The Big Question: Is Britain's international ranking in higher education likely to fall?

Why are we asking this now?

For the first time since Labour came to power university budgets are being cut. According to allocations this week from the Higher Education Funding Council (Hefce), the body that handles university funding in England for the Government, three-quarters of English universities are facing real-term cuts as a result of the squeeze on public finances. The total higher education budget of £7.3bn for the academic year beginning in the autumn of 2010 is being slashed by £573m. This week's allocations show some universities doing worse than others – among the biggest losers are the London Business School, which is losing 14 per cent (when inflation is taken into account), and Reading, which faces a 7.7 per cent cut in cash terms. But Worcester University is a big winner; it has been given the biggest increase, of 13 per cent in cash terms, because of rising student numbers.

Where will the cuts fall?

The Funding Council has tried to protect teaching and research. So, universities that do particularly well in research and received a four-star rating or more in the last Research Assessment Exercise are being protected. That means that the top five research institutions, Oxford, Cambridge, UCL, Imperial and Manchester are receiving the lion's share of the research funding (33 per cent). The cuts are falling on capital funding, on money allocated for old and historic buildings, on some postgraduate courses and on two-year foundation degrees. This means that universities will have to call a halt to the massive campus expansions that have gone up in the past 12 years. The University and College Union (UCU) says it will lead to a cut in student numbers and the sacking of lecturers.

Will it lead to cuts in students and lecturers?

There will be some. The Funding Council says there will be 6,000 fewer people gaining places at university this year meaning that 220,000 would-be students are likely to be disappointed. Cuts are likely to lead to some reductions in academic staff as vice chancellors take a hard look at their offerings – which courses are recruiting well, which not – and whether academics are pulling their weight in all areas of research.

This is already happening – in fact universities are continually examining their strategy and making decisions about which areas to cut and which to build up. At the moment King's College London is axing its engineering department, Reading is looking to cut 37 jobs from a number of subjects including computer science, electronics, cybernetics, biology and chemistry, and Sussex is hoping to make 107 job cuts and lose some courses, including environmental sciences.

Should we be worried?

Some people are very concerned. Sally Hunt, the UCU general secretary, says the Government is abandoning a generation who will find themselves on the dole, along with sacked teaching staff. The National Union of Students is warning of a "summer of chaos" as the cuts are combine with a clamour for places.

Professor Steve Smith, president of the umbrella group Universities UK, says the cuts cannot be considered good news, though he appreciates Hefce's efforts to protect core university funding. Like other critics, he is worried about the future. Les Ebdon, chairman of million+, the group that represents new universities, says: "For universities this is a phoney war because this funding settlement could be completely blown out of the water if there is a second Budget after the general election which makes further cuts to higher education. Many institutions, especially those with a focus on widening participation, could be reduced in size."

Will universities close?

It's possible, if an institution goes bust or suffers a catastrophic loss in public confidence, but this is thought to be unlikely. Closing a university would be very costly. It would be strongly opposed by local MPs and others with an attachment to it, including its students and academics. If a university were to go under, the most likely course is a merger of the kind that has happened in the past. The global credit rating agency Moody's stated this week that British universities were strong enough to survive the cuts. "The UK higher education section is likely to remain resilient in the face of change and to keep its strength over the long term," it said.

Are other countries doing the same?

Some other indebted nations are having to take the axe to universities. These include nations hardest hit by the recession, usually with governments that have large deficits and with economies built on the housing bubble and consumer debt. They are Ireland, Portugal and Spain, and some states of the USA. Fees have been hiked to more than $10,000 a year in California leading to widespread protest. But other governments, such as France and Germany, have preferred not to cut universities on the argument that higher education is the key to short-term economic recovery, long-term competitiveness and their own political viability. Under Obama, the US federal government poured money into higher education as part of a stimulus package but it was not enough to avoid staff lay-offs or a reduction in access.

How will Britain's global standing be affected?

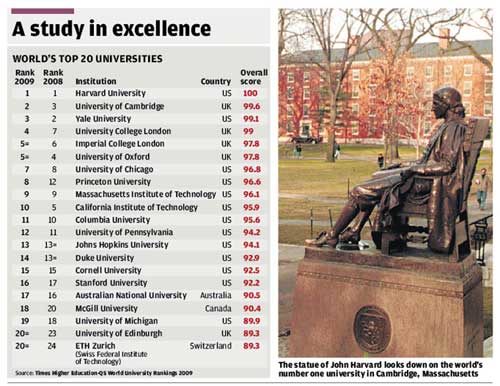

It might decline over the long-term, which is a real worry, especially for the Russell Group of research-intensive universities. In a statement this week, Wendy Piatt, director general of the Russell Group, pointed out that our competitors in Europe, Asia and the USA are pouring more money into higher education as a strategy for coming out of the recession. Without further investment the quality of the student experience and the reputation of English higher education will suffer, according to a report produced by JM Consulting for Hefce. This report showed that universities need an extra 15-20 per cent funding for current teaching to be sustained.

What is happening in India and China?

Both nations are investing heavily in higher education. In China enrolment in universities has mushroomed from 6 per cent in 1999 to 20 per cent in 2005 and there is a big concentration on science and engineering. China plans to become a world leader in science and technology by 2050. If current growth rates continue, China could overtake America in the number of researchers by 2021. This week the Indian government announced a plan to allow foreign universities to set up campuses and offer degrees as part of a reform of Indian higher education. This is likely to lead eventually to many more Indians staying at home rather than seeking a higher education in Britain or America.

Does our relative position in the world matter?

Yes: we cannot afford to be complacent. With countries like India and China emphasising university education as an economic generator and putting money into developing high-quality institutions, English universities have plenty of competition. If the best were to suffer years of being squeezed, particularly in research, it would affect our standing internationally.

Are universities right to make a fuss about the funding cuts?

Yes...

* If the reductions were to continue, there would be serious cause for concern

* For the sake of the economy, cutting higher education is not a good idea

* We will be limiting opportunities for the next generation, who deserve much better

No...

* Overall the cuts are pretty minor and universities can live with them; they're well paid already

* Higher education has to take its share of the pain when the nation is so indebted

* Universities could do with a bit of a shake-up and learn to be more efficient

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies