Roll up, roll up, for the greatest showman on earth: How Philip Astley created the modern circus

As we celebrate the 250th anniversary of the UK's first modern circus, David Barnett investigates the life of one of its principal inventors

Circuses are big news again this month, whether it’s the glitz and glitter of The Greatest Showman, the Hugh Jackman-led movie about the life of showbusiness entrepreneur PT Barnum (in cinemas now), or the altogether darker thrills of Pennywise the evil clown in the imminent DVD release of the adaptation of Stephen King’s horror novel It.

But there’s another reason to celebrate the roar of the crowd and the smell of the greasepaint in January, and that’s because 9 January marks the 250th anniversary of the forerunner of the first modern circus in the UK… pre-dating Barnum by almost a century.

Britain’s Barnum was a man called Philip Astley, who was born around 1742 in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire. He initially worked with his father Edward, who was a cabinet-maker in the market town, but in 1759 Astley enlisted with the 15th Light Dragoons, and it was from his budding military career that the seeds for the modern circus were sown.

Proving himself adept at horse riding, Astley came to the attention of a man called Dominic Angelo, Lord Pembroke’s horse trainer, and he selected the young Astley to be trained in a series of new methods which included trick riding, training and “subduing” horses.

Astley carried out his tuition at Lord Pembroke’s estate in Salisbury, and his subsequent service in the Seven Years War in the mid-1700s allowed him to put his new training into practice, earning him a reputation as a master of equestrian skills and setting the scene for his post-military career: the invention of the circus.

Of course, the concept of the circus goes back even further than 250 years since Astley had his bright idea. The very word dates back to Roman times, when citizens would gather at the vast Circus Maximus on the plain between the Palatine and Aventine hills to watch displays of horse riding and gladiatorial combat.

That staple of circus life – the clown – goes back even further, with roots in medieval court jesters and even in performances given during the Fifth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. The modern idea of the clown grew out of the commedia dell’arte that originated in Italy in the 16th century, and spread across Europe for 200 years, solidifying into the early 18th Century portrayal of the clown as typified by Joseph Grimaldi’s turns on Drury Lane and Covent Garden.

But it wasn’t laughs on Philip Astley’s mind in January 1768 when he took his horse to an open field in Waterloo, London, just behind what is now St John’s Church. Astley had a dream of opening a riding school which would also double up as a performance area for the public, where he and his riders could display the acrobatic equestrian skills he had learned from Dominic Angelo and perfected during his cavalry years.

On that field, with musical accompaniment on a drum from his wife Patty, Astley made one crucial change to the other equestrian performances he had seen: rather than riding in a straight line, he performed his tricks in a tight circular route, effectively inventing the circus ring that became standard in the following decades.

Indeed, the 42ft-diameter ring that Astley created is still used today. We cannot, says Andrew Van Buren, overestimate Philip Astley’s contribution to modern culture in what he did 250 years ago. “In fact, I’d go as far as to say that Astley is our William Shakespeare.”

By “our”, Van Buren means circus folk, and it’s a life he’s steeped in as an illusionist, juggler and plate-spinner. His father is Fred Van Buren, a noted illusionist now aged 85, who as a young boy actually ran away to join the circus in Sandbach, Cheshire. It was through his father that Van Buren not only learned to love the circus, but also developed a keen interest in Philip Astley.

Van Buren says: “Although he joined the circus, eventually doing some clowning and trapeze work, he still had to be schooled, and it was while at school he read a book that mentioned Astley, and became fascinated.

“When his parents insisted that he find an apprenticeship when he left school, he became a cabinet-maker’s apprentice. Nobody knew that he was secretly following the path that Philip Astley had done.”

While Astley might not be as well known as PT Barnum, his life would make an equally, perhaps more, engrossing movie. He was a physically imposing figure, broad and more than 6ft tall, described by one biographer as having “the proportions of Hercules and the voice of a Stentor [a figure from Greek mythology with a booming voice]”.

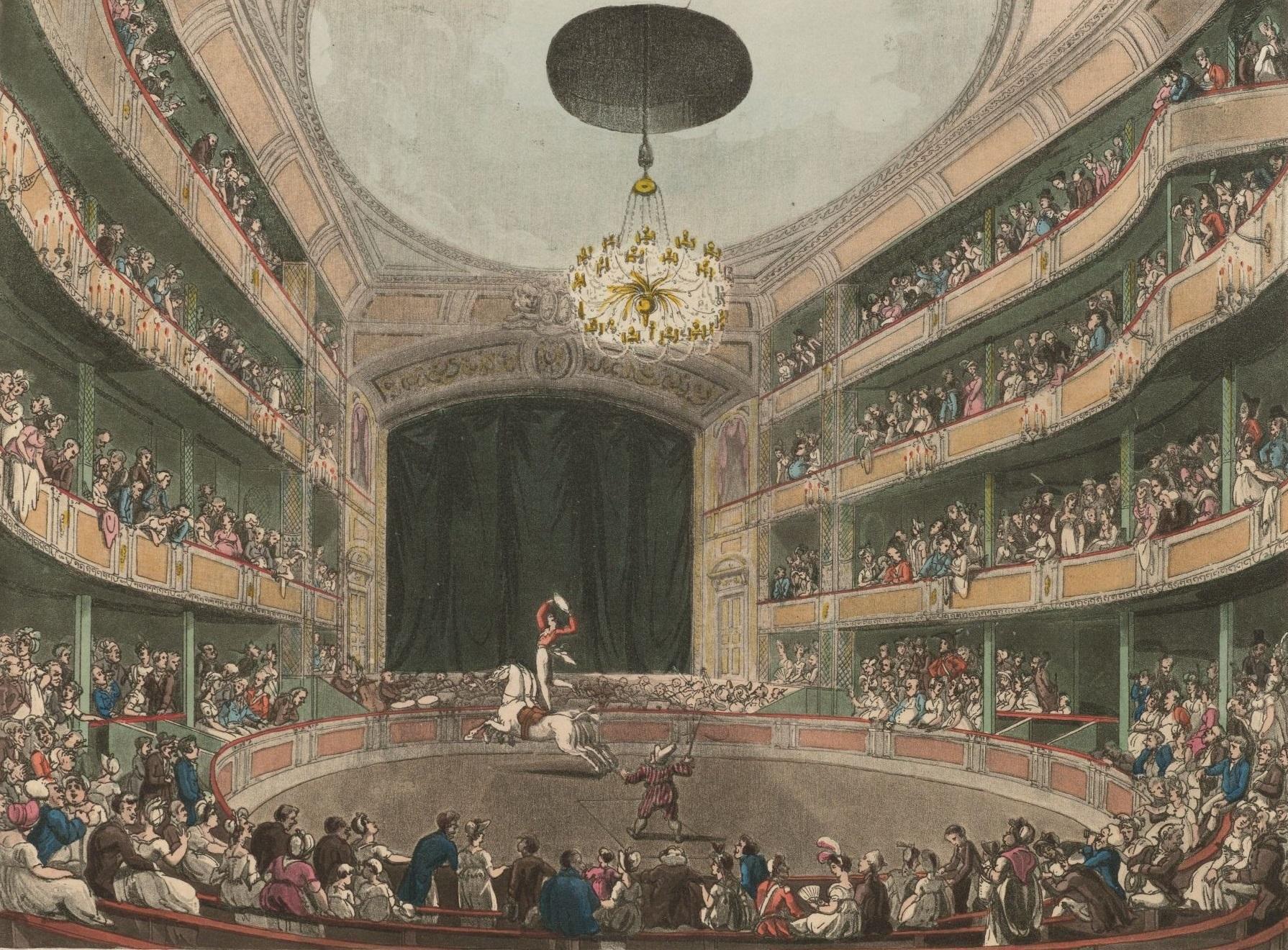

Having established his riding school and getting audiences to pay to watch exhibitions, he then developed the circus, moving to a bigger site near Westminster Bridge and bringing in clowns, high-wire acts and acrobats to entertain the citizenry between equestrian displays.

He became so successful that he eventually had 19 amphitheatres, one of them in Paris. When the French Revolution broke out, Astley was captured, then escaped and made his way back to England. He returned to see if his amphitheatre was intact; it was, and Napoleon was using it as a barracks. Van Buren says: “Astley was such a canny businessman that he submitted a claim for rent to Napoleon, who duly paid up!”

Astley died in 1814 and is buried in Paris’s famous Pere Lachaise cemetery, having ushered in the age of the circus. Still, though, he’s not as famous as he should be, which is something that Van Buren has been trying to change, especially in Astley’s home-town of Newcastle.

Van Buren says: “I’ve had three goes at trying to get him the recognition he deserves. The first time was in 1981, when my father was asked by Newcastle council to organise their carnival. We suggested it should be in honour of Philip Astley, and the general response was, ‘Who?’.

“Then, in 1992, which was the 250th anniversary of Astley’s birth, we had a life-sized bronze resin statue made to celebrate. There was more interest this time, but after the date [Astley’s birthday is actually 8 January 8] it waned a bit.”

Then, in 2010, Van Buren decided to have another go, working towards marking the 250th anniversary of Astley’s first circus in 2018. For the past three years he’s been working with the local authority and Kat Evans at Staffordshire University to stage a year-long celebration in Newcastle-Under-Lyme. It’s third time lucky for Van Buren, as Astley’s hometown has finally taken the father of the modern circus into its heart.

There are talks, film showings, art exhibitions, museum events and, in August, “AstleyFest”, a circus-themed gala event to finally put Philip Astley on the map, all under the banner of the Philip Astley Project.

And it’s not just in Staffordshire where Astley is being remembered. Circuses across the world, from Budapest to Monte Carlo, are recognising the anniversary. “It’s incredible it’s finally happening,” says Van Buren of his labour of love.

Circuses have evolved through several stages since Astley first measured out his 42ft-ring in 1768. In his lifetime there were no animals in circuses; that came later, a couple of years after his death, when American animal trainer Isaac A Van Amburgh married up the idea of the travelling menagerie – portable zoos, basically – with what was on offer at the circuses, and introduced big cats and elephants.

In a way, circuses have come full circle as animal acts have fallen out of favour these days. Many circuses are human-performers only; some, like Philip Astley, offer equestrian acts alongside the clowns and acrobats.

The RSPCA is against animal performances, saying, “Travelling circus life is likely to have a harmful effect on animal welfare as captive animals are unable to socialise, get enough exercise or exhibit natural behaviours.

“Many animals develop behavioural and/or health problems as a direct result of the captive life that they are forced to lead.”

“Circuses have always evolved, and are still evolving today,” says Van Buren. “People say that this is not a good period for circuses, but I disagree. In fact, I believe we’re in a golden age for circuses; there’s so much diversity at the moment.”

It might be PT Barnum who is remembered for his showmanship, but he’d be nowhere without Philip Astley, the military hero who set up shop on a muddy field in the cold, harsh winter of 1768 and invented the modern circus.

In fact, given his interesting life – charging into battle, capturing seven enemy standards, using his equestrian skills to set up the world’s first circus and charging Napoleon rent – it perhaps should be Astley who is the focus of a blockbuster movie. Now that really would be the greatest show on Earth.

For more details about the Philip Astley Project go to www.philipastley.org.uk

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies