Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

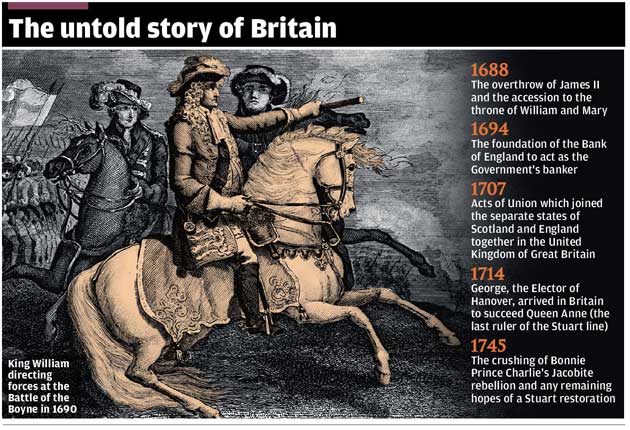

Michael Gove, the Conservative education spokesman, claims to have identified a "dark age" in the teaching of history in our schools. He believes that the era between the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the second Jacobite rising of 1745 is a crucial one in our national story, yet too often goes untaught.

So what precisely was the Glorious Revolution?

The 17th century in the British Isles can be loosely characterised as a long and bloody struggle between the monarchy on one side and the aristocracy and parliament on the other. It stretched through Charles I's civil wars and Oliver Cromwell's interregnum. The Glorious Revolution was the moment when the aristocracy and parliament came out, decisively, on top. In 1688 much of the political class detested the new king, James II, for his autocratic ambitions and – worse – his Catholicism. A powerful group of English aristocrats, nicknamed the Whigs, promised James's Protestant daughter Mary, and her husband William of Orange, ruler of the Netherlands, their allegiance if they would invade Britain and depose James.

James II fled without a fight and William and Mary became joint monarchs. But William and Mary owed the elevation to their Whig sponsors. The balance of power had shifted forever. From 1688, the monarchy would never overreach itself again, in the manner that James II or his father, Charles I, had.

And who were the Jacobites?

The supporters of James II did not disappear when the king went into exile in France. And many Scots were aggrieved at the treatment of their king and countryman. It is these people who became known as the Jacobites. The period 1688 to 1745 was a time of simmering dissent from these Jacobites and it periodically burst into open revolt. William inflicted a heavy defeat on the gathered forces of James II in Ireland, at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690.

When Queen Anne died in 1714 and was succeed by her cousin, George, the Elector of Hanover, the Jacobites rose up again. Once again they were put down. Thirty years later there came another, final, challenge to the new Hanoverian dynasty, led by James II's grandson, Charles Stuart, "Bonnie Prince Charlie", which was brutally crushed in the Battle of Culloden by the Duke of Cumberland. With that massacre the Jacobite movement was decisively broken.

So why was this era important?

Britain's great historical achievement has been its constitutional monarchy and its gift to the world has, arguably, been sovereign parliaments. Both of those innovations date from this period. People often complain that we lack a written constitution. They should look to the 1689 Bill of Rights which guaranteed regular parliaments, free expression and protection from military rule. This was the era in which two-party politics – between the Whig and Tory factions – began. It was also a time when Sir Robert Walpole fashioned the powerful position of "prime minister".

Did the changes extend beyond parliament?

The era witnessed the forging of the modern British state. The two parliaments of England and Scotland were formally unified in the Acts of Union of 1707. A sense of British national identity was strengthened in the battles against the French in the War of the Spanish Succession. The victories of the Duke of Malborough at Blenheim (1704) and Malplaquet (1709) date from this period. Britain also entrenched its identity as an anti-Catholic power. A long period of repression of internal Catholicism was formalised in the 1701 Act of Settlement, which prevented Catholics from inheriting the throne, or holding other high offices. This discrimination did not end until Catholic "emancipation" more than a century later. This was also a significant period in development of London as a financial centre. The Bank of England was established in 1694 by Royal Charter to lend to the government. Later it came to manage the national debt and lend to other commercial banks. It might also be useful to compare our present financial meltdown with the South Sea bubble, which burst with disastrous consequences in 1720. There were literary and artistic advances too. Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope flourished under Queen Anne. And the brilliant baroque composer Handel came to Britain as part of the court of George I.

So history students do not cover this period?

It is a long-standing complaint of university history departments that students emerge from school having studied the Tudor and Stuart era and the rise of the Nazis extensively, but with shockingly little knowledge of other periods of history. The A-level and GCSE syllabuses certainly give pupils ample opportunity to study these two areas. The Qualifications and Curriculum Authority identified a "gradual narrowing and "Hitlerisation of post-14 history," in its 2005 annual report.

So does Michael Gove have a point?

There is certainly a case for giving students as much chance to study the 1688-1745 period as they get to study Henry VIII and the Nazis. And there is also a strong case for transmitting to students a much broader sweep of Britain's history than they presently leave school with. A chronology would give students an over-arching knowledge of the history of their country, rather than the unconnected snapshots they tend to get at present. Mr Gove's ambition goes deeper, however. He told the Today programme yesterday that he wants students to be given a "narrative" view of Britain's history, in the manner of those eminent Whig historians Thomas Macaulay and George Macaulay Trevelyan.

What is the problem with this?

The classic Whig view – that British history followed a progressive trend towards, as Macaulay put it, an "auspicious union of order and freedom" – was challenged by a generation of revisionist historians in the wake of the First World War. These revisionists argued that this was a misleading prism through which to analyse the past. If you think history has an enlightened end-point you will tend to consider all events as flowing ineluctably towards it. It is dangerously deterministic approach. The argument of revisionists is that we should challenge the presumptions of the past, not acquiesce in them.

Are there any other problems?

The second objection is political. Mr Gove wants to give children a "narrative" of what Britain is and where it came from. But such a narrative is always going to open to challenge.

For instance, historians disagree on the legacy of the British Empire. Some regard it as a programme of relentless colonial expropriation. Others see it is as a magnificent global transmission mechanism for democracy and the rule of law, or a mixture of all of these hypotheses. Those politicians who believe Britons ought to be proud of their history will, naturally, favour the first narrative. But should politicians be in a position to decide matters of interpretation? Probably not.

Then there is the question of focus. Britain has always been affected by the sweep of continental and global politics. An exclusive focus on our "island story" could result in knowledge gaps among our students just as unfortunate as those that Mr Gove has highlighted.

Should we resurrect the 'Whig' school of history?

Yes...

* Children should be educated in Britain's gift to the world: parliamentary sovereignty

* Without being given a chronology children cannot hope to grasp our nation's story

* The present curriculum gives disproportionate emphasis to the Tudor period

No...

* The assumptions of the "Whig" school have been discredited

* It is equally important that children learn about European and world history, not just our "island story"

* History teaching needs to steer clear of political propaganda

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments