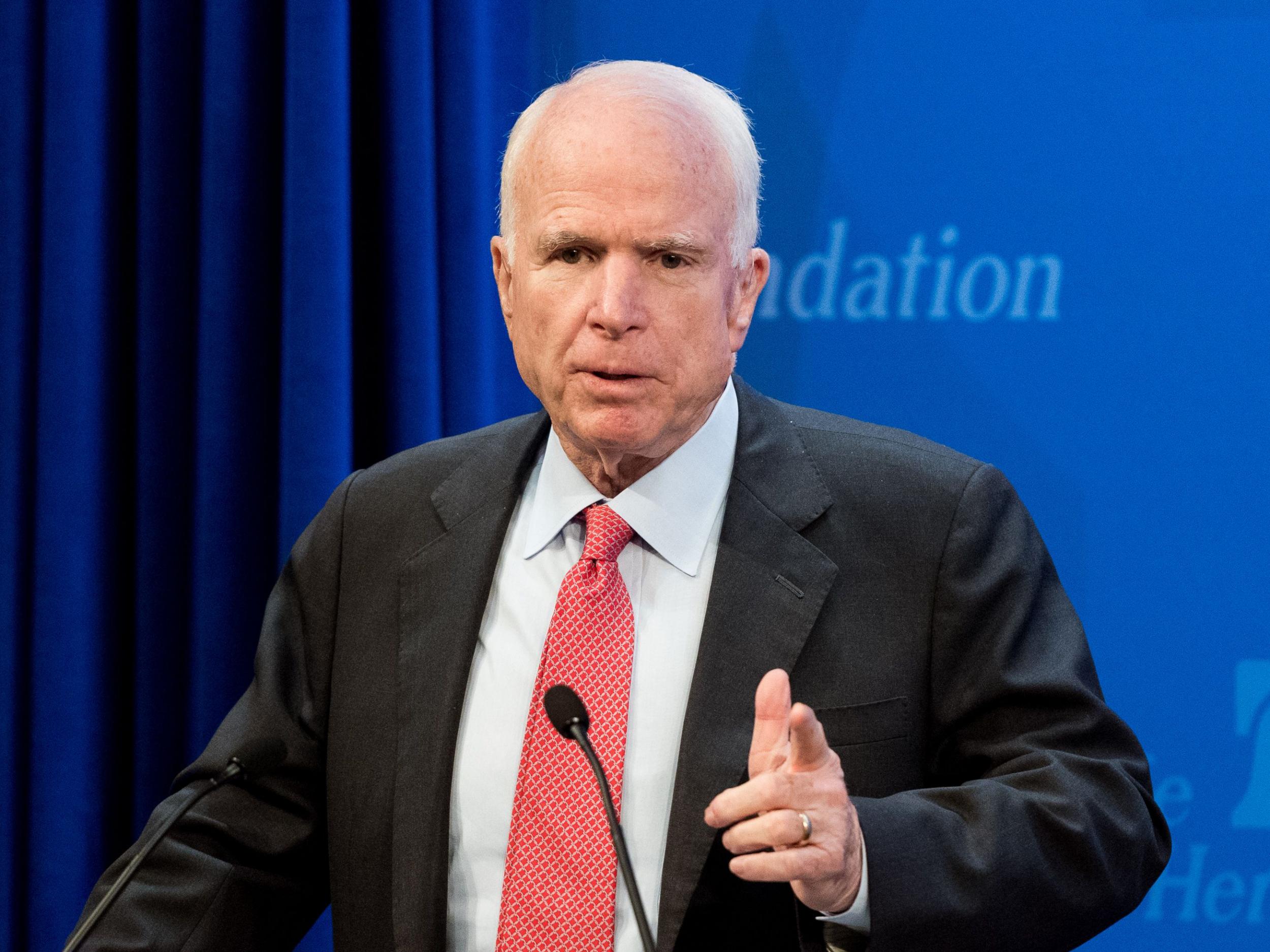

Glioblastoma: Understanding the brain cancer that John McCain has been diagnosed with

Survival rates remain low but brain cancer experts are 'very optimistic' about new treatments

John McCain has been diagnosed with a type of brain cancer called glioblastoma – an aggressive and particularly deadly form of the disease.

Glioblastoma is the most common type of cancerous brain tumour. Around 2,200 cases are diagnosed each year in England, while in the US, the figure is believed to be close to 12,400.

The 80-year-old senator, who stood against Barack Obama as a presidential candidate in 2008, had an operation last week to remove a blood clot from above his left eye, which was found to be a sign that the tumour had begun growing.

Mr McCain is a long-term survivor of melanoma. But doctors have classified this new cancer as a “primary tumor,” meaning it's not related to the skin cancer he had removed four times, first in 1993 and the others in the early 2000s.

Brain cancer expert Dr Paul Mulholland, who specialises in glioblastoma, told The Independent while a lack of understanding has led to limited options for those diagnosed with the disease, medics are “starting to understand more” about the condition and how best to treat it.

What is the difference between glioblastoma and other types of brain cancer?

More than half – around 55 per cent – of malignant brain tumours are glioblastoma, according to Public Health England. More men than women are diagnosed with the disease each year, with around 60 per cent of new cases occurring in men.

Glioblastoma is a primary brain cancer, which means it starts in the brain. It is distinctive to other, similar tumours as it is much more aggressive.

“Other types of primary brain cancers are lower-grade tumours. They tend to occur in people who are much younger, in their 20s and 30s, although they can get glioblastomas as well,” said Dr Mulholland.

Lower-grade brain tumours are “less aggressive, but they can be much larger as they grow so slowly. They can transform into glioblastoma.”

Sometimes glioblastoma can behave aggressively from diagnosis. This is more common in people over 40, he added.

How is glioblastoma treated?

The standard treatment for glioblastoma is radiotherapy and chemotherapy, although “drug treatments aren’t very effective for brain cancer,” said Dr Mulholland.

Depending on where the tumour is located in the brain, it may be possible to remove it through surgery – a common procedure for many people diagnosed with the disease.

“There are certain low-risk areas of the brain where you can operate safely, and then there are others where you absolutely cannot cut the tumour out, as it would be too devastating.”

Parts of the brain associated with movement and the senses, known as the “eloquent areas”, must be avoided, while the frontal and temporal areas of the brain, which deal with personality, are generally safer to operate on.

“We know the location of these areas, and we can use 3D imaging, so the surgeons can make a very accurate assessment of whether they can operate, and how much they can,” he said.

“There are also physical concerns – can they get in without going through other important tissue? If the tumour is on the outside location of the brain, and it reaches the surface of the brain, the surgeon can go in and cut it out from that surface.”

What are the survival rates?

For patients over 55, survival rates for glioblastoma are very low – about 4 per cent, according to the American Cancer Society.

Even among those who respond to drugs and radiotherapy, the cancer can come back, and often within 12 to 24 months.

What new treatments are being looked at?

Dr Mulholland said he is “very optimistic” about new treatments including new drugs and immunotherapy for treating glioblastoma in future.

Immunotherapy, a new type of medicine that boosts the body’s immune system to fight tumours, is currently being investigated through clinical trials.

“Some of the results are disappointing but we’re seeing that it could be transformative,” said Dr Mulholland, who has treated people with immunotherapy. “We’re getting long-term survivors. It’s only a fraction of the patients, but we’re starting to understand who they are.”

He and his colleagues are now setting up a national immunotherapy trial, and are in discussions with University College London (UCL) and the company who owns the drug, called ipilimumab, who has agreed to provide it for free for the duration of the trial.

“These drugs are very expensive, but the drug company has given it to us for free to do the trial in the UK, which will be a big benefit for the British patient.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies