Functioning human mini-kidney grown from stem cells in mice for first time

'This work greatly advances our progress towards using stem cells for kidney repair'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Functional human “mini-kidneys” capable of filtering blood to produce urine have been grown in a living organism in a medical first that marks a major step towards treatments for kidney disease.

Researchers have been able to develop human stem cells into a mini-kidney which is “markedly more mature than any previously reported findings”.

It is complete with functioning human blood vessels and able to filter the blood of its mouse host.

The team, from Manchester University, were able to produce their advance by doing the final stages of the kidney growth in a mouse subject, rather than a petri dish.

“Nobody has done this before,” the project’s lead, Professor Susan Kimber of the university’s Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health told The Independent.

“We’re the first to put these kidney cells into this in vivo [living] environment and show they can function.”

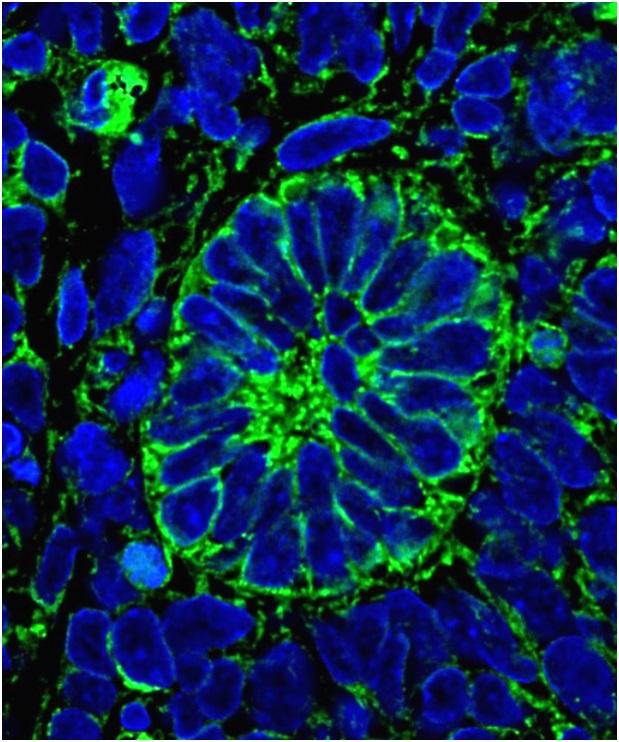

The team showed that fluorescent dye, injected into the mice, was being filtered from the blood and into the kidney tubules.

“The tubule’s job is to selectively reabsorb key molecules, mainly salts but also things like glucose, to stop them being wasted, and we saw that as well,” added Professor Kimber.

Recent efforts to create artificially grown kidneys has focused on growing complete organs in the lab, with the aim of transplanting them.

But Professor Kimber says no other group has managed to make their kidneys work.

The Manchester team are the first to grow working nephrons, the drooping branch-like structures of the kidney which filter blood at one end and release the collected waste at the other.

“It’s not equivalent to a kidney – we only had a few hundred nephrons and a human kidney has millions – but it has all the elements from blood flow in, up to the exit at the ureter – which takes the urine away.”

Co-author Professor Adrian Woolf, who is also consultant in Paediatric Nephrology at Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, said: “Worldwide, two million people are being treated with dialysis or transplantation for kidney failure and sadly another two million die each year, unable to access these treatments.

"So we are tremendously excited by this discovery – we feel it is a big research milestone which may one day help patients."

In the paper, published in the Stem Cell Reports journal, the team explained how human embryonic stem cells were first grown in a “nutrient broth”, to promote their initial growth into kidneys in laboratory dishes.

They were then implanted under the skin of the mice and matured over three months.

The findings "greatly advance" the effort to use stem cells for kidney repair, although it remains to be seen whether the new cells could “develop and survive in a hostile, damaged kidney environment”.

It could also be used to grow whole organs for transplantation, if the process can be refined and scaled up, Professor Kimber said.

The stem cell process avoids the risk of an organ being rejected by its host, as their own blood cells could be reprogrammed into stem cells and nurtured into a kidney before being implanted to develop.

However Professor Kimber warns it would be an “expensive process” to produce enough cells, and there are other problems to crack first.

The Manchester team’s next step is to try connecting their mini-kidney to a major blood vessel by implanting it near an artery, instead of under the skin.

This is essential because a high rate of blood flow is needed for the kidney to usefully filter and clean the blood of biological waste products that build up.

Metabolic waste build-up is what eventually poisons the body of patients with kidney disease, and the reason they require dialysis multiple times a week to perform the role of their kidneys.

They also need to connect it to the excretory system to allow urine to be passed out of the body.

Independent academics said there has been “hype” around lab-grown, 3D-printed organs, which has missed the bigger picture of getting them to function.

Prof Sheila MacNeil, Professor of Tissue Engineering at the University of Sheffield with “better plumbing” the advances here could lead to replacement organs.

“This study bridges the gap between getting stem cells to differentiate into cell types that we need in the lab and actually moving them towards making an organ," she said.

“This is a key step showing that the cells had the potential – what was needed was to give them an appropriate environment in which they could self organise.

“This study points the way to one day achieving growth of new kidneys to replaced damaged kidneys in patients.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments