Frank Lloyd Wright: How the master of Mid-century style is still packing an architectural punch 150 years later

Oliver Bennett looks at the architect's impact on 20th-century housing and his lasting legacy, which could yet see a FLW house built in Somerset

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

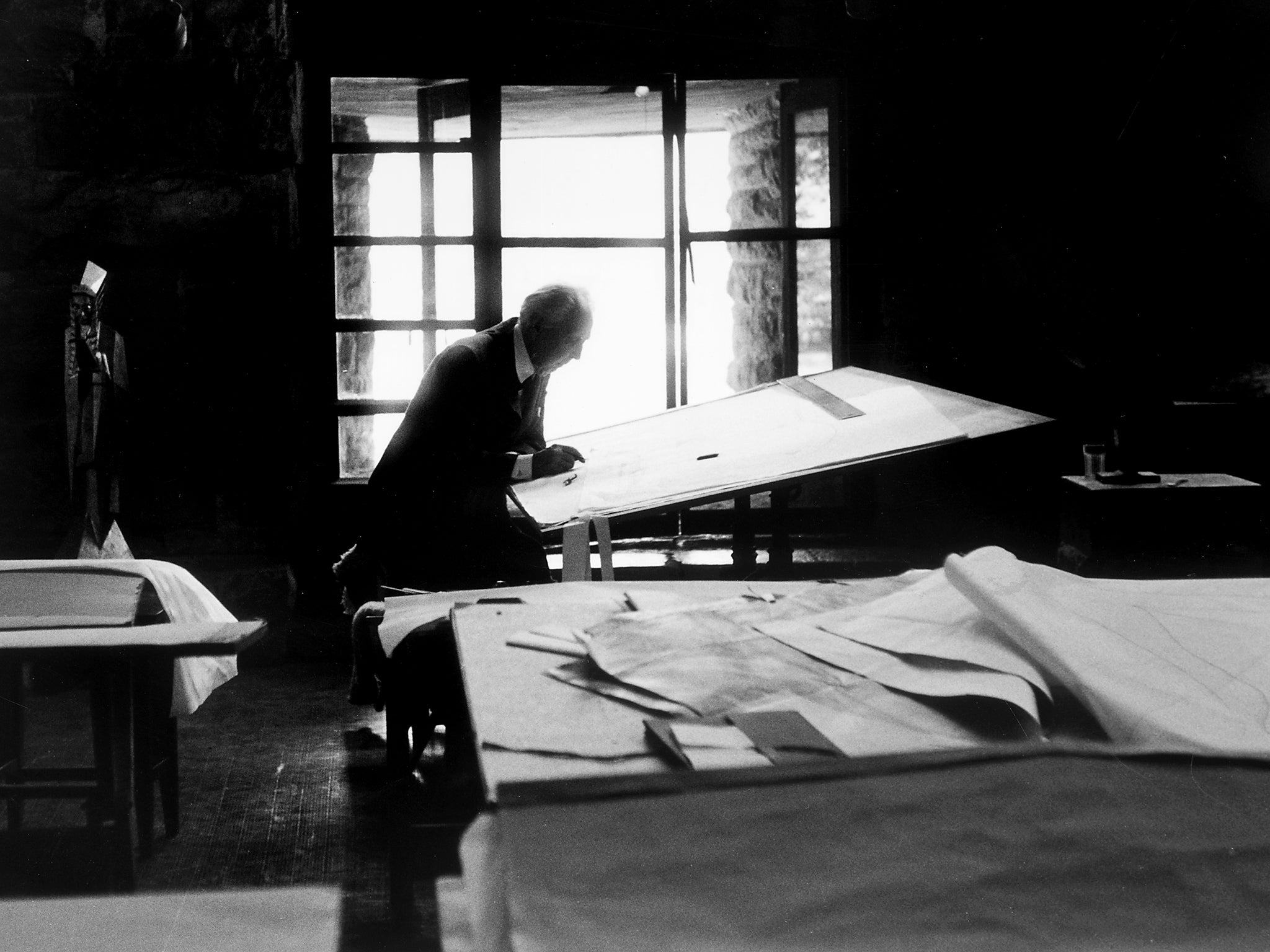

Your support makes all the difference.Taking the elevated train out of Chicago is in itself, a trip through America. You leave the central skyscrapers behind and head over slum and suburb to outlying Oak Park, where in the early 20th century, Frank Lloyd Wright lived and worked. Now, as an incessant snake of slow-moving tourists testifies, Oak Park has the greatest concentration of Wright-designed buildings anywhere in the world, including the master’s home and studio.

The district is particularly busy at the moment, as it’s the 150th birthday of Wright: the “sesquicentennial”, as they say here. And although he died long ago in 1959, Wright’s reputation has continued to soar, and his 400-odd buildings, built and unbuilt, are if anything increasingly venerated.

Indeed, it’s surely no overstatement to say that Frank Lloyd Wright is one of the few “name recognition” architects in the world – and while this might be due to Simon & Garfunkel’s 1970 musical curiosity So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright (“Architects may come and architects may go and/Never change your point of view”), it’s also because, as the American Institute of Architects puts it, he’s “the greatest American architect of all time”, a lustrous and muscular addition to the American century, when the New World overtook the old. As the Smithsonian magazine rather jingoistically has it: “In his unshakable optimism, messianic zeal and pragmatic resilience, Wright was quintessentially American.”

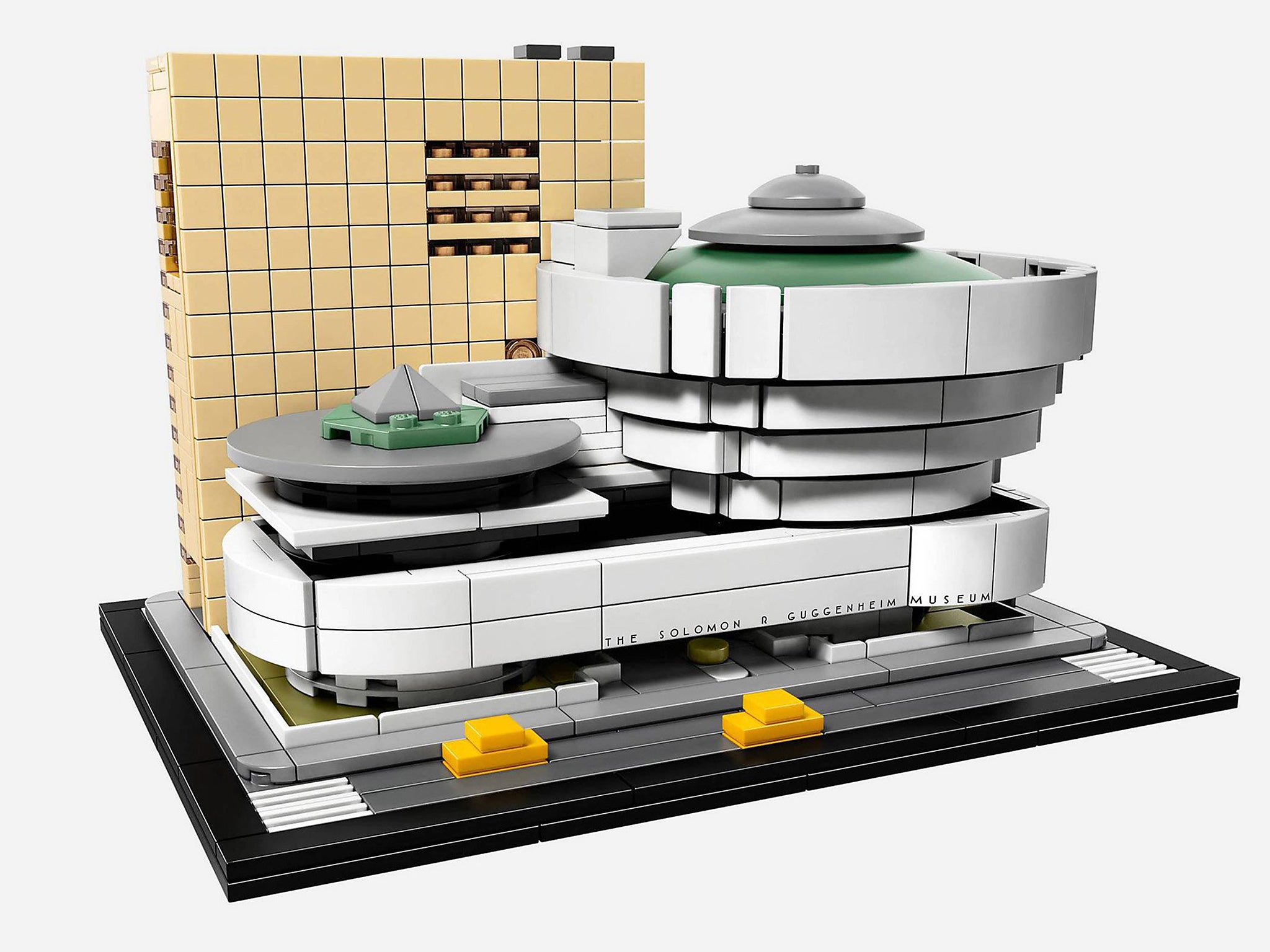

So, FLW is truly canonised – and merchandised. This year you’ll find Wright fabrics, baseball caps and Lego – a new addition to its architectural model series is Wright’s masterpiece, the Guggenheim Museum in New York. There are several new books, tours and exhibitions, notably a big show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York – see a fuller list of attractions below.

“He’s a folk hero in the US, who speaks to that American frontiersman spirit,” says Gwyn Lloyd Jones, whose new book Travels With Frank Lloyd Wright (Lund Humphries) looks at Wright’s escapades to Japan, Germany, Russia, the UK, Italy and the Middle East. “It’s amazing to think that he was born a few years after the civil war, and died in the post-Second World War era, and was a visionary of the Mid-Century era.”

He helped to develop an American identity, including his “prairie school” homes, some with vaguely meso-American markings, and a kind of “diffusion range”, his single-storey Usonian houses. Yet Jones has also traced his influence across the world, including in the UK, where Wright did a series of lectures in 1939 at RIBA that proved highly influential.

“His was quite a global vision,” says Jones. “Here, they took his ideas of dispersed living, organic architecture and buildings as harmonic responses to site and landscape seriously.” Indeed, Wright’s various innovations have spread worldwide, including a pioneering use of passive solar heating, open-planning and soaring atriums. British architects that were particularly influenced by him have included Ted Cullinan, Denys Lasdun and Richard MacCormack. Romantically, he was Welsh, calling his home “Taliesin” after the poet of antiquity, and taking the “Lloyd” from his mother’s Welsh ancestry. Yet his only notable non-US buildings are in Japan.

An American hero, then. But there was another side to him, and Jones refers to Wright’s private life as “famously colourful”. His minister father left when he was 17, never to be seen again, and Wright himself blazed a somewhat despondent and tragic trail though three wives and seven children, once writing “I hated the sound of the word Papa”.

Professionally arrogant and autocratic, he declared himself in court to be “the world’s great living architect” on the basis that he was under oath to tell the truth, and left a lot of wreckage for one whose avowed hope was that architecture should express “the highest possible expression of the individual as a unit not inconsistent with a harmonious whole”.

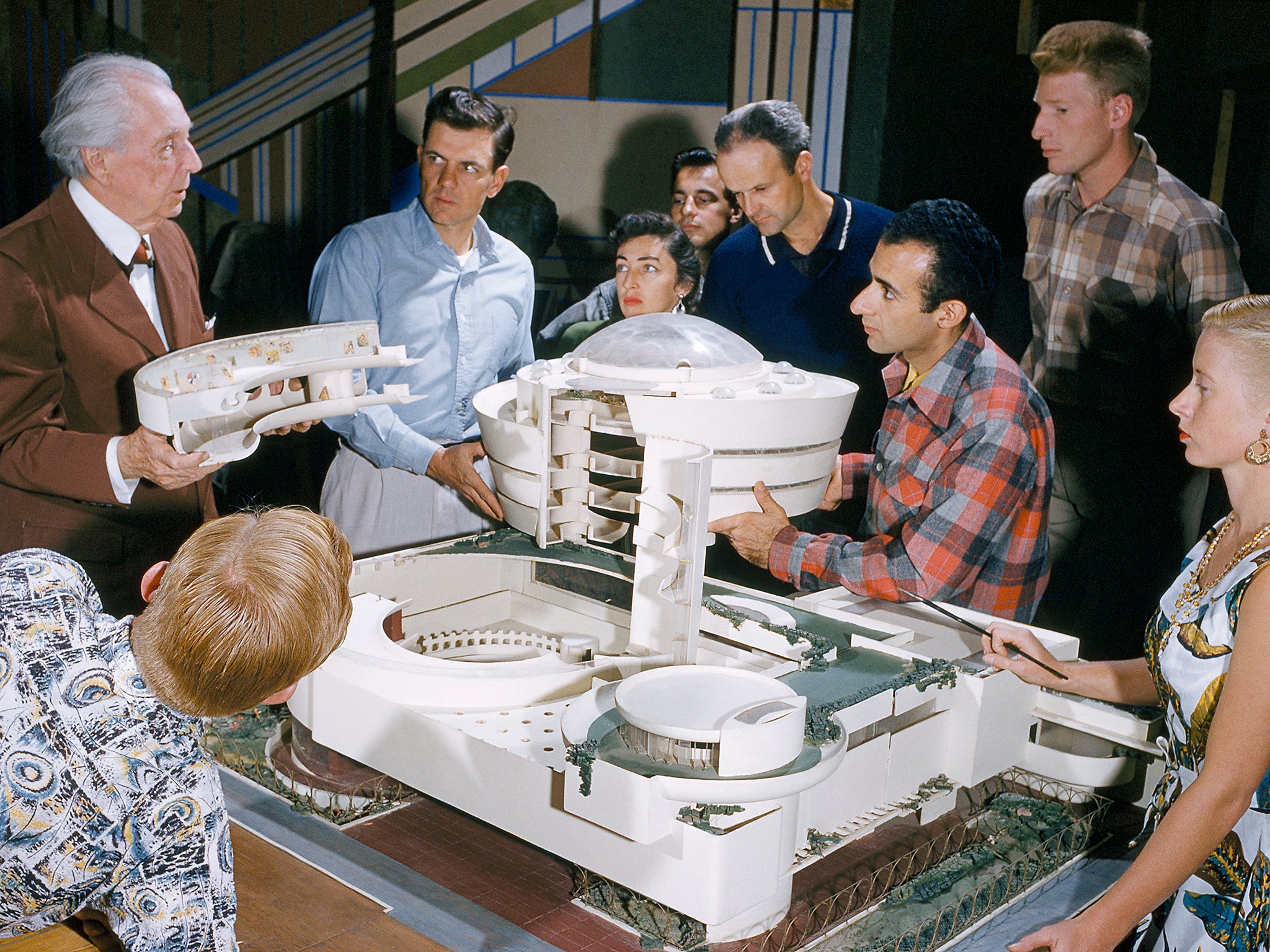

He could be politically unwholesome as well as ungracious: MoMA curator Barry Bergdoll recently described him as “both a social progressive and incredible curmudgeon”. Also, some of his buildings have had long-term problems such as leaks and cracks, leading to posthumous questions still being asked about his engineering acumen. That he was ambitious was not in question. Wright died at the age of 92, three months before his great masterpiece opened, the Guggenheim Museum in New York – and even at an advanced age he remained a trailblazer, holding a conference at 88 to propose a skyscraper that would be a mile high.

FLW places to visit in 2017

Gwyn Lloyd Jones is discussing Wright as an international architect at the AA Bookshop on Thursday 15 June, 6.30pm-8.30pm, as part of London Festival of Architecture.

The Price Tower, Oklahoma. This 1956 skyscraper became a hotel in 2003, and also hosts an Arts Centre with plentiful anniversary events this year pricetower.org

Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive is at MoMA, New York, 12 June-1 Oct moma.org/calendar/exhibitions

The Guggenheim NY’s snail-like ramp overturned the idea that an art gallery must be a series of connected rooms. It celebrates Wright’s anniversary with a reduced admission of $1.50 (£1.20) and among other things, a renovated cafe guggenheim.org

Robie House in Chicago is an early years FLW classic, considered the finest example of the “Prairie” style. flwright.org/visit/robiehouse

Fallingwater in Pennsylvania is, along with the Guggenheim, FLW’s best known building, designed for a department store tycoon in 1937 and in dramatic position over the gushing Bear Run creek. A museum since 1964. fallingwater.org

Kentuck Knob is also in Pennsylvania, in Stewart Township. Owned by the Palumbo family, it’s a horizontal delight with a sculpture garden. kentuckknob.com

Oak Park in Chicago has guided bike tours of 21 Wright sites throughout the summer, $45, see flwright.org

Buffalo, NY, attractions include the All Wright, All Day Trolley, an $130 tour of the city’s top Wright masterworks, including the Martin House, which has had a $50m restoration www.visitbuffaloniagara.com/

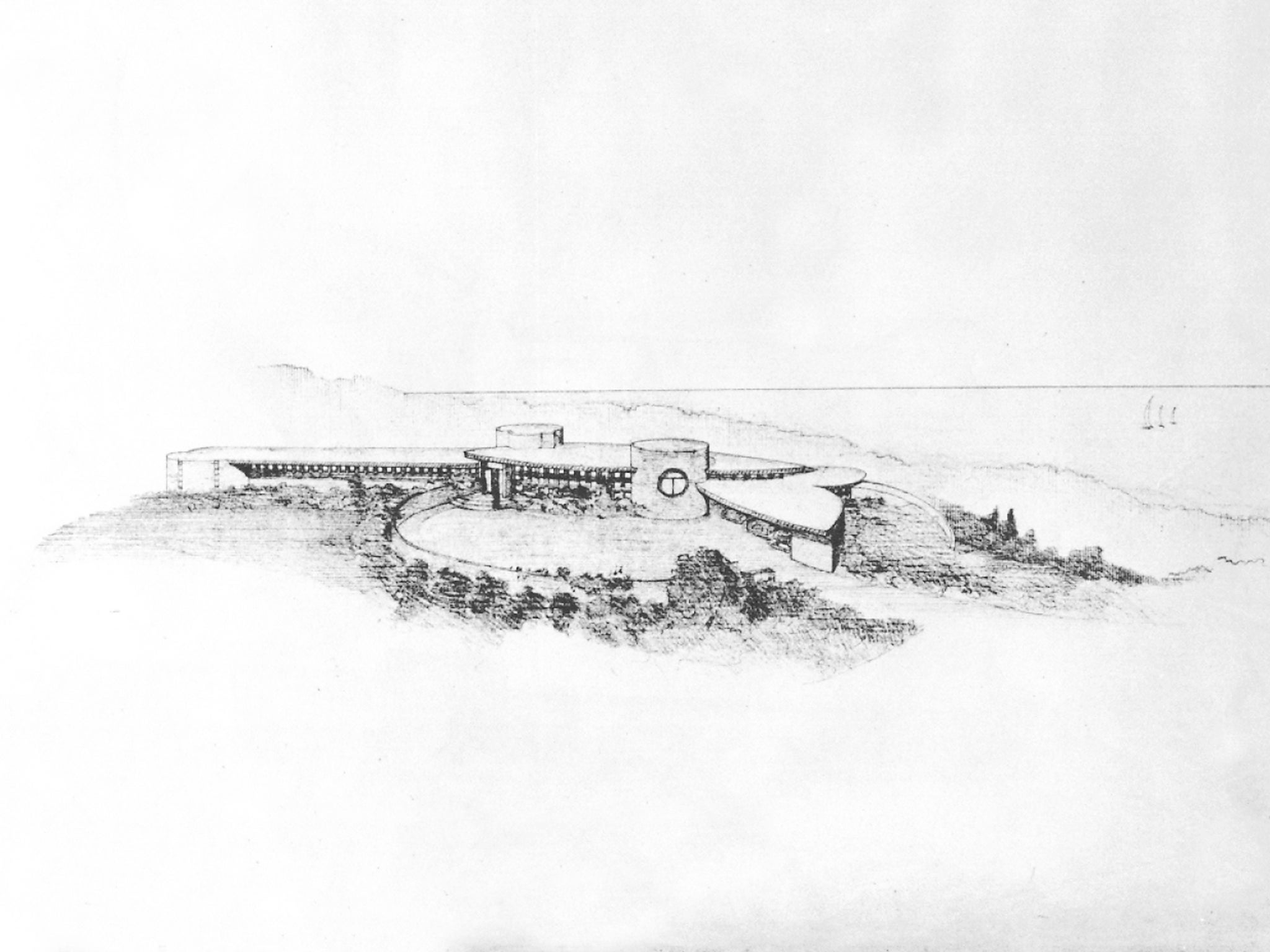

But could FLW history still be made – right here in the UK? It's the sincere hope of Dr Hugh Pratt, who is seeking to build one of Wright’s unbuilt designs, the O’Keefe House of 1947, at a site in Tyntesfield, in North Somerset. A planning proposal has just been presented, which can currently be seen on the North Somerset website. If successful, it’ll be the first Wright house in Europe.

It has been a labour of love for Wright fan Pratt, who runs a crane safety company, and who began by going to see the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in Taliesin. “I said, ‘I'd love to build a Wright home. Can you give me a design?’ And as it turned out, under certain circumstances, they could.” As it happened, there remain about 50 unbuilt FLW plans, each subject to stringent intellectual property and building conditions. Pratt joined forces with Stephen Nemtin, a senior architect with FLW’s firm, who approved the site and Pratt’s purchase, then asked Bath-based Stephen Brooks Architects to work on it.

In 2013 Nemtin died, and without his guiding input, the remaining 49 plans have been mothballed. “So it’s the only opportunity left to build a Wright house, and it would be an enormous privilege and an asset for the UK,” says Pratt, who likens it to “having a Picasso”, and adds that if built, he’ll allow visits. A couple of years ago it was turned down by the local authority planners for (among other reasons) not being “innovative” enough for its Green Belt site, which Pratt contests. “Wright was a pioneer of green design and was driven by the idea of working with each site.”

Now, with approval from Lord Richard Rogers among others, it has just been re-presented to North Somerset. Don’t say “so long” to Wright just yet.

Milwaukee Art Museum is showing an exhibition ‘Frank Lloyd Wright: Buildings for the Prairie’, showing from 28 July-15 Oct. mam.org

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments