The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

The brain drain and youth depression taking over Greece

As Greece’s financial struggle from the crash continues to worsen, Theresa May warns that failure to tackle the UK's deficit could see it spiral into a ‘Greek-style scenario’. Chloe Farand meets the young and old Greeks who are worse affected by the lack of jobs and cut to pensions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Many people in this village live off a plot of land in the winter because there just aren’t any jobs here,” says a mother of two. The situation in Greece is worse now than it has ever been before,” says a mother of two, who insisted we try some of her perfectly ripe homegrown apricots.

She runs a simple cafe in the small village of Mesopotamos on the north-west coast of Greece. Located six miles away from the beach, business is good in the summer months thanks to tourism, but winters are tough for her and her family.

Inside the cafe her 17-year-old daughter serves ice coffees and cool beers. Her mother is grateful for her help but she says her daughter is talking about going abroad to study because there are no opportunities for her in Greece. A whole generation of Greek children are growing up knowing they will have to leave their home to seek opportunities and work in other countries.

The past seven years of crushing austerity and recession have caused rocketing levels of youth unemployment, where a suffocating atmosphere is fuelling depression among many young people. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), unemployment among 18 to 24-year-olds reached 47.4 per cent at the end of last year. Overall, more than one in five Greeks were unemployed.

In the workplace, long hours, low pay, and a lack of jobs suitable for graduates has become the norm. Athens resident Odysseas, 24, has a master’s degree in European and international affairs, and works in a thinktank but says many of his friends work more than 12 hours day with no overtime. He adds more young people are taking on undeclared work and has become disillusioned about what Greece can offer him.

“The truth is that young Greeks are growing up with the idea that they will have to leave. This is not an exception but the pattern. I am part of that brain drain,” he says. He is leaving for Paris in September to study a second master’s degree. “Most of my friends also want to go and work or study abroad because youth unemployment is at its highest level in Greek contemporary history. It’s creating a suffocating environment for young people who do not have the opportunity to get a job here,” he says.

There is a sense among many Greeks that accumulated austerity has left them worse off now than ever before. And despite rising poverty and a deepening social crisis, Greece has largely dropped off the news agenda in the rest of Europe.

Last week, Theresa May defended Greece’s government’s austerity agenda and warned parliament that failure to tackle the deficit could see the UK spiral down into a Greek-style scenario – a shortcut for a deep economic, social and political crisis.

Despite slow signs of economic recovery, Greece is now on its knees. Capital control continues to limit the amount of cash people can take out of their own bank accounts to about €400 (£353) a month – making it particularly difficult for households with shared accounts. The older generations, whose pensions once formed a lifeline for younger family members, are now unable to support their children and grandchildren after pensions were cut 12 times in recent years.

On the outskirts of Athens, in the industrial town of Elefsina, Tasos Koropoulis, 65, struggles to see what good has come of EU-driven austerity measures. Koropoulis, a proud communist who keeps a statue of Lenin on his mantelpiece, is bitterly disappointed with left-wing Alexis Tsipras’s time in office. He worked in a cement factory for 40 years and remains to this day an active union member. The grandfather of three is nostalgic for an old way of life when the industrial heart of the city was a major source of employment for the area.

Pointing out to a row of empty looking factories on the side of the road, he says: “Here they used to employ 600 people, now 50 work there... here it was 1,000 now there are about 100 and here they used to be 2,000 staff, now it’s just about 600.”

Koropoulis used to be able to help his two sons, who both work in the hospitality trade, and use his pension money to treat his grandchildren. But those times have gone too. Now 43 per cent of Greek pensioners now live on an average of €660 (£580) a month after tax with many still supporting their family, according to Lucas Juan Manuel Alsonso, from London School of Economics (LSE). In comparison, pensioners in the UK have an average £296 a week after deducting tax and housing costs, according to the latest figures from the Department for Work and Pensions.

For Koropoulis, the end of the crisis is not in sight and he is concerned about what opportunities there will be for his grandchildren growing up. “I think it will be 2060 before this crisis is solved. I will be dead and you will be old,” he tells me.

Zoe Kostitsi-Papastathopoulou’s family lives in Giannitsa, a city in the north-west of Thessaloniki. She says until 2012 there were no obvious signs of an economic downturn in the rural areas because strong family links acted as a safety net. “Young people used to live off the pensions of their grandparents. Families links are very strong in Greece and so everybody would share an income as part of a same family,” she says.

But as taxes multiplied, salaries were slashed and pensions took the hit, the traditional support network started to crumble. As time went on, Kostitsi-Papastathopoulou, who works for a migration NGO in Athens, says signs of poverty started to become more visible in everyday life. Remembering a trip to Athens in 2015, she says: “I was shocked because I was seeing a country that was experiencing real poverty and homelessness like I had never seen here before.”

Between 2008 and 2015, levels of poverty rocketed by 40 per cent, according to a study by the Cologne Institute of Economic Research. Last year Eurostat found that more than one in three Greeks were experiencing conditions of poverty or social exclusion, including 37.8 per cent of children aged under 17, the highest percentage in the EU since 2010.

“People are gloomy and divided – they are afraid of the future,” says Kostitsi-Papastathopoulou. “People are losing hope because they are not seeing any changes or anything getting better.”

Greece has reached “rock bottom”, according to Sir Christopher Pissarides, regius professor of economics at LSE and a founding member of the Greek Economists for Reform, which provides leading commentary on the crisis.

“People are right to say the situation has never been so bad. People despair because they cannot see the end of it. We have been pushed and pushed down and if there is light at the top it has not yet, in practice, improved people’s situation,” he says.

Another €8.5bn (£7.5bn) of new loans were agreed last month by the eurozone to prevent Greece from defaulting on its bailout repayments. Athens still has to repay its creditors and in May, parliament voted through a further €4.7bn (£4.2bn) of cuts to be rolled out between 2018 and 2021.

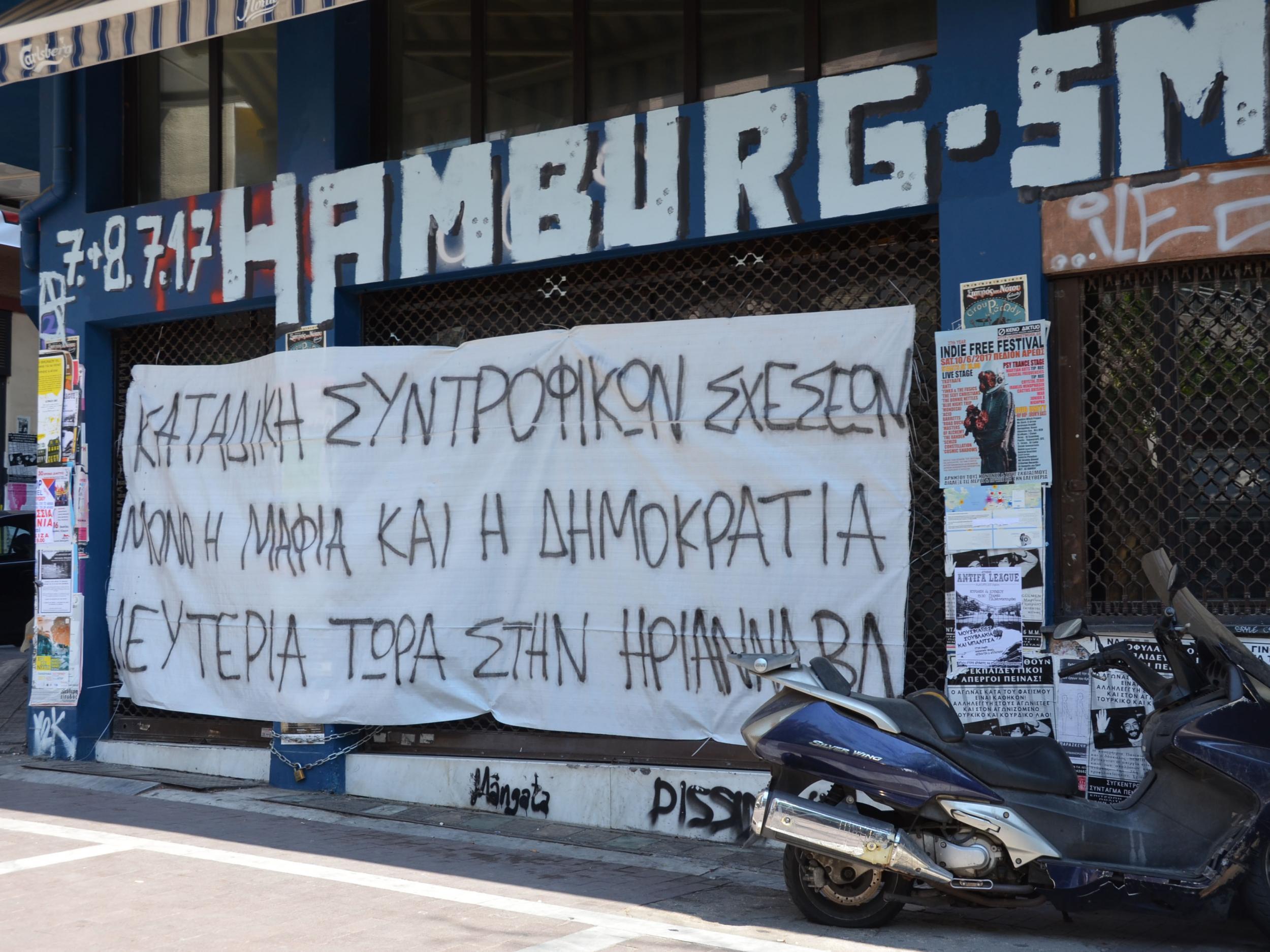

Through the spring, anti-austerity protesters marched through Athens and Thessaloniki but their chants are getting quieter and the crowds are getting smaller. Austerity has crept into daily life to become part of normality.

“Since 2009, the economy has been reducing non-stop. Greece was living above its means even before the financial crash. The crisis was unavoidable but it didn’t have to last for so long,” says Dimitri Vayanos, professor of finance at the LSE, also a member of the Greek Economists for Reforms. Vayanos argues that by the end of 2014, there were signs the economy was picking up, but following the election of Prime Minster Alexis Tsipras from the anti-austerity Syriza party, new negotiations with the EU and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) saw renewed austerity measures and a second crisis.

In Athens and elsewhere, people had to become creative in finding solutions to survive a second wave of recession. Yiannis, a 28-year-old project manager for an IT company in Athens, says universities are now becoming self-proclaimed startup incubators as students increasingly make plans to start their own businesses.

“Unemployment is causing depression among young people but they have learned how to pull together. They are now creating their own jobs by starting small businesses such as cafes or shops. Even three or five years ago, no one was speaking about start-ups but now there is a small ecosystem where people can meet and find funding options.”

The Greeks have blamed two main parties for letting the crisis spiral down: its own politicians and the EU. Since 2010 Greece has had six prime ministers and the lack of political stability did not inspire confidence among people.

The election of Tsipras came with a wave of hope that took the country in 2015. But the Syriza leader’s desire to change not only his country but also the EU was quickly confronted with Brussels’ rigidity. Hopes were dashed and eventually Tsipras was forced to bend to the troika’s (European Commission, European Central Bank and IMF) demands for more austerity.

On the other hand, there is a resurgent anti-Berlin feeling in Greece with many blaming Angela Merkel and her finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble for the EU’s unyielding stance towards Athens’ plea to ease austerity.

But if the EU has bad press, Grexit seems to have come off the political agenda. Some continue to argue for the return of the drachma, Greece’s pre-euro currency, but most economists agree that would be a devastating move for a small country attracting hardly any foreign investment.

But there are visible examples of how the EU has helped Greece over the years. The Egnatia motorway is an old Roman road, which runs 415 miles from the Turkish border in the east through spectacular mountain scenery to the western port city of Igoumenitsa. The €6bn (£5.3bn) road was completed in 2009 and boasts a series of 173 bridges and 73 tunnels – a major infrastructure project which would have never seen the light without EU funds.

Professors Pissarides and Vayanos, however, say the tables may have started to turn. In a statement on Wednesday, the European Commission recommended ending deficit measures against Greece.

The Commission said it recognised Greece’s “substantial efforts in recent years… to consolidate its public finances” in a move which showed the EU’s confidence in the country’s ability to progress on the road of economic recovery. This comes as Greece’s deficit has improved from 15.1 per cent in 2009 to a surplus of 0.7 per cent in 2016 – below the threshold imposed by the EU.

Pierre Moscovici, EU commissioner for economic and financial affairs, describes the decision as “a symbolic moment for Greece” that followed “years of sacrifices”, adding: “Greece is now ready to exit the Excessive Deficit Procedure, turn the page on austerity and open a new chapter of growth, investment and employment. The Commission will remain at the Greek people's side during this new phase.”

Meanwhile, the election of French President Emmanuel Macron, who has repeatedly said he is in favour of debt relief for Greece, also came as a beacon of hope. A staunch European, Macron wants to boost the European project, but the question remains whether he will be able to wield influence over Germany, the single biggest contributor to the Greek bailout.

Although many Greeks have the impression of living under Brussels and Merkel’s diktat, Greece continues to have deep connections with the EU. Hundreds of thousands of European tourists travel every year to its beautiful Mediterranean beaches and the Greek islands live in a separate economic microcosm from the mainland.

As holidaymakers arrive in cruise ships and shuttle boats from Athens’ port, migrants climb out of rubber dinghies to reach Europe’s shores. Kostitsi-Papastathopoulou admits the migrant crisis created scores of jobs from field workers organising logistics to doctors and psychiatrists, at a time when the Greeks needed them the most.

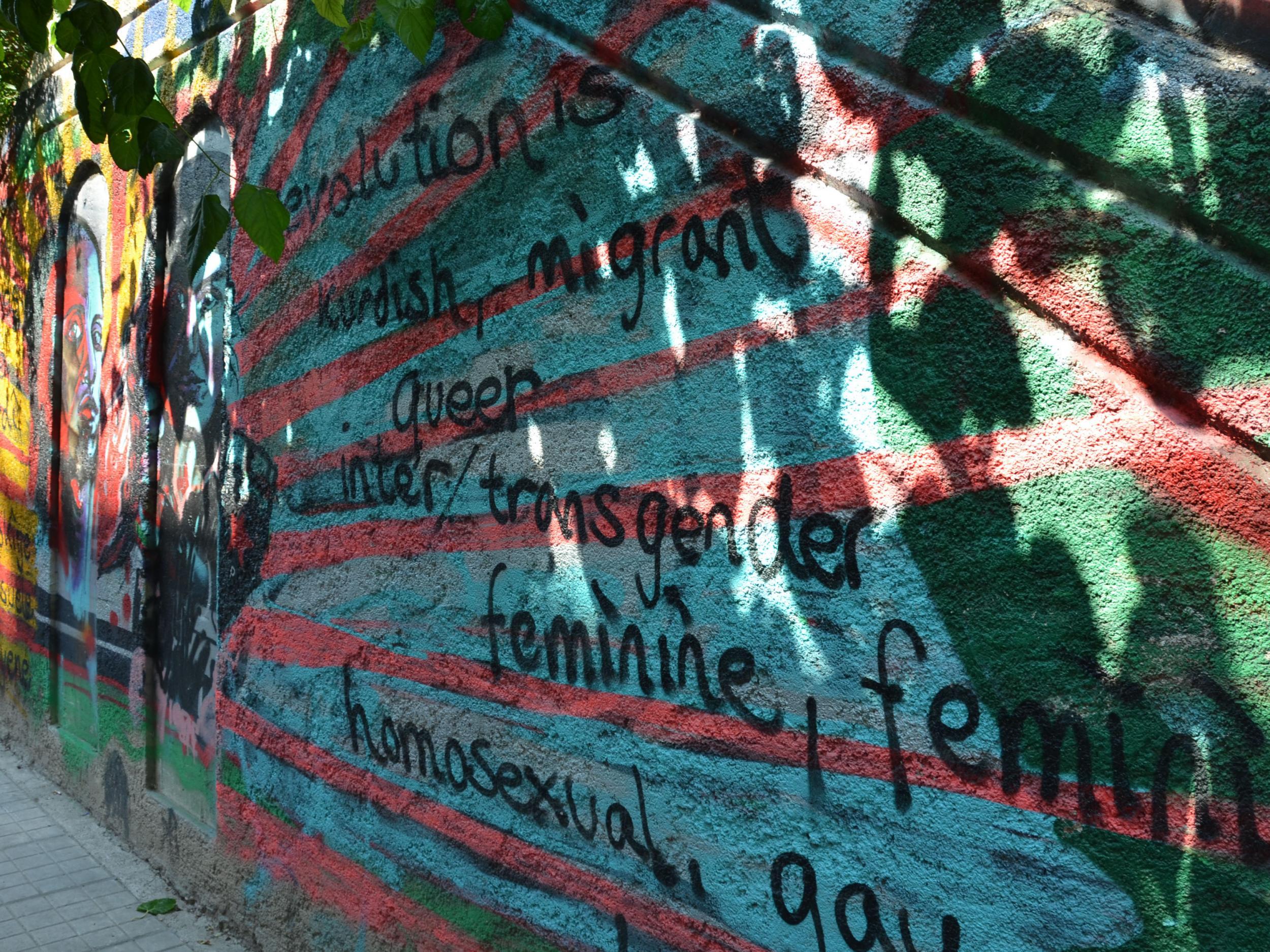

In the anarchist district of Exarcheia, a self-organised community lives in abandoned buildings and squats. Behind the walls covered in political murals and street art, volunteers give refugees classes and collectives for an alternative form of social and political engagement thrive.

Believing that things can only get better, Yiannis says: “People here have to help each other – this is how we survive the crisis. If you look back at Greek history, there has always been a war or a crisis and people have always pulled themselves out of it.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments