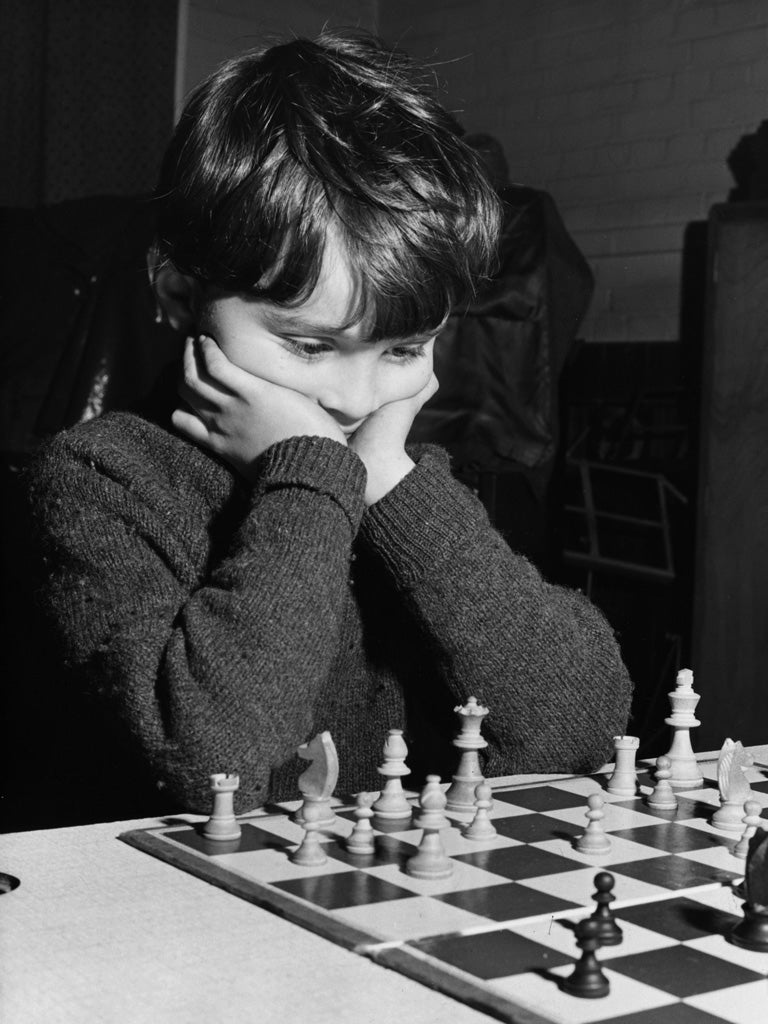

The great chess revival: how the ancient game sharpens young minds

After all but vanishing from schools, the game is undergoing a revival thanks to its problem-solving skills

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Legend has it that the 1,500-year-old game of chess was invented after India’s then-ruler asked his wise men to devise a way of teaching royal children to become better thinkers and better generals on the battlefield.

Now, 30 years after it all but disappeared from state education, chess is making a dramatic comeback in British primary schools. Teachers have come to see it as a major stimulant for improving pupils’ concentration, if not their war-winning abilities – with academics believing it can also be used to improve maths skills.

A total of 175 schools – including those serving deprived areas – have reintroduced the game to the curriculum in the past two years. The charity behind its revival, Chess in Schools and Communities (CSC), is optimistic that the take-up will spread to 1,000 state schools in three years.

As 10-year-old Olivia Kenwright took a break from playing the game during a timetabled lesson, she agreed she was pretty sure it was helping her brain. “It’s really good for helping out with other subjects,” she said.

Olivia is a pupil at Sacred Heart Catholic Primary School in Kensington, in the heart of inner-city Liverpool – one of the 175 schools to start playing the game again. Davidson John, another 10-year-old who was a keen footballer but now prefers the board game, agreed with her, saying, “It can help you with sorting out problems.”

According to Callum Phillips, 11, it is a “calm game”. “I play it with dad and grandad at home now.” That, according to Malcolm Pein, the chief executive of CSC, is a breakthrough because today’s children hardly ever play board games with their parents. “It’s just computer and video games,” he said.

“Chess fell out of favour very rapidly in state schools when teachers fell out with the Government in the 1980s and cut back on out-of-hours activities.”

“If you go to a state school in the UK there’s a less than one in 10 chance that they’ll do chess,” added Mr Pein. “Yet it is so easy to organise and costs so little in comparison with other activities.”

John Gorman, the chess coach for Liverpool schools, said: “It helps with developing children’s concentration skills and they’re doing calculations while they’re playing – like whether a rook is more important than a pawn and how important is a queen. ”

At Sacred Heart all children have either an hour or 45 minutes of timetabled chess a week, except for those in their first year of compulsory schooling. There is also a chess club.

The school won a Liverpool-wide schools’ chess competition, something which the headteacher Charles Daniels is very proud of. “We’re only a small, one-form entry school. We don’t win football and cricket competitions,” he said. Next month, a contingent from the school will travel down to Olympia in west London to watch the World Chess Championships.

Meanwhile, Mr Pein is busy exorcising the myth that chess is a middle-class game. He has encouraged several pupil referral units [PRUs] and one young offenders’ institution to take it up. “It has been popular in the PRUs,” he said, possibly as a result of its calming influence on players – it is widely encouraged in prisons in the US.

However, Mr Pein is battling against a culture which believes it does not need financial aid, a decision that dates back to just before the Second World War, when the Government produced a list of sports to be supported that would provide fit young people to help fight a war. It seems it neglected the need for fit young minds.

The picture is very different in other countries; in Armenia, which has an impressive record in producing world champion teams, it is a compulsory part of the curriculum. France, too, pours state aid into the game in schools. Some authorities do recognise the need to promote it. Bristol, for instance, offers chess in its primary schools and Newham in east London has asked CSC to produce a plan to introduce it in all its schools.

It is easy to see why heads are keen. A report by the chess master Jerry Meyers says: “We believe it directly contributes to academic performance. Chess makes children smarter.” An experiment in the US showed that after only 20 days of instruction students’ academic performance had improved dramatically, with 55 per cent of pupils showing significant improvement.

From Mr Daniels’ point of view, it has to compete with the pressures of the national curriculum – which have led to many schools believing they do not have time for such activities. From his perspective, though, the thrill his pupils got from winning a competition made it worth the effort.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments