What are the new GCSEs and what do the changes mean?

This year's GCSE candidates were the first to sit 'tough' new exams under a reformed curriculum - here's what the new grading system means

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

This summer’s GCSE candidates are the first to sit new, more rigorous exams as part of a shakeup to secondary school teaching and qualifications.

Thousands of teenagers across England can expect to receive their results on Thursday – but English and maths scores will come in the form of a new numbered grading system, rather than the traditional A*-U grades.

The dramatic reforms come as part of a government drive to improve schools’, pupils’ and employers’ confidence in the qualifications, ensuring that young people have the knowledge and skills needed to go on to work and further study.

But the new system has caused widespread confusion among teachers, parents and employers, with teaching unions claiming the majority remain unclear on what these new grades mean in practice.

Last week it was revealed that more than half a million pounds of public money is to be spent on explaining these changes and publicise the reforms, a move exams regulator Ofqual said was “essential”, since the changes will eventually be brought in for all subjects.

But what do the changes mean, in a nutshell?

According to Department for Education officials, the new GCSEs are “more challenging”, covering more content than in previous years.

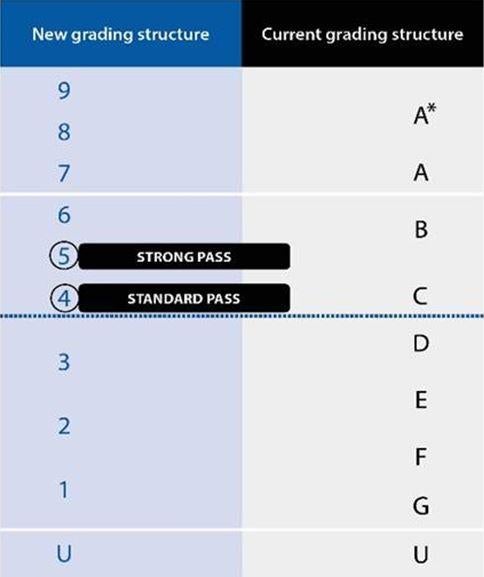

They are to be graded from 9 to 1, with 9 being the highest grade, rather than A*-G. New GCSEs are linear in structure rather than modular, with all exams at the end of a two-year course.

Why are they changing?

The new qualifications are the result of a long process of reform that began in 2011 with the national curriculum review in England, involving extensive consultation with schools, FE, HE and employers on the principles of reform and subject content.

“The GCSE grading scale in England is changing and we have revised our GCSE qualifications to make them more demanding,” DfE guidance states. “We have done this to pupils leave school better prepared for work or further study.”

The government says it wants to match school standard to those of the strongest performing education systems in the world – such as Hong Kong and Shanghai.

The new 9 to 1 grading scale aims to better differentiate between the highest performing pupils and distinguish clearly between the new and old exams.

When and where is this happening?

The first exams for the reformed GCSEs in English language, English literature and maths were held in summer 2017, with results due in August 2017.

Teaching of these new subjects started in September 2015.

The first exams for most other new GCSE subjects will take place in 2018 and 2019 (with courses taught from September 2016 or September 2017).

All GCSE subjects will be revised by 2018 and examined by 2020. Between 2017 and 2019, GCSE exam certificates will have a combination of number and letter grades. By 2020, exam certificates will contain only number grades.

These changes are only happening to GCSEs regulated in England, however. Wales and Northern Ireland are also making changes to their GCSEs but are not introducing the 9 to 1 grading scale.

How do they work?

A new 9 to 1 grading scale will be used for the new GCSEs to show clearly whether a pupil has taken an old or a new GCSE.

The new grading scale has more grades at the higher end to recognise the very highest achievers. Grade 9 is the highest grade and will be awarded to fewer pupils than the current A*.

The Department for Education recognises grade 4 as a ‘standard pass’; this is the minimum level that pupils need to reach in English and maths (previously a ‘C’).

If pupils fail to achieve a grade 4 or higher, they will need to continue to study these subjects as part of their post-16 education. There is no re-take requirement for other subjects.

Will this mean a child gets a lower grade than the previous system?

Although the exams will cover more challenging content, the DfE insists this won’t necessarily mean pupils score lower grades than they might have under the old system. Exam boards will use statistics to set standards so that:

• broadly the same proportion of students will achieve grade 7 and above as achieved grade A and above in 2016;

• broadly the same proportion of students will achieve grade 4 and above as achieved grade C and above in 2016; and

• the bottom of grade 1 will align with the bottom of grade G in 2016.

But this assumes a stable entry to the exams. Where the entry changes significantly then the overall results in August will reflect any changes in the cohort of students.

For example we know that there has a large increase in numbers entering English Literature this year, and we expect that the average ability of the cohort entering the exams will therefore be lower than last year. If that assumption is correct, results will also be lower.

Experts have been critical of the reforms, with the Department's own chief analyst predicting that only two pupils in England are likely to achieve top grades in all the new subjects being phased in this year.

“2 is my guess – not a formal DfE prediction," tweeted Dr Tim Leunig, who is also chief scientific adviser to the DfE. "With a big enough sample, I think someone will get lucky...”

How do the two grading scales compare?

The old and new GCSE grading scales do not directly compare but there are three points where they align:

• The bottom of grade 7 is aligned with the bottom of grade A;

• The bottom of grade 4 is aligned with the bottom of grade C; and

• The bottom of grade 1 is aligned with the bottom of grade G.

In theory, a pupil who would have achieved a C or above in last year’s exams would gain the equivalent of a 4 or above if taking the exams this year.

Only the very top students will achieve a grade 9 - set at an even higher level than the previous A* grades.

How will schools be measured under this system?

Figures will be published detailing the proportion of pupils achieving both grade 4 and above and grade 5 and above.

Grade 5 and above is recognised as a ‘strong pass’ – this will be one of the headline measures of school performance.

Progress 8 – a scheme devised to judge schools across all grades and subject areas - will remain the government's primary accountability measure.

How will it affect applications for further education or jobs?

“Employers, universities and colleges will continue to set the GCSE grades they require for employment or further study,” states DfE guidance.

“We are saying to them that if a grade C is their current minimum requirement, then the nearest equivalent is grade 4. A* to G grades will remain valid for future employment or study.”

School Standards Minister Nick Gibb said of the changes: “This is the culmination of a six year process of curriculum and qualifications reform, which has involved wide consultation with teachers, schools and universities.

"The new GCSEs are more rigorous so that young people can gain the knowledge and understanding they need to succeed in the future and compete in an increasingly global workplace."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments