Glass buildings are not energy efficient or fit for purpose, explains architect?

Old fashioned and bigoted environmental determinism gave us glass buildings – and all the energy problems associated with them. Alan Short explains how we got to this sorry state and what we should be building instead

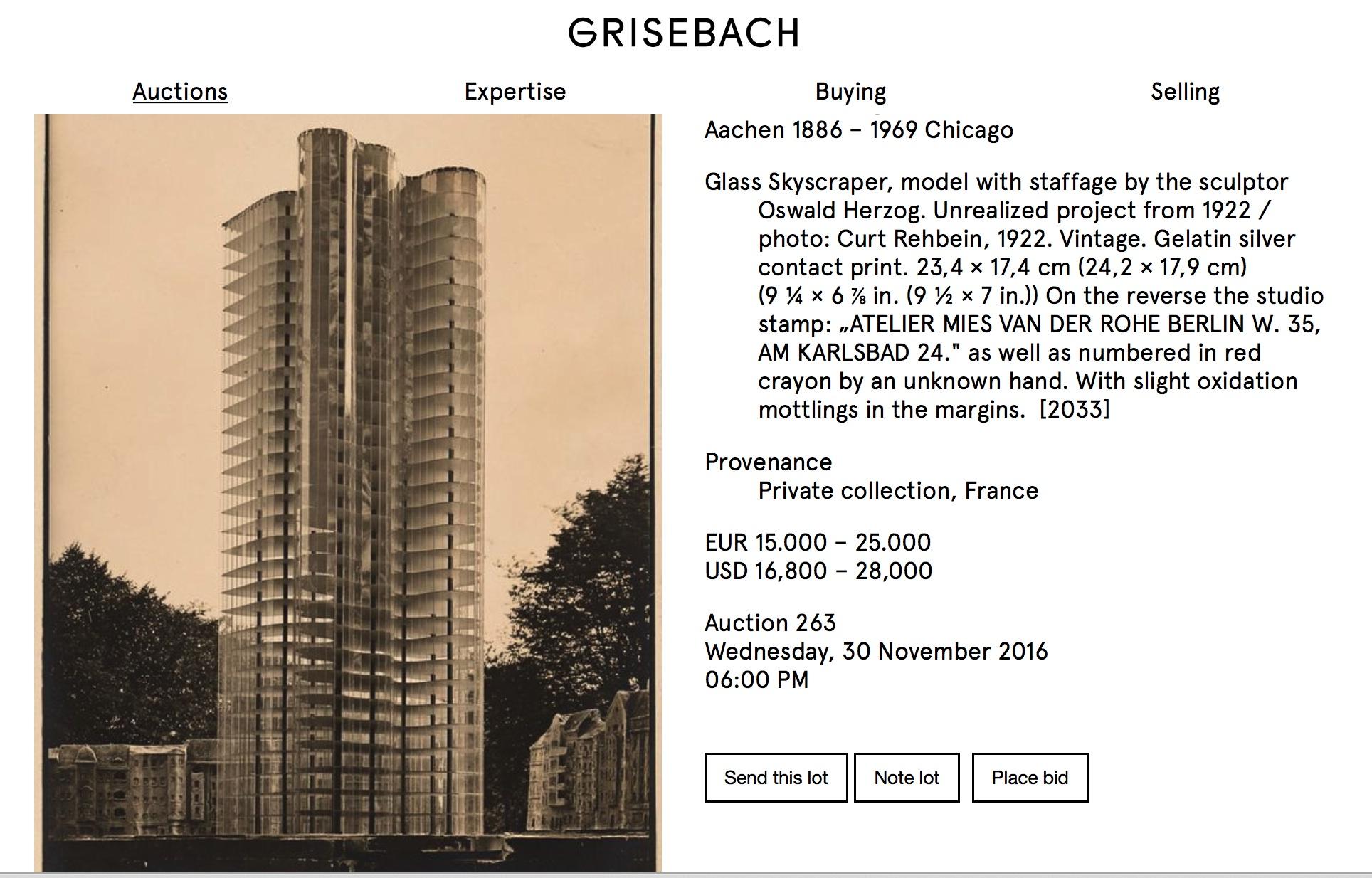

A year ago the German auctioneer Grisebach included one of the most iconic architectural images of the modern era, a 1922 gelatin silver contact print of a model of one of the very first glass office towers, Mies van der Rohe’s design for the 1919 Friedrichstrasse office building competition. It rises out of a decrepit clay city.

The first version was angular but the second, as modelled by the sculptor Oswald Herzog, wrapped a sinuous glass facade around double height floors. Both were intended to persuade the guardians of the Prussian Building Regulations that the statutory minimum natural light level would be provided at the back of the illegally deep plan. Mies van der Rohe was cheating. The tactic didn’t work, no one knew how to make it, but within two decades the model had jolted commercial architecture on to a very different track.

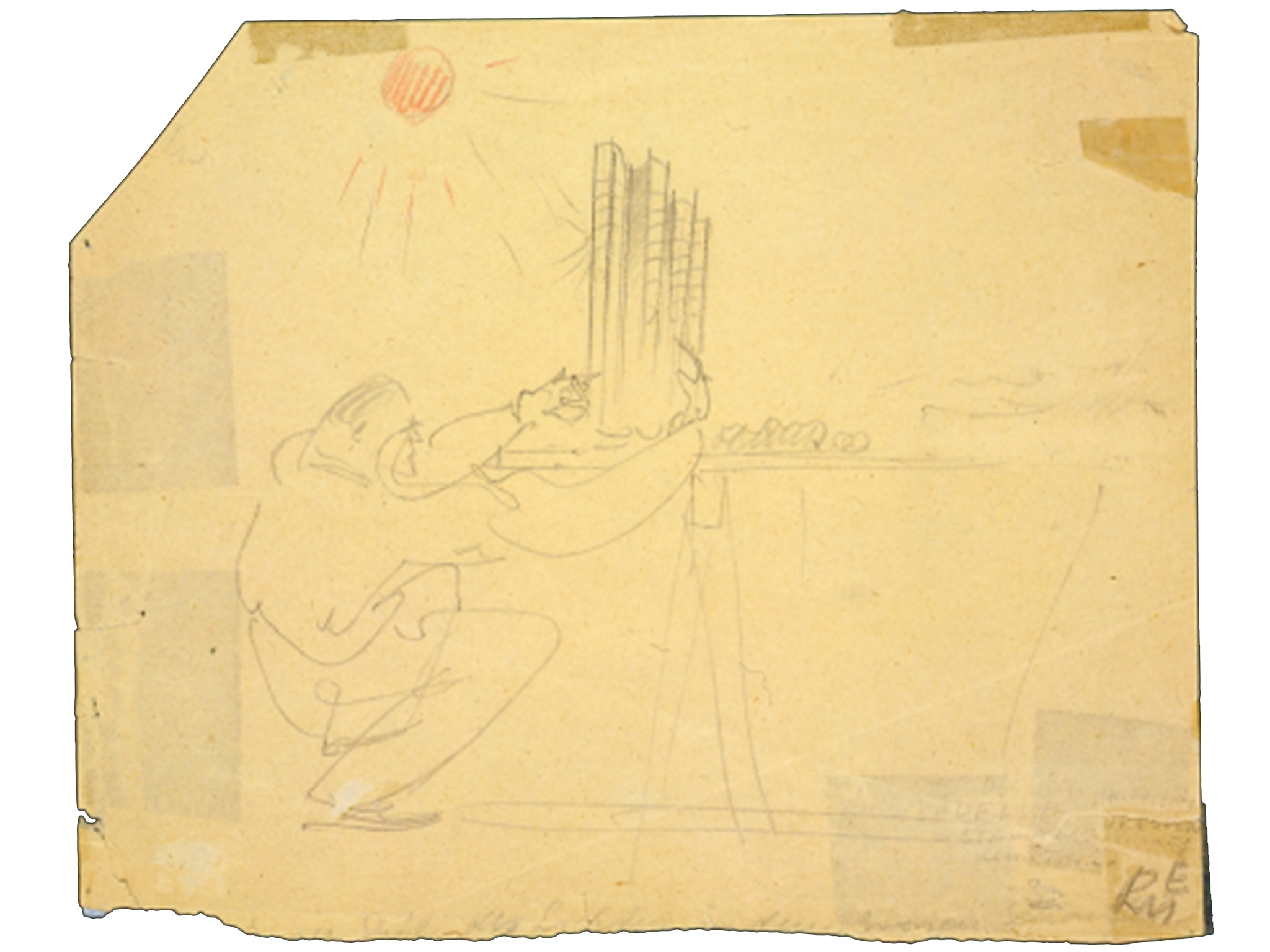

Van der Rohe crouching in front of his model in rapture at the unexpected reflections was sketched surreptitiously by a student visiting his office, Sergius Ruegenberg. The spirit in which the sketch was undertaken is unclear but it is difficult not to notice that he has drawn the sun beating down on the transparent model. In fact he has taken an orange crayon and coloured the sun as a burning disc. Could he see that the floors behind the thin glass envelope and the unfortunates within them would boil in a Berlin summer?

In terms of keeping it up, Van der Rohe's contemporary Mart Stam published a sketch of unfeasibly slender pencil columns propping up ultra thin concrete slabs in a 1925 edition of his journal ABC Beitrage zum Bauen. But there was no plan for making the tower inhabitable through a Berlin summer. Huge amounts of energy would have been required to refrigerate it by driving the technology of “artificial weather” being devised across the Atlantic at that very moment.

The Cornell entrepreneur, Willis Carrier, had invented the key ingredient, the “centrifugal condenser”, in 1922, enabling the massive air conditioning installations which followed. Architects could now play with just such absurdly insubstantial facades, cling film in effect, even in the very hot and very cold continental climates of Berlin, Chicago and Beijing.

Real estate advertisements in the Chicago Institute of Art archives show that prospective glass office buildings were already being promoted in Chicago after the Fire, majoring on the natural light flooding the narrow floors and therefore an end to spitting oil and gas lamps raining down soot on the well-pressed clothes of the new breed of administrators below.

But Van der Rohe's model was, and still is, mesmerising. Who could have imagined that a high-risk, left-field tactic for winning one of the very few commercial commissions in Berlin after the Armistice would launch an image that would infect global architectural production until today?

Its clinical aesthetic had “crystallised” in an environment of hallucinatory glassy thinking, the poet Paul Scheerbart’s hundred or so snippets of text under the umbrella of “Glasarchitektur”, which describe an imaginary world constructed entirely in glass. His circle, including the architect Bruno Taut, fantasised about the Backsteinbakillus, a fictional microbe that thrived in damp tenement brickwork, a throwback to the fear-inducing fomites and miasmas before germ theory became established.

The microbe’s name evoked the mediaeval brick architecture of the Hanseatic ports for greater ironic effect, making it clear that the past was bad for you. The complexity and cruel humour of Scheerbart’s Berliner world view is so powerful it survives translation. My Berliner mother’s very funny but uncomfortable observations during school appearances peppered my childhood and even a 13-year-old could tell they were just too much for English sensibilities.

Scheerbart’s 1914 novel, The Gray Cloth and Ten Percent White: A Ladies Novel, is certainly not propogandising glass architecture as one might have been led to believe. Newly married to Clara, the central character Edgar Krug, a priggish Swiss architect, travels the world in a Zeppelin attempting to bamboozle mayors and even whole nations to invest in vast structures entirely built of coloured glass. His condition for marriage is that Clara only ever wears a particular shade of grey so as to not despoil his glass interiors.

Clara’s friends are openly hostile. Does Krug exhibit a compulsive condition and does the imposition of the dress fulfil a tension-releasing role appearing within each new ultra-clean clean glass scheme? Clara is skeptical. Hovering above the Pole in the airship she writes to her friend Miss Amanda: “God only knows why Edgar still wants to have glass architecture here. I do not know. Indeed!” Her husband’s fame is such that a film is made of their lives, and she watches in horror as the actress portraying her delivers the line: “I am prepared to wear grey clothing for my entire life. I am doing this because I love glass architecture so much that I would never wish to create competition with a colourful outfit.”

It is only too possible that Scheerbart’s Anglophile disciples have been had for breakfast for decades with unanticipated but incalculable consequences globally.

Sadly, and we have invested a lot of time in this here, glass towers, even with elaborate doppel-fasades, can only work with a lot of artificial weather-making inside. A recent paper by Mingotti (2011) on the fundamental physics of double glass facades, the fanciest variant, shows that in Moscow, as in many other locations and climates, there are fundamental problems with the idea when the various energy balances are calculated.

Childlike promises of political transparency out of the physical transparency and passive solar collection are phantasms. The sight of politicians’ knees tells us little. Glass towers are indeed passive solar collectors, but at the worst possible time, mid summer. Robbed of the stuff of architecture they cannot mediate a comfortable environment.

Even more bizarrely, air conditioning entrepreneurs and their corporate clients want the same cool temperate climate for their people from the Equator to the Arctic so they can be confident that each employee stepping over the marble threshold of a chilled glass tower is immediately released from performance-sapping self-doubt. They believe unquestioningly that the cool temperate climate is the perfect environment for commerce, everywhere.

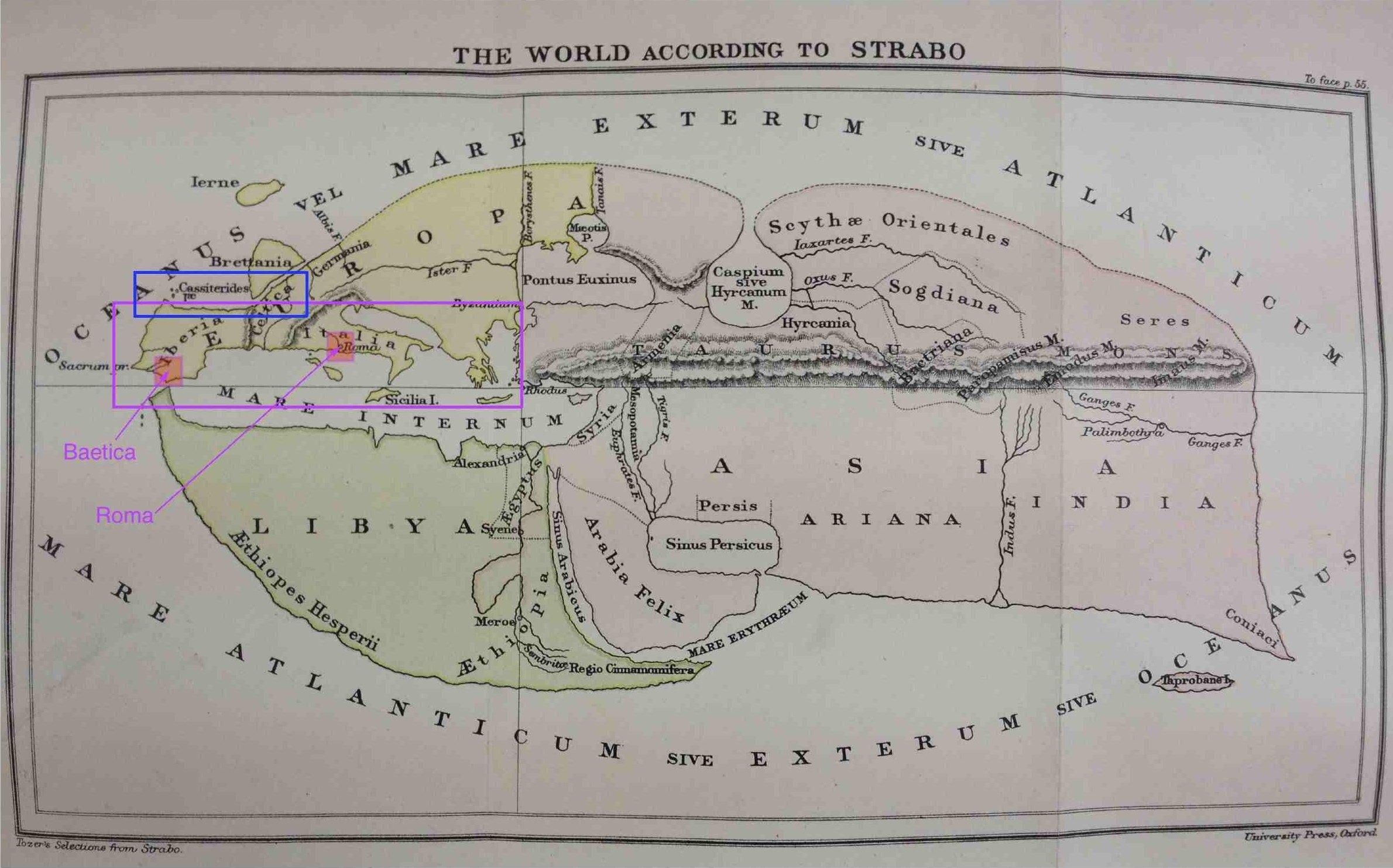

There is no cruder example of the environmental determinism that has infused at least the last two and a half millenia. It emerges in the writings of Parmenides, Strabo, Diodorus and Hippocrates of Kos, subsequently reprised for clients and their architects by Vitruvius. Hippocrates wrote disparagingly that the inhabitants of hot climates “are fleshy, ill-articulated, moist, lazy, and generally cowardly in character. Slackness and sleepiness can be observed in them, and as far as the arts are concerned they are thick-witted and neither subtle or sharp.”

Anthropogeographer Ellen Semple wrote in 1911: “Where man has remained in the Tropics, with few exceptions, he has suffered arrested development. His nursery has kept him a child. without the respite conferred by a bracing winter season.”

Eight years later the unestablished Yale academic Ellsworth Huntington was publishing maps of the “Distribution of World Civilisation” and “The Distribution of Human Energy” depicting whole continents as uncivilised and feckless simply because they were hot. The freezing air of the icy mountaintop was presented by Nietzsche as the ideal environment for the isolated chief executive officer, in Thus Spake Zarathustra: “The hour in which I frost and freeze, which asketh and asketh and asketh: ‘Who hath sufficient courage for it? Who is to be master of the world?’”

The Nietzschean “world conception” appears to have so informed the ethos of early business education that Santiago Iñiguez de Ozoño, the Dean of Spain’s IE Business School, could respond, in a debate about the transformation of the business education ethos globally one year after the 2008 banking crisis: “It is a different sort of leadership than the one which has grown in the past decade ... We will also see in the future many institutions getting rid of this spirit of elitism or arrogance which has contributed to create this atmosphere of overconfidence. They [believed that they] were actually beyond any controls or rules — that Nietzschean moral of the super-masters.”

Did the graduating classes under the original ethos literally recreate Nietzsche’s icy environment for themselves as the new “super-masters”? The Greek geographer Strabo described in great detail the perfect climate for a great civilisation, the warm temperate Mediterranean. Somehow this perception of the necessary climate for peak civilisation morphed into the Cool Temperate climate of northern England and north-west France.

Ferociously competitive air conditioning corporations bombarded the American public with marketing campaigns themed around “Emulation”, Thorstein Veblen’s depressing theory of an essentially greedy society. Advertisements depicted such things as shiny happy families gathered around their new air-conditioner being served by “failed” individuals beyond their glass enclosure, sweating gardeners labouring for them in the summer heat (advertising the Mueller Climatrol Type 910, 1955), or Mexicans slumped under sombreros sleeping through the working day (Carrier advertisement in the Saturday Evening Post, 1949). Businessmen in blue ties prospered in their manufactured temperate microclimates in icy penthouses while heavily perspiring contemporaries in yellow ties struggled in ambient temperatures with just the windows open many cheaper floors below.

There were many sceptics of these new refrigerated environments. After visiting Frank Lloyd Wright’s new Johnson building in Racine, Wisconsin, in 1940, Henry Miller wrote an account entitled The Air-Conditioned Nightmare: “This place is flawless — deathlike. Man has no chance to create once inside this mausoleum. Down with Frank Lloyd Wright!”

But from 1950 the Internal Revenue Service was persuaded to give tax deductions for homeowners who installed air-conditioning. Complicit doctors could prescribe air-conditioning as a medical necessity earning their patients tax credits. And all critics were suppressed.

In the not-so-distant past some of us at Cambridge were treated to a candid analysis of the energy demands of a new central London glass tower in a discussion about meeting Mayoral on-site renewable energy requirements and, more pertinently, how on earth to deal with a potential doubling of the requirement.

No technology stuck on to a business-as-usual glass tower will deliver this. We saw that plastering all the glass facades and roof with photovoltaic panels, which incidentally get very hot (Scheerbart would love the irony in that), would deliver only 2.7 per cent of the base energy requirement, and all the windmills you could cram on the roof, just 0.2 per cent, and an ever fashionable Combined Heat and Power machine, 2.3 per cent. Only drilling down boreholes could achieve 10 per cent but our Earth Scientists tell us that there are too many already under London.

What is needed is better designs responding to the actual climate and the adaptive capacity of the local population, more substantial less ephemeral buildings. All this energy is being poured into sustaining an outmoded aesthetic. It came out of a wildly complicated set of accidental collisions of poetic visions, new technologies and materials, rapacious entrepreneurs making new markets, suspect philosophical musings about the ingredients for success and old fashioned bigoted environmental determinism. It is time to acknowledge this and move on.

C. Alan Short is the Professor of Architecture at the University of Cambridge and Fellow of Clare Hall.

The Recovery of Natural Environments in Architecture by C Alan Short, Taylor and Francis has just been published.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments