John F Kennedy's legacy: 100 years on

He was the first TV president and with his wife Jackie they were idolised by many and since his assassination in 1963, he has been immortalised in time as a heroic figure. But, asks Youssef El-Gingihy, if his presidency carried on into a second term, would he have remained so popular?

JFK – those three letters complementing each other as they come trippingly off the tongue – is commemorated in a network of place names, bequeathing the slain President’s legacy on a grid of boulevards, squares and space centres.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy – today is the centenary of his birth – was, the oft trotted-out cliché would have it, the first modern politician – the first television president. Indeed, he laid down the template that many politicians have since emulated – the Western equivalent of the cult of personality. Without JFK, there would have been no Clinton, Obama, Blair or even Cameron. Many will feel that is hardly an endorsement.

This has reshaped our politics to the degree that a leader is deemed electable or unelectable based on the projection of a media image or persona. The debonair Kennedy deployed this to devastating effect in the inaugural television debates against a haggard Nixon. In reality, it was cortisone that allowed Kennedy to radiate vigour and his perma-tanned complexion was partially due to Addison’s disease.

In fact, presidential contests since have panned out predictably in the same mould. The winner of Reagan-Carter, Bush Sr-Clinton, Bush Jr-Gore and Obama-McCain could all have been called on the basis of personality and were really the same contest replayed over between a political celebrity able to manipulate his target audience against an occasionally more worthy opponent, who nevertheless was unable to connect with voters.

Over here, it takes us a bit of time to catch up with the Yanks. Tony Blair would be the prodigal son for this new kind of politics with the rebranding of New Labour. Though the Major and Blair eras were contiguous, the difference in presentation might as well have been measured in light years.

Yet for every disciple of the Kennedy school of PR, there are those who studiously ignored it – Margaret Thatcher comes to mind. Yet even Maggie was forced to undergo a makeover at the behest of her advisors. JFK was preceded by Eisenhower and followed by Lyndon B Johnson (LBJ) – two of the most image-averse presidents ever to occupy the Oval Office. But that shift from Eisenhower to JFK signals a quantum leap from the old world into the new, from the staid post-war 1950s into the space age.

The point is that JFK wrote the rule book we are still following. He created the climate for this new kind of politics and we are still caught up in his tailwind. This is part of the reason that half a century on he seems to exert such fascination and enthral even those born after his death.

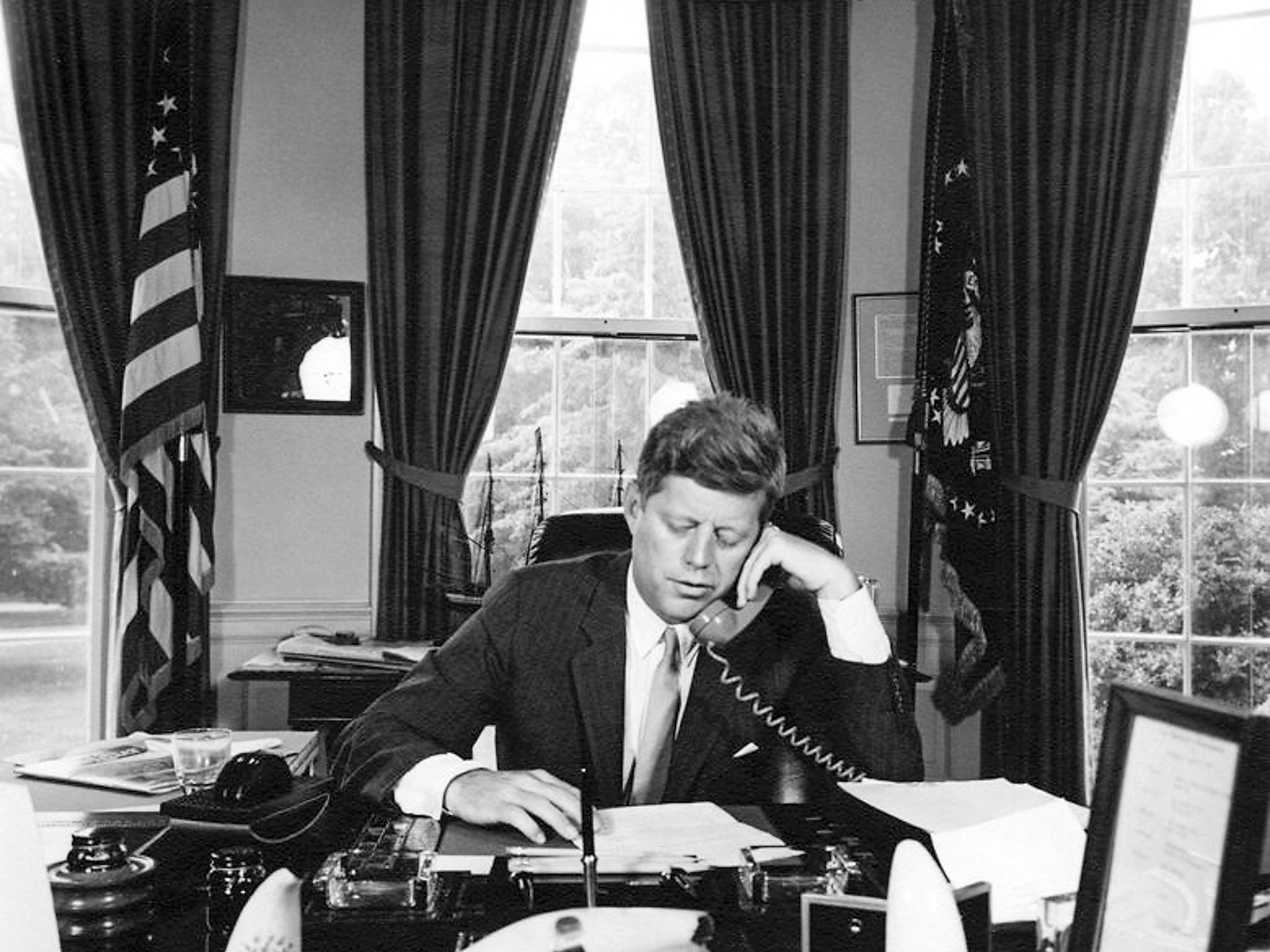

However, one must probe deeper to get to the bottom of the allure of JFK. Long before Ronald Reagan, he was the first movie star to occupy the Oval Office. Kennedy knew how to harness the youthful promise and vitality, the preternatural good looks, the inimitable Boston Irish Catholic accent, the radioactive charisma, the sartorial style and the wit demonstrated in sparring with the press.

And boy did the cameras love him for it, gazing adoringly at his visage. If ever there was a man for whom the phrase “women wanted him and men wanted to be him” had been designed, it was JFK.

Complementing him in equal measure was the elegant thoroughbred stock of Jacqueline Bouvier, whose contribution to burnishing the image cannot be underestimated. As JFK once quipped on a visit to Paris (and then in Dallas), he was merely the man accompanying Mrs Kennedy.

There was the deliberate cultivation of the pageantry of glamour swirling around America’s first royal family – for example, through Jackie’s White House dinners attended by writers, artists and entertainers. Kennedy understood the power of the image. One immediately thinks of the photo of Kennedy as President-elect arriving for Christmas mass with prayer book in hand at Palm Beach. The reality, divorced from the image, was the opposite of sober piety.

The Kennedys embodied the American dream: self-made Irish Catholic émigrés rising to become America’s foremost political dynasty. Most of all paterfamilias Joseph Kennedy whose money was made as a Wall Street and Hollywood mogul, the twin idols of the American dream (or twin Mammons, as the Tea Party would have it). The Kennedy image had mainlined into something deep in the American soul and she was hooked and hypnotised.

It was as if JFK had been born to be a statesman on the world stage. He appeared becalmed at the height of the Cuban missile crisis as the world teetered on the brink of nuclear war, his unflappability complemented by the unruffled quiff, the unperturbed features, the insouciant charm of a Cary Grant, all mirroring the smooth unassailable trajectory from war hero to Senator to President.

The press readily latched on to the idea of Kennedy’s cerebral nature and the intellectual dynamism of his inner coterie – an administration of “the best and the brightest”. Stories emerged of him speed reading à la Oscar Wilde. This was a ready-made photogenic media package. We now know that much of it was just that – spin. The kind of slick PR machine that our latter-day leaders can only dream of.

The White House tapes reveal Nixon’s candid assessment: “Kennedy was cold, impersonal, he treated his staff like dogs, particularly his secretaries and the others ... His staff created the impression of warm, sweet and nice to people, reads a lot of books, a philosopher, and all that sort of thing. That was a pure creation of mythology.”

We are really talking about what marketing gurus would term the JFK brand. Think of those sun-kissed images of Kennedy in shades sailing off Hyannis Port, or playing with his children in the Oval Office, or his daughter Caroline seated on his lap in Air Force One. These are images that advertisers would die for; today they are promoted by Gucci or Prada.

JFK was the original modern celebrity. It is as if every presidential campaign since has channelled this brand power and has merely been a cheap parody. It is surely no coincidence that Fellini’s La Dolce Vita came out in 1960, the year Kennedy was elected.

Think of the crowds throughout the Kennedy presidency that came out to greet him whether on the homecoming tour of Ireland or in Berlin or even on that day in Dallas. It was not only Americans who had drunk deep and been intoxicated with the heady swirl of the Kennedy myth. Those star-struck crowds would never reach the same fervour again. The promise and optimism of the Sixties would sour and curdle.

The symbolism of JFK’s “torch of liberty” lay in that he came to power during a period in which it seemed that the world might be changed for the better. This is the 'brief, shining moment' Jackie alludes to with her recollection of JFK listening to the musical Camelot in the evenings. The post-JFK era ushered in a politics in which adoration was replaced by the jaded cynicism that we are all too familiar with. Perhaps this was an inevitable by-product of the over-exposure of the information age and the penetrating tentacles of the mass media.

If Kennedy had lived, it is likely that he too may have been embroiled and scuppered by scandal perhaps as soon as the 1964 campaign. And we would not now look back fondly on or elevate him into the pantheon of great presidents (metaphorically carved into Mount Rushmore) but place him in the halls of infamy alongside Nixon – deformed and disfigured by political ambition like Richard III.

Even in modern times, the mega-wattage star power of JFK diminishes those not worthy of the legacy such as the Republican Vice President Dan Quayle in the 1988 election torpedoed by the comment “Senator, you’re no Jack Kennedy”. The stardust rubs off on any who are lucky to be close enough. The 1992 election campaign is now memorable for the moment when the young Clinton shook hands with his hero JFK in the White House rose garden. Obama’s 2008 campaign reached fever pitch following his papal endorsement by the last surviving brother – Teddy Kennedy – the greying, patrician statesman scarred by scandal, unlike his two slain younger brothers frozen for all eternity in their prime. The strategy of the Obama 2008 campaign, running on hope, was testament to the enduring influence of JFK.

In pictures: President Donald Trump on tour

Show all 39Yet Clinton would be smeared and nearly destroyed by the Lewinsky affair. It is remarkable to think of the gentlemanly agreement held by the newspaper men despite the lurid romps and indiscreet liaisons many of them taking place in the White House as Kennedy almost daily bedded escorts, starlets and celebrities. And the Obama presidency is a stark reminder of frustrated legislative programmes and of how perceived potential can fizzle out.

This brings us to the question of weighing up JFK’s achievements. The hyperbolic language of Greek tragedy did not seem out of place in the years that followed the assassination. For the circle of intimates (or what Gore Vidal might term acolytes and sycophants), such as Ted Sorensen and Arthur Schlesinger Jr, the modern age had produced one worthy of such description.

Jackie would prove to be equally adept at embellishing the legend from the state funeral modelled on Abraham Lincoln's cortège to constructing the Camelot myth. The lineaments of this tragic parabola from wartime heroics to peacetime leader to political murder were commensurate with such lofty sentiments. The lofty assessment of the early years would be lowered by more measured ones in later years. Yet even now, history’s verdict remains unsettled. As Zhou Enlai cryptically said of the French Revolution, it may be too early to say.

It is one of the great guessing games for those who partake in hypothetical histories of What If? What if Hitler had won the war? What if Kennedy had lived? Would his second term have seen civil rights legislation passed, pulling out of Vietnam and detente with the Soviets? Or would the Kennedy presidency over two terms have actually been remembered instead for one thing, the inevitable escalation in Vietnam? Would the chant of the campus protests have substituted JFK for “Hey, hey, LBJ how many kids did you kill today”? So hallowed and revered is the myth enshrining Kennedy that it seems unthinkable.

The Camelot myth was created by confidantes wishing to preserve JFK’s legacy. Contemporary historians should know better. One school of thought is exemplified by the likes of Oliver Stone. This attempts to recast JFK as a radical threat to the military-industrial complex. Yet far from being radical, JFK was a product of the establishment and a Cold warrior steeped in its rhetoric.

James W Douglass postulates in JFK and the Unspeakable that the Cuban missile crisis changed his perspective. Is it possible that a different Kennedy was emerging in 1963? One immediately thinks of the overtures of peace in the American University speech in Washington in which he spoke poignantly of our common humanity and reaching out to the Soviet Union. Or was this all merely soaring rhetoric that Kennedy had wielded from day one in the inauguration speech? This argument posits that JFK was beginning to contemplate cooperation in the space race instead of a nuclear arms race and even some kind of accommodation with Castro.

For every Oliver Stone eulogising what might have been, there is someone like Gore Vidal reminding us of what Seymour Hersh termed the “dark side of Camelot”: the allegations of vote-rigging in the 1960 election with Daddy buying the presidency; the “dirty” politicking; the supposed Mafia connections; and the relentless and unsavoury philandering. The closer we look the more JFK actually resembles the first Berlusconi.

Yet the posthumous revelations of Kennedy’s sexual magnetism have arguably enhanced rather than diminished his charismatic aura – one starlet described the single minute of presidential intercourse as the most exciting moment of her life. Admittedly, in another account of eloping with JFK, the most memorable detail is the unglamorous description of how long it took him to remove the strapping for his back. Despite decades of lurid revelations, there is something Teflon about the Kennedy brand. Most of it does not seem to stick. Perhaps it says something about how superficial we have become, enamoured rapturously by the image despite knowledge of the rot that lurks below the surface.

The towering figures of the American mid-century – Roosevelt and Eisenhower – dwarfed their successors. The real legacy of the Kennedy era may be the curtailment of the executive power of presidents. Eisenhower himself warned of the influence of the military-industrial complex (a term he coined) in his farewell speech. In the wake of the assassination, Harry Truman penned an opinion piece in The Washington Post on how the CIA had become too powerful, outgrowing its original remit of intelligence gathering by expanding into covert ops. LBJ may have barked at his advisers when they warned him not to pursue civil rights: “Well, what the hell is the presidency for?” Yet such presidential fiat has been steadily declining over the years.

Youssef El-Gingihy is the author of How to Dismantle the NHS in 10 Easy Steps, published by Zero books

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies