Co-op banks preside over the growing breed of state schools in England

Co-op banks may be beset by scandals, but the movement also presides over a fast-expanding group of schools. Richard Garner finds out how one of its secondaries puts the ‘values-driven, faith-neutral’ philosophy into practice

Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

Louise Thomas

Editor

“We all get on better if we work together,” says Katy Simmons, who chairs the governing body at Cressex Community School in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire. “We don’t want to be isolated – we don’t want to be competing with everybody in our area.”

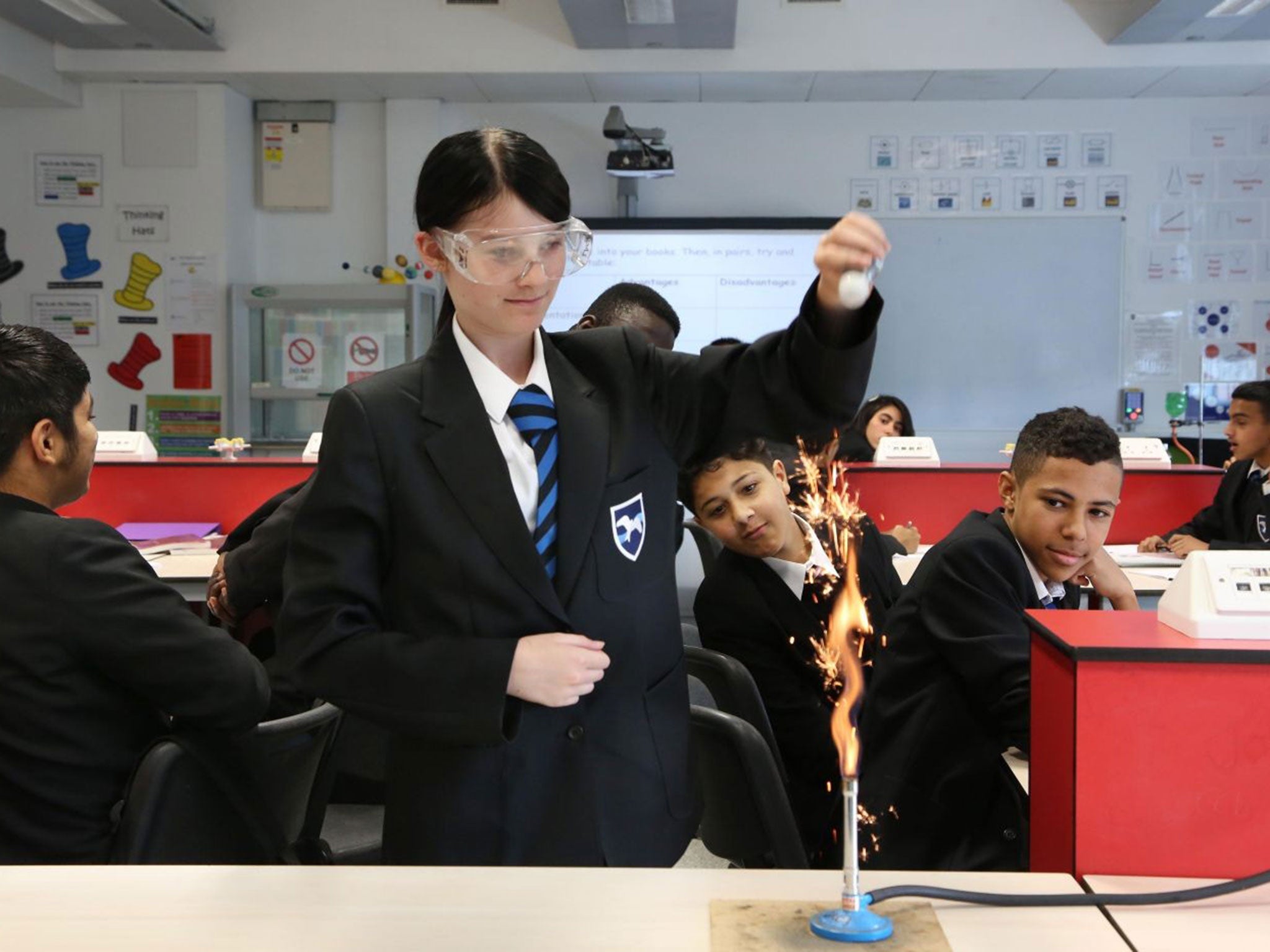

Cressex Community School is one of a growing breed of state schools in England that are putting the Co-op’s philosophy of equality and solidarity into practice by adopting the Co-op model to conduct its affairs.

With all the rhetoric about the Government’s reforms to the structure of education over the past decade (both from the pro and anti side), you would be forgiven for thinking we were in the grip of a wholesale privatisation of the school system. There are hedge-fund managers setting up academy schools, various faiths and persuasions opening up new free schools, academy chains whose roots stem from the independent sector acquiring more and more of a footing in the state sector – sometimes against the will of the people who work in, and provide the pupils for, them.

In the midst of all this, then, it might come as a surprise to know that the biggest accumulator of new schools in recent years has been the Co-op movement – which has a hand in running 800 state schools and is expanding all the time.

“It really has accelerated,” says David Hood, Cressex’s head teacher. “When I started here in 2008, I think the Co-op had about 100 schools. We were the first in Buckinghamshire.”

In fact, it has 767 schools at present – 718 foundation-trust schools, 44 academies and five business and enterprise colleges. The Labour Party conference last week heard calls to expand that number to as many as 3,000 by the end of the decade, as will this month’s Co-operative Party conference.

Cressex was a secondary modern school operating in one of the few counties to retain a fully selective secondary-school system. It was built in the 1960s and, by the turn of the century, was operating in buildings that Hood described as “not fit for purpose”. It had amalgamated with a neighbouring secondary modern school and therefore grown to twice its original size. “There was a perception that the behaviour wasn’t controlled and that students didn’t make the progress they should in their lessons,” Hood says. In September 2008, only 72 parents opted for a school with 150 places at its disposal.

Something had to be done and – under Labour’s national Challenge programme to improve standards in underperforming schools – Cressex was given three options: become a sponsored academy; join a federation of schools; or become a trust, which opened the door for the Co-op to come in. Under the former Education Secretary Michael Gove’s reforms in this current Government, it would not have had the choice – it would have been a prime target for compulsory academisation.

It was the Co-op’s motto of “values-driven, faith-neutral” that intrigued Hood and the governors. Also its ethos of “co-operative values of self-help, self-responsibility, democracy, equality, equity, solidarity” and “ethical values of openness, honesty, social responsibility and caring for others”.

“It’s not woolly words,” Hood insists. It means, for instance, that everyone at the school has a stake in its future. The head boy and head girl are on the school’s governing body and pupils have a say on staff appointments.

It has an elected schools council – which spends much of its time devising ways of raising money for charities. “Sometimes we react to what’s happened in the news,” 14-year-old Leah Butler says. Recently, they raised money for fighting cancer after reading of teenager Stephen Sutton’s heroic fundraising efforts as he battled against the disease.

The school has also struck up a fruitful partnership with a neighbouring private school, the exam-league-table-topping Wycombe Abbey School, which has helped students from different backgrounds to get to know each other.

Cressex’s intake is largely pupils of Pakistani heritage (about 70 per cent of the intake – with the rest divided between white British and a wide range of ethnic-minority groups). At the last count, its pupils spoke around 30 languages.

Despite Buckinghamshire’s reputation as one of the leafiest shires in the country, it has an above-average percentage of pupils entitled to free school meals – adding fuel to the controversy over whether the remaining grammar schools are creaming off the middle classes at the expense of less advantaged pupils.

From Cressex’s perspective, the links between the two schools have opened up summer schools run by Wycombe Abbey for its pupils – which can give a taster of what life in higher education could be like. There is also a reading literacy programme whereby sixth-formers from Wycombe Abbey help struggling readers with their literacy – 22 took part in the scheme this year.

It works both ways. The pupils from Cressex improve their reading skills while the girls from Wycombe Abbey gain a useful addition to their CVs as they complete their Ucas forms. Universities and employers all say they are looking for more rounded applicants nowadays – not just products of exam factories.

In addition, trainee teachers from Wycombe Abbey have visited Cressex – broadening their experience should they go for another job.

The girls from Wycombe Abbey also take part in a drama workshop at Cressex which ends with their putting on a performance for the pupils. During the day, as they discuss their work – in this case, a performance of Hamlet – any initial awkwardness between the two sets appears to evaporate.

“At midday, we all walked over to the dining room and had lunch,” one Wycombe Abbey girl says. “I thoroughly enjoyed the day and improved my drama techniques and my understanding of Hamlet; however, most of all I met some lovely and kind people.”

Other trust members include the University of Buckingham and Bucks New University – a privately funded and a new university respectively. Johnson & Johnson, the international pharmaceutical company which operates nearby, is not – but helps students with their career options. One exercise it became involved in was reminiscent of the television programme Dragons’ Den – during which students worked on presenting a teenage cure for diabetes.

Cressex has obtained support from its local Conservative MP, Steve Baker, for its decision to become a Co-operative school. He extolled the virtues of Co-operative schooling in a House of Commons debate last year. He said the school had shown “a defiant spirit of autonomy and independence” faced with a whisper of forced academisation because of its results. “There was fierce determination to remain a Co-operative because of the way the Co-operative structure allows all parties to be engaged across the community,” he added.

Gareth Thomas, the Labour MP and chairman of the Co-operative Party, is also backing the expansion of the Co-op’s involvement in schools. He plans to raise the issue at the Co-operative Party’s conference this month.

Cressex can certainly testify that the approach raises standards – its English GCSE results improved this year against a background of national decline, with 54 per cent of pupils getting A*- to C-grade passes. It has also been rated as “outstanding” by the education-standards watchdog for its maths (64 per cent – higher than the national average – with A* to C grades) and its sixth-form provision, where it runs tailor-made courses in childcare and development.

“Co-op schools are the quiet success story of British education,” Thomas says. “They demand high standards, have strong leadership, and involve parents and the local community directly in the running of their schools. Free schools and academies have their enthusiasts but few have the level of local support Co-op schools achieve. Parents and the community have clear opportunities to have their voice heard.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments