognised authority on monsters and maniacs and a professor at Birmingham City University, he is presenting a series on CBS Reality TV called Voice of a Serial Killer in which we get straight from the horse’s mouth the views and opinions and unreliable memoirs of the premier league of killers and violent offenders.

Why does everybody love a good serial killer? Perhaps more the fiction than the fact of course – the charming if cannibalistic Hannibal Lecter (in Silence of the Lambs), say, as played by Anthony Hopkins. But we are hardly less fascinated by real-life equivalents. Jack the Ripper, whoever he was, even though long dead, is still iconic. On the more fictional side we have the recent Snowman film, starring Michael Fassbender, based on the terrifying yet compelling novel of Norwegian writer Jo Nesbo, who says that his job consists mainly of working out (imaginary) ways of killing people. The waterbed that, just when you are getting your pyjamas on, turns out to contain the body of the previous occupant, is unforgettable. And the guy’s in the shower, but then the shower stops…

There is a curious crossover between fact and fiction. Steph Broadribb, author of Deep Down Dead and (as Stephanie Marland) the forthcoming My Little Eye speaks for both real and literary types when she says that “serial killers give the option for a ‘chase’ narrative in a police procedural sub-genre. There is always the ‘Can they catch them before they strike again?’ question.” Noir novelist Lee Child says that the pre-eminence of the serial killer theme is “a modern expression of the most ancient human fear – “There’s something out there!”. But if the fear of death at the hand of a monster – the Werewolf – is palaeolithic in origin, the phenomenon of the serial killer is a recent development.

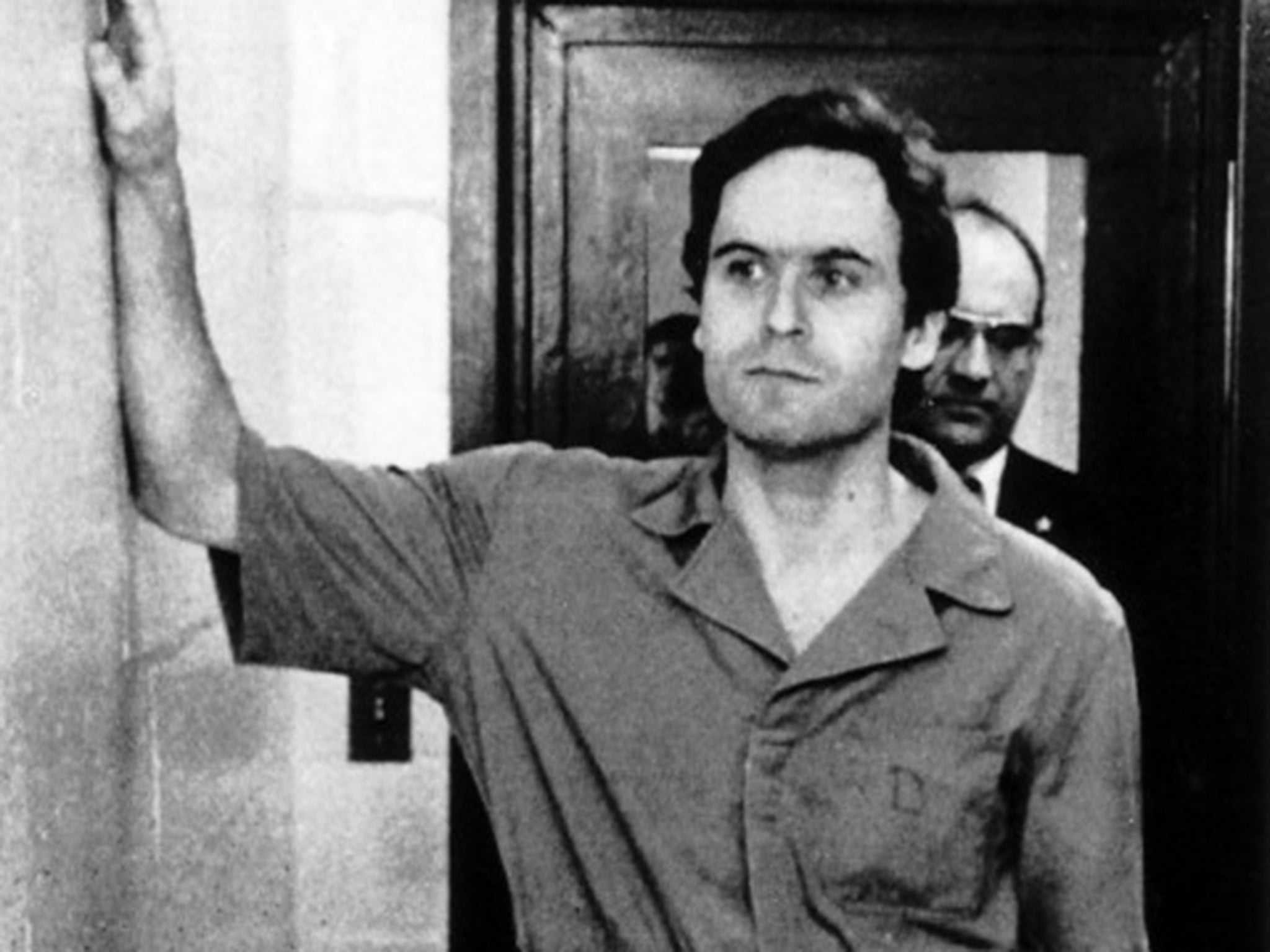

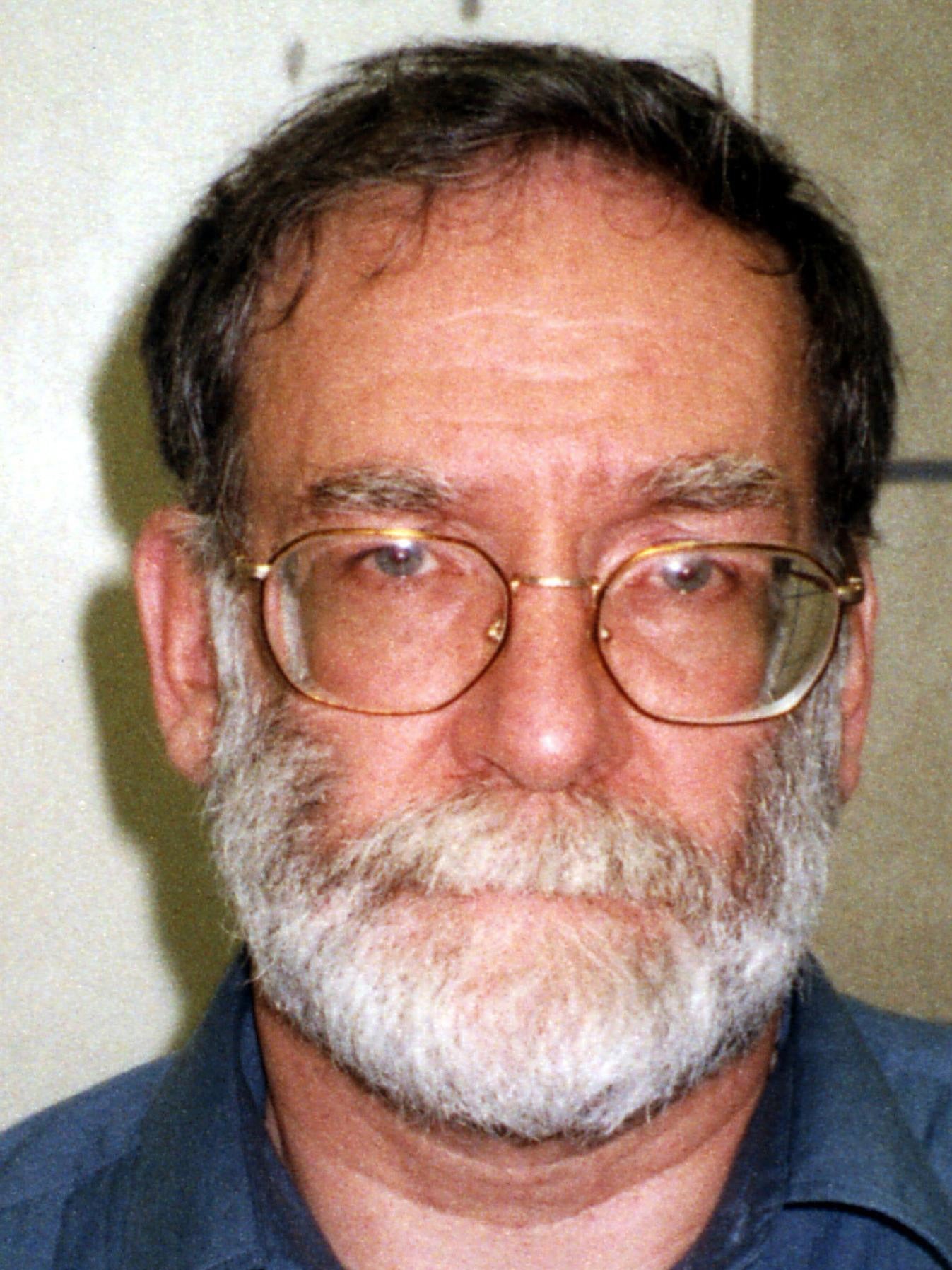

The concept itself dates only from the 1970s. FBI Agent Robert Ressler – his autobiography is Whoever Fights Monsters – is reputed to have been the first to use the the term “serial killer” in 1977, inspired by his time at the Bramshill Police Academy outside London, where they had taken to referring to a repeat offender as a “serial burglar”. The FBI – as now dramatised in the current Netflix series, Mind Hunter – took up the idea and applied it to fit such multiple killers as Ed Kemper (10 victims before he gave himself up), Jeffrey Dahmer (17) and Ted Bundy (30 or more). In South America, the “Monster of the Andes”, Pedro Lopez confessed to killing 310 pre-pubescent girls. In the UK Dr Harold Shipman killed a number of his patients estimated in the hundreds.

But this is a case where literature got there first. The Marquis de Sade, who became Citizen Sade after the French Revolution, felt that the Encyclopédie, the compendium of Enlightenment knowledge with contributors like Voltaire and Rousseau, left out one thing: crime. Sade’s novels, written in the Bastille or the asylum, such as Justine and 120 Days of Sodom provide an alternate encyclopaedia of perversion, a user’s manual to rape, flogging, torture and murder, inflicted on a string of young men and women, by ruthless libertines. Sade preached a “philosophy of selfishness”.

The worst crime Sade himself is alleged to have committed was scoring the buttocks of a prostitute and pouring wax into the wounds. But his philosophy was taken up and applied by Ian Brady for one, who also liked to quote Nietzsche and his theory of the “will to power”. David Wilson stresses that we have to take the propaganda of the serial killer with a pinch of salt. “Brady and others like him will often bring in philosophical justifications. It’s a way of glorifying themselves. It doesn’t mean that this was the origin or cause of their crimes.” In books such as A History of British Serial Killing, Wilson likes to turn our conventional approach around and focus on the victims.

He argues that it is groups within society that have been marginalised – prostitutes, gay men, young runaways – who are most at risk from the serial killer. He calls this a “structural” analysis. “Those who want to kill repeatedly are able to do only when the social structure in which they operate allows it to happen.” Sadism coincided with the French Revolution, when according to Marx, feudalism gave way to capitalism. The rise of the serial killer, through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, is an extreme (and of course illegal) embodiment of the tendency of capitalism to tear things apart, what theorists such as Joseph Schumpeter like to refer to as “creative destruction.” The serial killer is the dark anti-hero of unconstrained global capital. On the one hand we have the rip-off, on the other we have the Ripper.

Adam Smith spoke of the “invisible hand” that conveyed its benefits; the more visible bloody hand and associated instruments of the serial killer have been there to provide a corrective to any utopianism. The 1980s under Thatcher was the golden age of British serial killing (at one point there were at least 3 on the rampage simultaneously). If there was no society then everyone was a potential victim and, after all, who would even care? Wilson writes that “only when bonds of mutual support have been all but eradicated can those who want to kill large numbers of their fellow human beings achieve their purpose.”

The characteristic signature of the serial killer is the message to the police. “Son of Sam” killer, David Berkowitz, wrote letters addressed to detectives on the bodies of his victims, taunting pursuers and promising further crimes: “I am deeply hurt by your calling me a women hater. I am not. But I am a monster… I live for the hunt.” Bad guys typically read up on and learn from what the good guys are doing. Ed Kemper read Joseph Wambaugh, ex-LAPD detective. In London, in 1993, Michael Ireland, who was a fan of Ressler’s Whoever Fights Monsters, went so far as to phone up the police twice, to urge them on and rebuke them. “Doesn’t the death of a homosexual man mean anything? I will do another.” In the case of the Yorkshire Ripper, Peter Sutcliffe, the police were thrown off track for a time by hoax tapes sent to them by someone claiming to be the Ripper (actually John Humble). The police more or less expected something like this and took it all too seriously.

We can also take what the serial killer has to say too literally. The Mind Hunter series turns the FBI around from total scepticism about talking to obvious maniacs to an evangelical belief in the “insights” that murderers can provide. But this then verges on a naive reading of what are inevitably unreliable narrators. “You have to be a good literary critic to interview them,” says David Wilson. “All serial killers are desperate to keep hold of the narrative. They are skilled at it. They are fantasists. And they are trying to control their image.”

Wilson also notes that there is now a big divide between interrogation techniques on opposite sides of the Atlantic. The US favours the so-called “Reid” technique, which is accusatory and articulates a realistic narrative that the accused is then asked to acquiesce to (“Where did you put her head?”) But miscarriages of justice are frequent as a result of “coerced compliant confessions” in which the accused gives in to escape further interrogation, or “coerced internalised confessions”, in which, as in The Making of a Murderer, an innocent man comes to believe in his own guilt.

In the UK, in contrast, we have a more “investigative” approach to questioning which assumes nothing in advance. The accused is not prompted with crucial pieces of evidence, thus enabling the police to exclude “voluntary false confessions”. The turning point in our history came with such procedural disasters as the Birmingham Six, and the Bridgwater Four, which amounted to little more than rounding up the usual suspects, except that in each case confessions were extracted from people who had no involvement in the crime.

The career serial killer is ambivalent towards police pursuit. On the one hand, killers want to evade capture to carry on killing; on the other hand, they want the police to know that they are evading capture and are good at it. So murder must advertise. This is late modern killing, which feeds on publicity and notoriety. Murder is not enough. It barely registers on social media. These days you need to kill big to make a splash. Either you have to be a spree killer (as, most recently, in Las Vegas) or a long-term serial killer, aiming to get the numbers up slowly, patiently, generally one at a time. The serial killer is all about the steady accumulation of symbolic capital in the minds of police and the public at large. Where will they strike next? Meanwhile, as in a video game with real blood, you are clocking up points and getting rewards even as you knock off victims.

In their pursuit of fame and attention, the serial killer provides a mocking commentary on our contemporary notions of “self-realization”. The self can only fully be realised, the Sadeian killer says, at the expense of the deconstruction and annihilation of the other. Even at the expense of their own eventual extinction. So long as they leave a trace, not just on the body of individuals, but in the mind of society as a whole. There will always be something – or someone – out there.

Black Widows and Angels of Death

Women are vastly over-represented among the victims of serial killers. It’s a classic gender asymmetry. Serial killing is a predominantly male phenomenon. But women do also figure among the ranks of the perpetrators. In the nineteenth century, Mary Ann Cotton succeeded in murdering as many as 21 of her friends, relatives, husbands, and children, over more than a decade, using the favoured tool of Victorian killers, arsenic. It was easy to mistake the symptoms of arsenic poisoning for common illnesses such as cholera or pneumonia. She was hanged in 1873, but was eclipsed in the following decade by Jack the Ripper. The Ripper worked in the open, killing women randomly in the streets of Whitechapel, whereas poisoning is a more private, domestic affair. Moreover Cotton lived in the North-East of England and the main media channels of the nineteenth century were clustered around London and gave disproportionate attention to their own backyard.

The best-known female serial killers of the 20th century, such as Rose West and Myra Hindley, have been willing participants in what the specialists refer to as a “folie à deux”, a criminal partnership in which the woman teams up either with her husband (Fred West) or boyfriend (Ian Brady). In America Susan Atkins, Lynette “Squeaky Fromme, and Patricia Krenwinkel were all members of the so-called “family” in thrall to Charles Manson. Even killing can be seen as part of a relationship. But there is at least one recent case of a woman, Joanna Dennehy, who killed or attempted to kill several men in 2013, and modelled herself on Bonnie Parker of Bonnie and Clyde fame, and who dominated and dragooned her male accomplice, Gary Stretch.

The paediatric nurse, Beverley Allitt, who murdered four children in her care and attempted to murder several more, inevitably attracted the label, “Angel of Death”, since she was working, like Shipman, in the health care environment. She was diagnosed as suffering from Munchausen syndrome by proxy, in which the killer goes about drumming up business for her therapy and sympathy. As David Wilson points out, the female serial killer “disrupts our gender stereotypes”, subverting the image of the caring, nurturing, empathic mother/wife figure. Alternative stereotypes such as “The Black Widow” rush in to take its place. In the realm of contemporary fiction, Alexandra Sokolov’s “Huntress” series features a serial killing female protagonist, who kills men guilty of crimes against women.

Voice of a Serial Killer is being broadcast on CBS Reality on 1 November

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’. He teaches at the University of Cambridge.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments