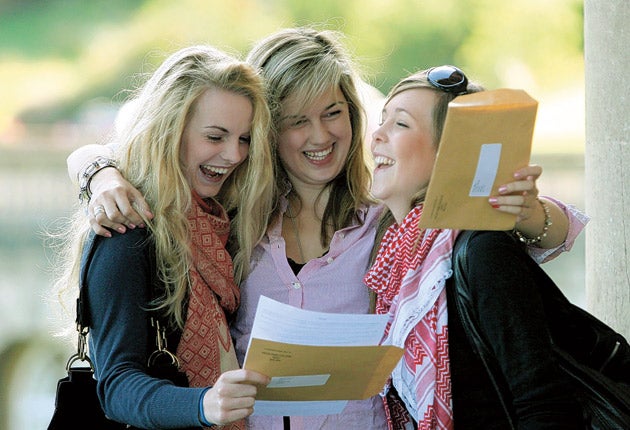

Star students: New A* grades have revived debate about dumbing down

A-levels need further reform still, says Richard Garner, but exam quality is only part of the problem

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.They call August the silly season because of the lack of news around, what with everyone going on holiday. As a result, newspapers are said to rely on ever sillier stories that would not see the light of day in more newsworthy times. Sometimes, to a seasoned education journalist like myself, it seems that this silliness even extends to the only real news story that can be guaranteed to emerge in August: exam results.

For years now, as A-level results have improved year on year for the past 24 years, we have obsessed about whether the exam is now easier than it was in the days when those spouting forth their opinions took it. We should make it harder, they say, presumably dramatically reducing the pass rate and allowing more youngsters to have spent two fruitless years in the sixth form and ending up with no qualification after it and being virtually unemployable. (The latter is not their argument. That's my interpretation of what would happen.)

The truth, though, according to studies over the years from organisations such as the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (in the days when it was the exams watchdog) is that A-levels are now different. Not necessarily easier or more difficult, but different.

Syllabuses have quite rightly changed over the years, making it difficult to make comparisons. After all, when it was first launched, discoveries such as DNA had not yet been made, so surely the content should change to reflect that and include questions on it.

Priorities have also changed since it was introduced in the 1950s when only a handful of youngsters from each age cohort went on to university – around 6 per cent, as opposed to the mid-forties today. Then it was unashamedly an elitist exam which, to exaggerate a point, decided which public schoolboys (and I mean boys) would go on to university.

Nowadays, it is an exam taken by more than 40 per cent of youngsters. It has, as the Cambridge University admissions officer Geoff Parks told The Independent, had to be made accessible to a wider range of youngsters.

The nature of the questions has therefore changed. Over the years, they became more knowledge-based rather than allowing for the freedom of expression and argument which can aid university admissions tutors in selecting the brightest and most talented youngsters for the most popular courses – law and medicine.

Incidentally, Dr Parks indicated that a by-product of this change – which exam boards would never admit to – has been a kind of "dumbing down" of the markers. As more and more have had to be hired to cope with the massive increase in the amount of scripts to be marked, so subject teachers with less depth of subject knowledge than the few recruited to mark them in the old days have had to be hired.

The question is: should we be worried about this trend, and what should we be doing about this?

The answer is surely that we should not be worried about the growth in take-up of A-levels. The UK still lags well behind the average for the Western world in staying-on rates in education post-16, according to the latest figures available from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. In addition, despite growing support in some circles that we are simply admitting too many youngsters to university (try telling that to the 180,000 applicants who are likely to be refused a place this year!), we still lag behind the Westerm average in terms of the percentage going on to higher education.

Indeed, while the UK is busy cutting spending on higher education, many Western countries – notably the United States, France and Germany – have seen the current economic climate as a reason to invest more in higher education for the future.

That having been said, there is no doubt that the exam needs reform, because it no longer serves its purpose of giving university admissions staff the ammunition they need to select the most talented youngsters for courses.

There should be a return to more open-ended questions as part of the exam to let youngsters show their thinking skills more clearly.

A start has been made in this direction this year, with new questions designed to "stretch and challenge" pupils being included. In addition, the A* grade has been introduced for the first time – and will be available to all those candidates who score 90 per cent in their A2s (the modules taken in the second year of the A-level course).

Michael Gove, the Education Secretary, is promising a further review of A-levels to allow more "deep thought" to be shown by candidates in their scripts.

The trouble is, as Cambridge University – one of the first universities to insist on all applicants being predicted to get at least one A* grade – has found, the supply of students expected to clear this hurdle far outstrips the number of places it has on offer. It has still had to reject around 8,000 candidates this year – all of whom have been predicted to get at least one A* grade pass.

There is also a question-mark over whether the introduction of the A* grade will aid more independent school pupils to snap up places at elite universities. The theory goes that they will be more inclined to push their pupils to obtain the new grade and are expected to obtain around three times as many as state school pupils.

It may not matter so much this year as very few universities have decided to make expectation of an A* grade a condition of the offer of a place – preferring to see how the system beds down before they do so. However, if it is true that independent schools are more likely to push their candidates to obtaining A* grades (and remember it is the independent sector that says this), then surely state school teachers will have to get used to doing likewise.

Whatever the situation, though, university admissions tutors will still face difficult – almost impossible – decisions in deciding which of the plethora of candidates facing them with A* grades are the brightest and most talented.

The sensible way round this dilemma is to allow them access to the marks of potential students to see if they just scraped to an A grade (or even an A* grade) as opposed to passing the grade barriers with flying colours before deciding whether to admit.

It would be logical and – unlike the present system – would be easily explainable to a visitor from, say, Mars, stumbling on our university admissions system for the first time.

Trouble is, though, it would only work if we had a sensible admissions system. Instead, we have to rely on awarding places based on predicted grades because there is too little time to start the admissions process after results have been announced. (Predicted grades, incidentally, are often wrong, so that top universities tend to ignore schools' assessments of their students and rely on the only hard evidence they have access to: the results of AS-levels taken at the end of the first year of the sixth form.)

To move to the kind of sensible system we need would either require the universities to put back the start of their academic year or insist that candidates sit A-levels earlier.

Both notions have met with fierce resistance. The universities claim it would reduce the number of international students that they rely on for finance through full-cost fees. They would not be prepared to kick their heels for three months to wait for a place at a UK university, they argue. The schools say it would not give them enough time to cover the syllabus.

Of the two arguments, I consider that of the schools to be the weaker one. It has often been said that key stage three (for 11 to 14-year-olds) could be covered in less time and, indeed, some schools do concertina the three years of study into two to allow their students to start GCSE courses earlier. Surely this could then be carried through so they start A-level studies earlier?

On the question of the international students, though, I can see that UK universities need to be able to attract them in droves to retain their world-class status. Not to put too fine a point on it, either, they need the income they derive from them by being able to charge them full-cost fees.

Michael Gove is considered a radical when it comes to reforming the education system. David Willetts, as Higher Education minister, is considered one of the finest brains in the Cabinet. Dare I say it should not be beyond the wit and wisdom of the duo to set this particular hare running?

Many serious education thinkers (although perhaps not some of the bureaucrats whose special pleading against making the change should be ignored) would be overjoyed if we opted for this radical reform. It could go a long way towards ending all the bleating about how A-levels were no longer fit for purpose once and for all.

A-levels – an evolution

* A-levels were introduced as a public examination in 1951. At that time only about 6 per cent of the age cohort went to university, and the number of students sitting the exam reflected that figure.

* The numbers taking the exam grew – as did the percentage of youngsters going to university. Currently, just over 40 per cent now sit the exam.

* The exam remained in its original form with students traditionally taking three subjects until the turn of the century, when a major review was implemented. This brought in the concept of the AS-level, worth half an A-level, which was taken at the end of the first year of the sixth-form. It was an attempt to broaden the sixth-form curriculum, with most youngsters studying four subjects up to AS-level and then ditching their weakest one in the second year of the sixth-form.

* Now reform is in the air again with the introduction of the new A* grade for the first time this year. Questions have reverted to the more open-ended style adopted originally in an attempt to stretch the brightest youngsters and allow them to give evidence of their thinking skills.

* Michael Gove, the Education Secretary, is planning further reforms. He would like to see an end to AS-levels to allow youngsters in the sixth form to indulge in more "deep thought" rather face an endless succession of modules leading towards the qualification.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments