Super-hard Brexit: how UK planned to blow up the Channel Tunnel with a nuclear bomb

Civil servants acknowledged the atomic bomb plan could convert the tunnel into a mortar firing nuclear explosives into Kent and Calais, but reasoned it would be "100 per cent effective" at destroying our only physical link with France. It wasn't the first - or last - time that Channel tunnel plans showed how Britain's relationship with the rest of Europe has rarely been straightforward.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fear not, there is a plan.

After all the talk about Brexit means Brexit; hard Brexit; soft Brexit, red, white and blue Brexit, and now the triggering of Article 50, some might have been forgiven for wondering whether the British Government had a plan – any plan – for Brexit.

What exactly is the Government hoping to achieve from negotiations that have begun with Theresa May making veiled threats about withdrawing security cooperation? And, if after such a promising start things turned horribly sour, what are we going to do if our relationship with the rest of Europe breaks down irretrievably?

In fact, forget May, Brexit minister David Davis and our, err, trusty Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson: has any British government, ever, made any plans for a total break with Europe?

Well, it turns out they have.

In once secret files, now tucked away in the National Archives at Kew, The Independent has discovered the outlines of a cunning plan, drawn up by a succession of far-sighted civil servants and senior military officers, for a very hard, hard Brexit. It involves the option of blowing up the Channel Tunnel with a nuclear bomb, and not telling the French what we are up to.

There would, Ministry of Defence civil servants reasoned, be a certain amount of “collateral damage” to Kent (and less problematically to Pas-de-Calais).

But an atomic bomb would be “100 per cent effective” at ensuring a “totally irreversible total collapse, rupture [of] tunnel and sea bed to cause total flooding and complete collapse of part of tunnel”.

The main worry appears to have been the cost.

And keeping the plan secret from the French.

Because these were different times. The plan to sever our physical link with Europe was being made before the tunnel was built, at a time when it was feared that the “Barbarians at the gates of Calais” – to use one civil servant’s phrase – would not be “hordes” of immigrants, but an invading Soviet army.

Rather than making threats about security and leaving, we were trying to reassure everyone of our friendly intentions and join – and remain in – the European Community.

Hence those who drafted a letter from the Ministry of Defence to the Ministry of Transport in March 1969 advised that explosive demolition ideas “should be covert and classified not less than SECRET UK EYES ONLY”.

Because, they argued, would it really be acceptable: “For overt preparations to be made to destroy our only link with France and the remainder of the Continent … when the UK is endeavouring to become a member of the Common Market and to convince continental Europe that we have shed forever our island mindedness?”

Perhaps they should have known the bit about shedding forever our island mindedness was a bit of a folorn hope.

After all, the history of British thinking about the Channel Tunnel tends to read a lot like a singular demonstration of “island mindedness”.

From 1802 and Napoleon onwards, it is littered with fears about an island nation losing “her ancient moat defensive”.

If we weren’t immediately invaded, England’s “splendid isolation” would be corrupted by visiting foreigners with their foreign ways flooding in via the “murksome, ugly bore”, its roof “festooned with seaweed”.

We would become “abject landlubbers”, a disastrous reduction in national moral fibre being occasioned by a lack of exposure to the character-building ordeal of seasickness.

For as subscribers to the Spectator magazine protested when it was proposed that a tunnel might replace ferry crossings in 1929: “We Britons must be seadogs not earthworms” … “If a Britisher has not the grit to face one hour at sea, is he fit to belong to our island heritage?”

If nothing else, perhaps, it is a reminder – albeit not necessarily needed right now – that “our island heritage” has produced a relationship with Europe that has, shall we say, rarely been straightforward.

As demonstrated after Britain got the atomic bomb in 1952.

It seems we didn’t waste too much time in considering how best to use our new weapon to destroy any link with Europe.

The first reference found in the secret files to destruction using a nuclear bomb comes in November 1959, when a Channel Tunnel building project was being proposed and the Ministry of Defence advised: “Nuclear weapon development has rendered the proposed tunnel vulnerable throughout its length. Conversely, the tunnel could be totally destroyed for defensive purposes if necessary.”

Conventional explosives, you see, just weren’t destructive enough.

“The problem here,” explained MoD official Michael Legge in February 1974, “is that according to Channel Tunnel Group engineers, the tunnel would be virtually unscathed by an explosion of very great magnitude since the force of the explosion would be dissipated along the tunnel.”

“Pre-chambering above the roof of the tunnel,” he added, “Would make it possible to cause rock falls which would block the tunnel, but such blockages could be removed in a few days.”

By contrast, as made clear in an options paper which started at “cut off power” and got progressively more destructive, option 14, “total collapse” caused by explosion using atomic demolition munitions, would be 100 per cent effective at producing irreversible blockage.

There were drawbacks, admitted Mr Legge.

The atomic bomb plan could convert the Channel Tunnel into a 30-mile-long mortar firing nuclear explosives out of both ends.

“An atomic explosion in the tunnel,” explained Mr Legge to officials including a representative of the Secret Service, “Could have a ‘mortar’ effect and cause widespread damage at the portals [of the tunnel] and in the surrounding area.”

The words “civilian casualties” do not appear in the minutes for that January 1974 meeting, but on the copy of the agenda that survives in the National Archives, someone has scribbled: “What about collateral damage”?

Mr Legge also appeared most concerned about the issue of cost.

In a February 1974 briefing paper he warned: “I am not sure if we possess an appropriate weapon, and if we could produce one at acceptable cost.”

And, he wondered, could such extravagant expenditure on an anti-Channel Tunnel nuclear bomb really be justified, given that if the tanks of the communist Warsaw Pact got as far as Calais, it was pretty much game over anyway?

“Frankly,” wrote Mr Legge, “If we ever reach a situation where Warsaw Pact conventional forces reach Calais without a strategic nuclear exchange having occurred, then I think the Channel Tunnel will be an irrelevance.

“Warsaw Pact air and maritime superiority should by then be adequate for invasion by other means.

“I am putting down a marker that we [the MoD] may eventually be asked to meet any extra cost incurred during construction.”

At least everyone was agreed that we shouldn’t tell the French.

The unanimous view was succinctly expressed in 1969 by Brigadier John Constant, head of the Channel Tunnel Engineering Division at the Ministry of Transport, a man seasoned by wartime service as a sapper in the Western Desert and Burma.

“My proposal is that the Anglo-French requirement will not include any built-in demolition arrangements, but that a nominated representative of MoD be appointed to examine our plans in secret.”

In the very next sentence, he gleefully told his friend on the Chiefs of Staff Committee: “You may recall that a previous Channel Tunnel plan included an exposed section at the French coast, so that it could be bombarded by the Royal Navy when so inclined!”

In fairness to the brigadier, his attitudes were probably far more advanced than those that had prevailed among military men for most of the previous 167 years.

Ever since a Channel Tunnel was first proposed in 1802, it had been – as the Department of Transport acknowledged in 1971 – “haunted by the spectre of foreign Dragoons galloping out of the ground in Kent”.

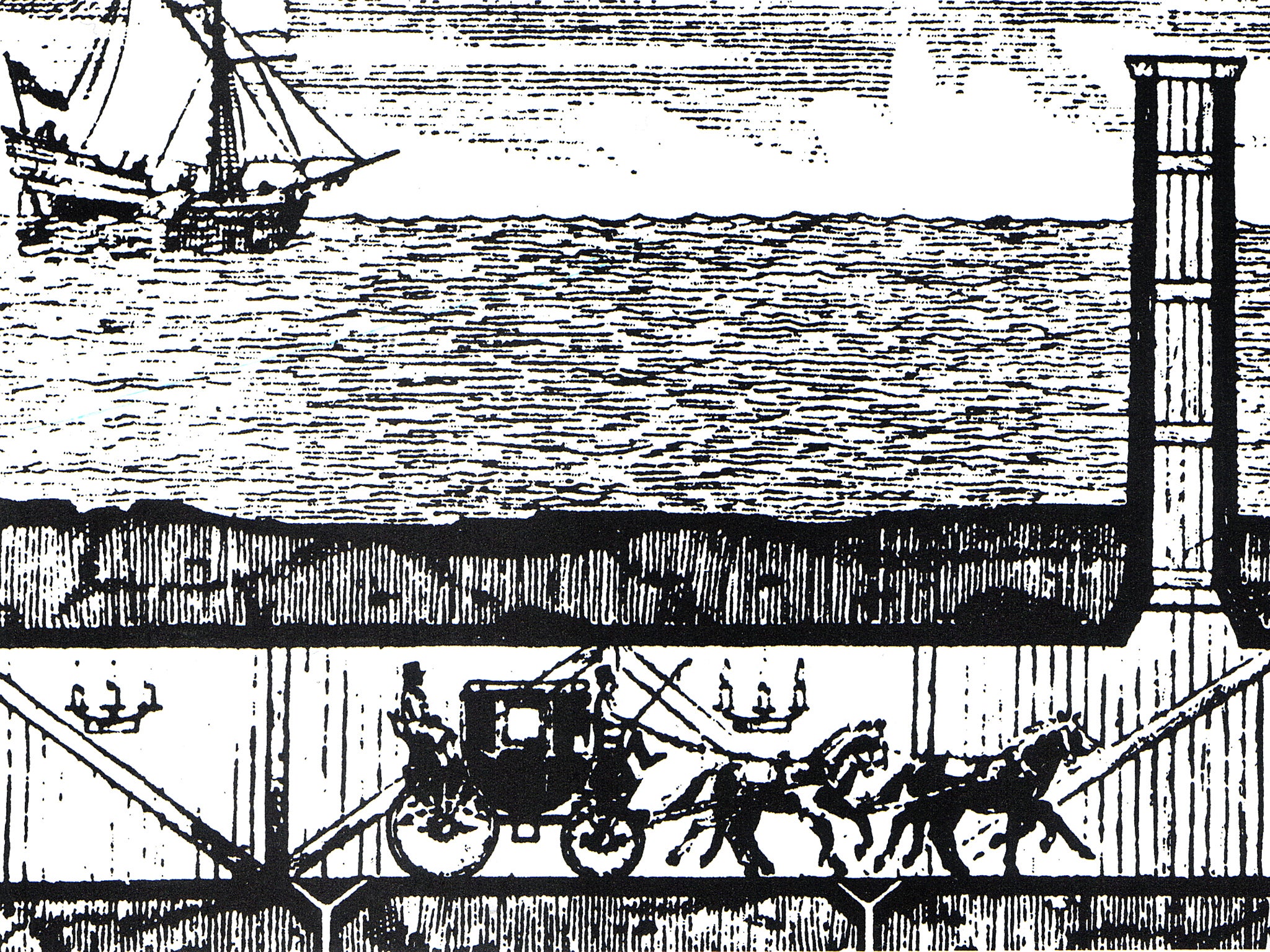

The first idea, from French engineer Albert Mathieu-Favier, for a candlelit tunnel used by horse-drawn vehicles, was scuppered by the invasion fear created by the antics of Napoleon.

Britain declared war on France in 1803 – partly because we felt insulted that Napoleon had suggested we deserved no voice in European affairs.

Emperor Napoleon III – Bonaparte’s nephew and heir – found more favour when he enthusiastically endorsed another Channel Tunnel proposal in 1865. Queen Victoria was keen, because she tended to get seasick.

Unfortunately, the government of the day was led by Lord Palmerston, a man fonder of gunboats than tunnels, and not known to suffer from seasickness.

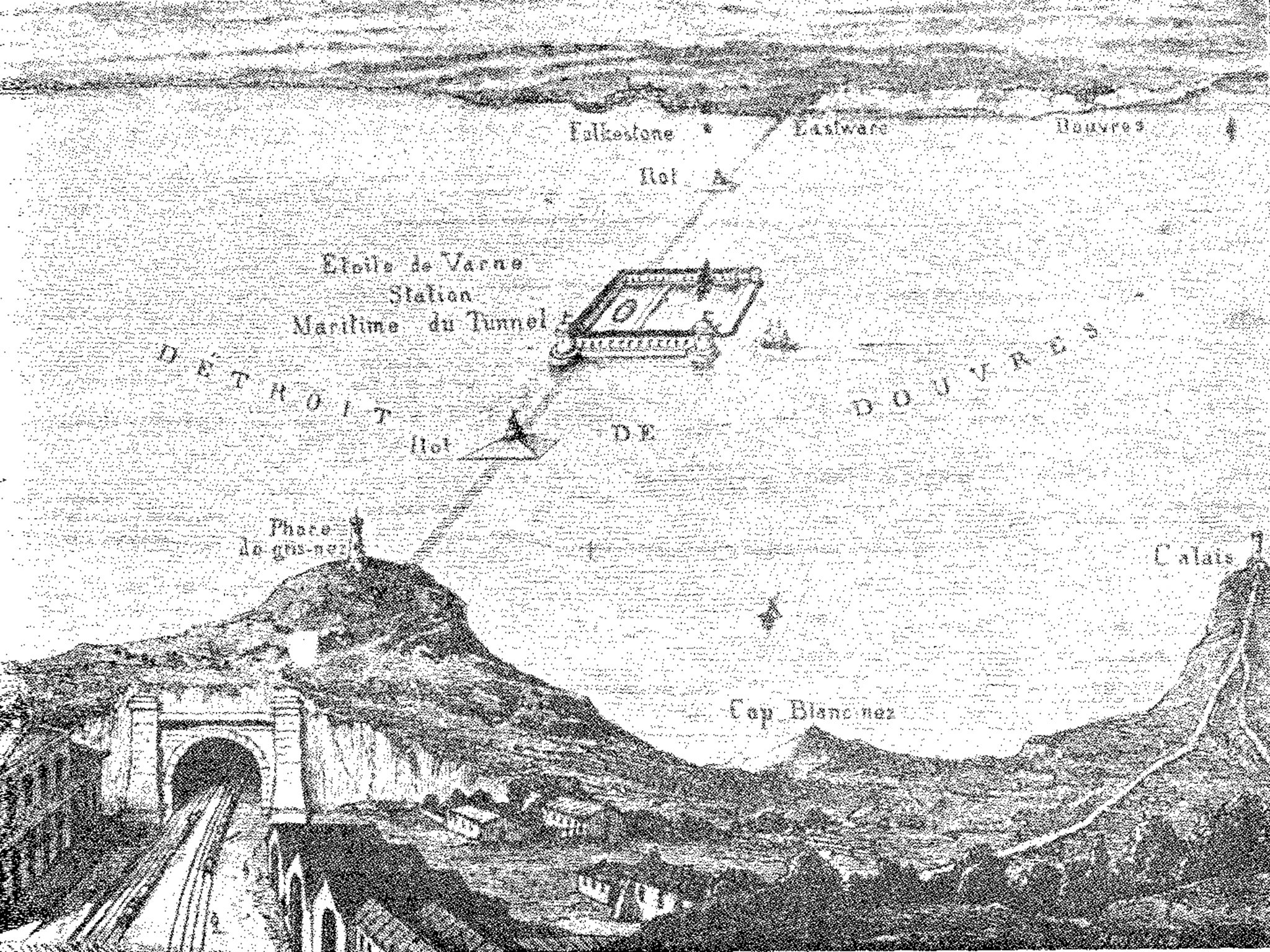

Then in 1882, Sir Edward Watkin’s Submarine Continental Railway Company announced that using Captain Thomas English’s marvellous new boring machine, they could dig to Calais by 1886.

Cue “a great ferment”, as Prime Minister William Gladstone called it.

At this stage in British history, it seems, the liberal metropolitan elite was implacably opposed to closer ties with Europe. A 1,070-signature petition against the tunnel was signed by everyone from Queen Victoria’s gynaecologist to the Archbishop of Canterbury via Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

Gladstone blamed “public opinion manufactured in London by great editors, and clubs … backed by the military and literary authorities and the social circles of London”.

He stood little chance against the hero of the hour, Lieutenant General Sir Garnet Wolseley, fresh returned from his triumph against Urabi Pasha at the Battle of Tel el-Kebir, who warned a military commission the tunnel would be “calamitous for England”.

The French or whoever held Calais “could by a coup de main seize our end of the tunnel,” he wrote. “Dover would become a tête de point, from which they could issue forth with any large army they chose to bring through the tunnel. From that moment, we would cease to be an independent power.”

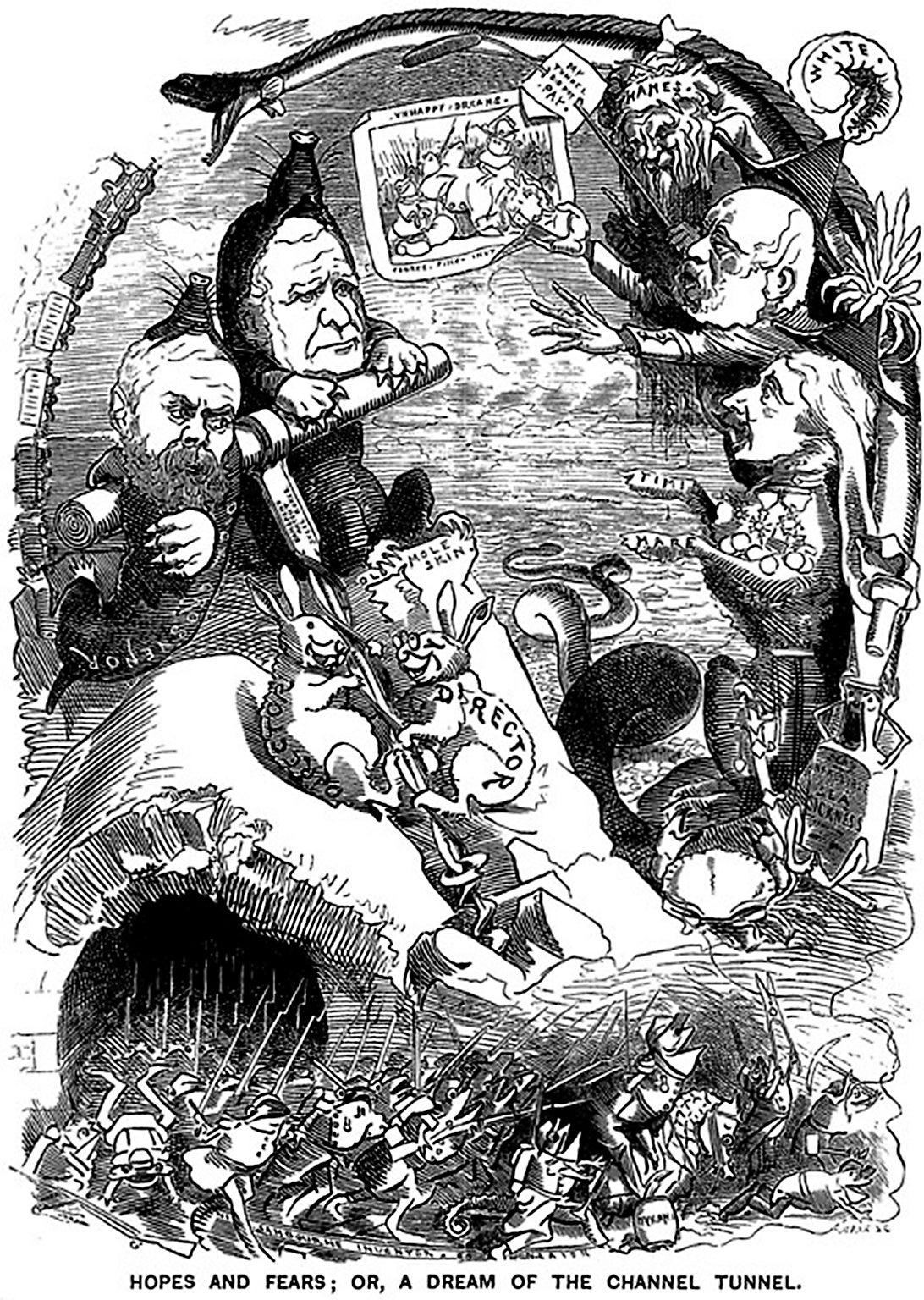

The resulting national mood was summed up by a cartoon in Punch magazine. It showed an invading army

rushing from the mouth of a tunnel drawn to resemble an all-devouring snake. Readers who looked closely enough saw that every soldier was an armour-clad frog.

By the time a Channel tunnel was again mooted in 1929, the military had devised further objections. A retired admiral informed the press that a tunnel would lead to a decline in the British seafaring industry, with skilled seamen lost to unemployment.

In time of war, instead of being able to call upon a ready pool of “100,000 men who are not subject to seasickness”, the Navy would have “abject landlubbers who must be trained in seamanship and get their sea legs before they ever try gunnery”.

It wasn’t just the military men who were worried.

“The doctrine of England’s ‘splendid isolation’ was cited in some quarters,” wrote the correspondent of the American magazine Popular Mechanics, “And the fear expressed that quick and comfortable train journeys [through the tunnel] would make England a holiday resort for hordes of more or less undesirable people, who would introduce foreign customs, deface the countryside and otherwise interrupt English habits of living.”

The Spectator magazine of February 1929 duly noted “the rather misty argument that no one knows what changes our national psychology would undergo were we materially linked to the Continent”.

“The most passionate appeals,” it added, “are from the hearts of those who feel themselves descendants of a proud seafaring race.”

One subscriber vowed never to swap the fresh sea breezes on a boat for “something damp and stuffy, with water trickling down the sides, and a roof festooned with seaweed”.

And Miss F. M. Griffiths, of Harborne Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham, won a five-guinea prize for “her entertaining poem” invoking Britannia and condemning:

“Such treason to Sentiment, to History and Tradition.

“Consider the impossible position

“Of the wandering patriot: Can his heart within him burn

“As his footsteps homeward turn,

“… Through a darksome, murksome, irksome, ugly bore?

“Can his manly bosom swell (As it ought to) crossing over,

“At the first soul-stirring sight Of the dear white cliffs of Dover;

“Why traitorously burrow

'"Neath her ancient moat defensive,

“And force the dame to barter

“Her trident for a spade?

“A trident that has made

“Our fiercest foes afraid

“And our Empire so extensive.”

The 1929 plan was shelved.

It wasn’t until 1949 that the senior officers came round to the view that, actually, a Channel Tunnel might be militarily advantageous.

With the Cold War starting, they decided a tunnel could be of assistance in getting reinforcements as swiftly as possible to the British Army on the Rhine in the event of a Soviet attack – although they insisted that if we wanted a Channel tunnel, we needed a foolproof way of destroying it.

Thereafter objections from military figures tended to be of the more esoteric kind. In October 1968 retired Group Captain Eugene Vielle, former director of operational requirement at the Air Ministry, now a thriller writer, contacted The Times to warn about the newly proved theory of continental drift.

“Vielle,” The Times reported, “suggests the continent of Europe and Britain are imperceptibly drifting apart. Even a fraction of an inch might be enough to fracture the tunnel and flood it.”

Geologists, though, were sceptical and, as The Times hinted, Vielle may have been a bit biased: “He has disliked tunnels ever since being stuck in the Simplon [between Switzerland and Italy] in the dark with a car load of frightened children.”

The atomic bomb plan, though, got overtaken by events.

In January 1975 Harold Wilson’s Environment Secretary Anthony Crosland announced that the Government was shelving the Channel Tunnel project because of its high cost.

With the 1975 EU referendum just months away, the Labour minister was immediately accused by an enthusiastic pro-European, the Conservative MP and later Thatcher minister Paul Channon, of “a decision that has been maliciously taken by the anti-Europeans and left wing in the Government”.

By that point, it seems the desire for 100 per cent destruction offered by an atomic bomb had lost out to anxieties about unintentionally firing a nuclear mortar into Kent, at vast expense.

In possibly his final word on the matter, in a letter of June 1974 to the Department of the Environment, Mr Legge of the MoD expresses the “preliminary view” that long-term tunnel destruction might best be accomplished by less explosive methods: “creating blockages by head-on train crashes” or “flooding by pumps or inbuilt scuttling devices”.

But if the more ardent Brexiteer should feel any disappointment about the extinction of plans to nuke the Channel Tunnel, they can at least take comfort in the thought that the flooding plan had the perfect patriotic pedigree.

As the flooding idea gained favour in Whitehall in the 1970s, MoD officials passed each other a copy of the secret note written in June 1914 by the First Lord of the Admiralty.

“WSC,” the officials told each other admiringly, “was only 60 years ahead of his time.”

Because in June 1914, Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, had advised: “Means of flooding the tunnel should be provided.”

The mouth of the tunnel should be at sea, he added, with the final connection to the shore being via a rail bridge, complete with a drawbridge in one of its spans.

“In strained relations, or on any sign of danger, the lifting of the drawbridge would afford absolute security, and the flooding of the tunnel could be considered at leisure.”

And “If by treachery the drawbridge was rendered inoperative, the guns of a single small cruiser could break down the bridge and absolutely prevent the passage of trains or troops by night and day.”

So now we know: if Article 50 negotiations fail, if Brexit must be hard, we can do it Winston’s way, with a raised drawbridge, a flooded tunnel and the perfect moat defensive.

After all, with the will of the people so strongly expressed by the Brexit vote, who can quibble about a few structural modifications to the tunnel that opened in 1994?

Asked whether the building of the current Channel Tunnel involved plans for disabling it in the event of an invasion, a Eurotunnel spokesman said: “There has always been a military aspect to it, but I cannot give any further insight into what plans may or may not exist.”

The Ministry of Defence was contacted for comment. When The Independent asked whether current options included a nuclear bomb, the response was prolonged laughter. It seemed genuine.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments