I can’t answer school exam questions about my own poems, says US poet

'How in the name of all that’s mouldy did this poem wind up on a proficiency test?'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Badly worded or poorly conceived questions on standardised tests are not uncommon (remember the question about a “talking pineapple” on a New York test in 2012?). But here’s something new: The author of source material on two Texas standardised tests says she can’t actually answer the questions about her own work because they are so poorly conceived. She also says she can’t understand why at least one of her poems - which she calls her “most neurotic” - was included on a standardised test for students.

The author is Sara Holbrook, who has written numerous books of poetry for children, teens and adults, as well as professional books for teachers. She also visits schools and speaks at educator conferences worldwide, with her partner Michael Salinger, providing teacher and classroom workshops on writing and oral presentation skills. Her first novel, “The Enemy: Detroit 1954” will be released March 7.

In this amusing but sobering post, Holbrook writes about the episode. This first appeared on the Huffington Post, and Holbrook gave me permission to republish.

The tests on which Holbrook’s poems appeared are the STAAR, the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness. The questions were released by the Texas Education Agency. Teachers use past test questions to prepare students for future exams.

By Sara Holbrook

When I realised I couldn’t answer the questions posed about two of my own poems on the Texas state assessment tests (STAAR Test), I had a flash of panic – oh, no! Not smart enough. Such a dunce. My eyes glazed over. I checked to see if anyone was looking. The questions began to swim on the page. Waves of insecurity. My brain in full spin.

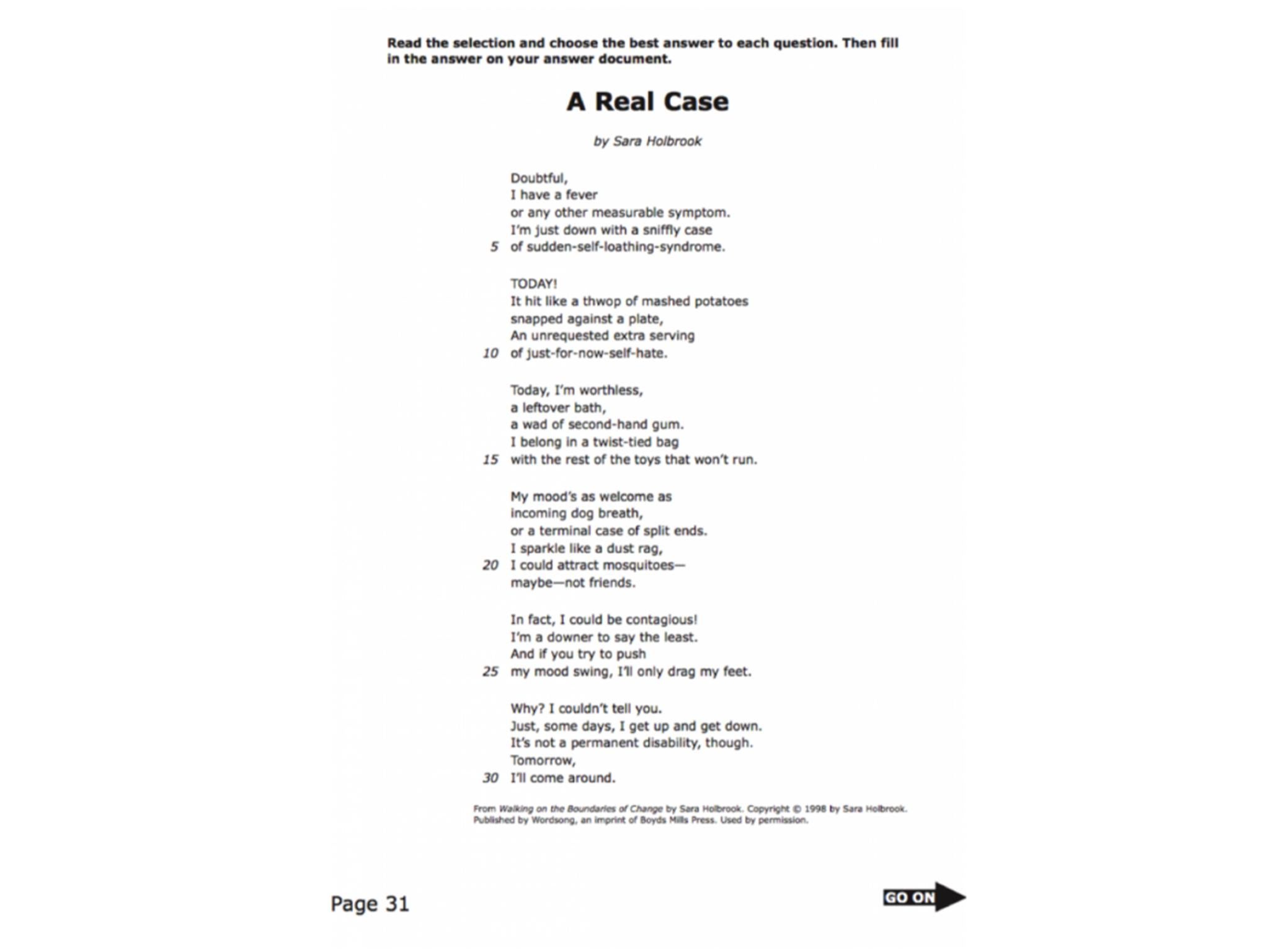

The two poems in question are “A Real Case,” appearing on the 2014 Grade 7 STAAR Reading Test, and “Midnight,” appearing on the 2013 Grade 8 STAAR Reading Test. Both poems originally appeared in “Walking on the Boundaries of Change,” Boyds Mills Press, 1998.

Let me begin by confessing that “A Real Case” is my most neurotic poem. I have a pile of them to be sure, but this one is the sour cherry on top. The written evidence of my anxieties, those evil gremlins that ride around on tricycles in my mind shooting my self-confidence with water pistols. How in the name of all that’s mouldy did this poem wind up on a proficiency test?

Dose of reality: test makers are for-profit organisations. My poems are a whole lot cheaper than Mary Oliver’s or Jane Kenyon’s, so there’s that. But how would your vulnerable, nervous, number two pencil-gripping seventh grade self have felt opening your test packet to analyse poetic lines such as this:

I’m just down with a sniffly case/of sudden-self-loathing-syndrome… an unexpected extra serving/ of just-for-now-self-hate.

Seriously? Hundreds of my poems in print and they choose THAT one? Self-loathing and self-hate? Kids need an extra serving of those emotions on testing day?

I apologise to those kids. I apologise to their teachers. Boy howdy, I apologise to the entire state of Texas. I know the ‘90s were supposed to be some kind of golden age, but I had my bad days and, clearly, these words are the pan drippings of one of them. Did I have a purpose for writing it?

Does survival count?

Teachers are also trying to survive as they are tasked with teaching kids how to take these tests, which they do by digging through past tests, posted online. Forget joy of language and the fun of discovery in poetry, this is line-by-line dissection, painful and delivered without anaesthetic. One teacher wrote to me last month, working after 10 p.m., trying to figure out the test maker’s interpretation of my poem “Midnight.” This poem isn’t quite as jarring as “A Real Case,” simply symptomatic of aforementioned neuroses: It’s about insomnia.

“Hello Mrs. Holbrook. My name is Sean, and I’m an 8th grade English teacher in Texas. I’m attempting to decipher the number of stanzas in your poem, ‘Midnight’. This isn’t clear from the formatting in our most recent benchmark. The assessment asks the following question:

“Dividing the poem into two stanzas allows the poet to―

A) compare the speaker’s schedule with the train’s schedule.

B ) ask questions to keep the reader guessing about what will happen

C) contrast the speaker’s feelings about weekends and Mondays

D) incorporate reminders for the reader about where the action takes place.

The answer is C) to contrast the speaker’s feelings about weekends and Mondays.

How many stanzas are in this poem? Where are they located? I would appreciate your help. Thank you so much!”

Oh, goody. I’m a benchmark. Only guess what? The test prep materials neglected to insert the stanza break. I texted him an image of how the poem appeared in the original publication. Problem one solved. But guess what else? I just put that stanza break in there because when I read it aloud (I’m a performance poet), I pause there. Note: that is not an option among the answers because no one ever asked me why I did it.

These test questions were just made up, and tragically, incomprehensibly, kids’ futures and the evaluations of their teachers will be based on their ability to guess the so-called correct answer to made up questions.

Then I went online and searched Holbrook/MIDNIGHT/Texas and the results were terrifying. Dozens of districts, all dissecting this poem based on poorly formatted test prep materials.

Texas, please know, this was not the author’s purpose in writing this poem.

At the end of this article is a question-by-question breakdown of the test questions on A REAL CASE and my thinking as I attempted to answer them. But fair warning: Your eyes are going to glaze over as you read through them. But try to hang in there. Pretend your future depends on it. That you might not be promoted into the next grade with all the other kids your height and will have to remain in seventh for the rest of your life if you don’t pass. Seventh grade! That muddy trough where kids try to keep afloat clinging to the wispy thread of: This won’t last forever. But if you don’t pass this blamed (blaming) test, it just might. Oh no! Put a pencil between your teeth, bite down, and open your test packet.

Meantime, here is my question:

Does this guessing game mostly evidence:

A the literacy mastery of the student?

B the competency of the student’s teacher?

C the absurdity of the questions?

D the fact that the poet, although she has never put her head in an oven, definitely has issues.

Let’s go with D since I definitely have issues, including issues with these ridiculous test questions.

The same year that “Midnight” appeared on the STAAR test (2013), Texas paid Pearson some $500 million to administer the tests, reportedly without proper training to monitor the contract. Test scorers, who are routinely hired from ads on (where else?), Craiglist, also receive scant training, as reported by this seasoned test scorer. I’m not sure what the qualifications are for the people who make up the questions, but the ability to ride unicorns comes to mind.

Now comes research that reveals that a simple demographic study of the wealth of the parents could have accurately predicted the outcomes, no desks or test packets needed. Educator and author Peter Greene reports,

“Put another way, Tienken et. al. have demonstrated that we do not need to actually give the Common Core-linked Big Standardised Test in order to generate the “student achievement” data, because we can generate the same data by looking at demographic information all by itself.

Tienken and his team used just three pieces of demographic data—

1. percentage of families in the community with income over $200K

2. percentage of people in the community in poverty

3. percentage of people in community with bachelor’s degrees

Using that data alone, Tienken was able to predict school district test results accurately in most cases.”

Now, technically Texas does not adhere to the Common Core, but since their tests are written and administered by the same sadistic behemoth, Pearson, it’s fair to draw some parallels. At least as fair as (say) those made-up questions about my neurotic poems.

When I heard the campaign promises to eliminate the Common Core made by Donald Trump, I thought, yeah, right. Wait until someone educates him on how much money is being made making kids miserable with these useless tests. Talk is cheap. School testing is big bucks, and those testers are not going down without a fight.

Stop it. Just stop it.

The only way to stop this nonsense is for parents to stand up and say, no more. No more will I let my kid be judged by random questions scored by slackers from Craigslist while I pay increased taxes for results that could just as easily have been predicted by an algorithm. That’s not education, that’s idiotic.

I won’t drag you through the entire dissection of my poem MIDNIGHT, just the concluding stanza:

...And I meander to its rhythm,

flopping like a fish.

Why can’t I get to sleep?

Why can’t I get to sleep?

14 The poet uses a simile in lines 23 and 24 to reveal that the speaker —

F wants to be outside G cannot get comfortable H does not like fishing J might be having a dream

I say G, H, and J. I can’t get comfortable with any of this, it all seems like a bad dream (which indeed can keep me awake) and correct, I don’t like fishing (ick, worms). But fishing through school testing is even creepier than a fistful of worms, especially when it’s mislabeled as a legitimate measure of student and teacher competency.

Parents, educators, legislators, readers of news reports: STOP TAKING THESE TEST RESULTS SERIOUSLY

Idiotic, hair-splitting questions pertaining to nothing, insufficient training, profit-driven motives on the part of the testing companies, and test results that simply reveal the income and education level of the parents – For this we need to pay hundreds of millions of dollars and waste 10-45 days of classroom time each year to administer them? More if you consider the amount of days spent in test prep?

What creative ideas might Sean have been cooking up at 10 p.m. on a cold Wednesday night to excite his kids about reading and learning if he hadn’t been wandering down this loopy labyrinth? Would he have been drafting a lesson plan for those kids to develop their writing and communication skills through writing their own poetry? Maybe he just would have been catching an extra hour of sleep to feel energised for the colossal task he is faced with every day, turning on adolescents to reading, writing, and learning.

Maybe by leading kids to poetry instead of force feeding it to them, Sean could have helped them sort through their own neuroses, helping to become better adults and see themselves as something other than a test score, as worthless as a leftover bath.

But we can’t know that, because at 10pm on December 13 2016, Sean was writing to me, trying to decipher misleading test prep materials he’d been handed to ready his kids for a test they will take sometime next spring.

I may be neurotic, but this is crazy.

But then, what do I know. I can’t answer the questions on my own poetry. Read below:

STARR Test, Grade 7 2014

Let’s take these questions one at a time:

32 Which lines from the poem best suggest that the speaker’s situation is temporary?

F Doubtful,/I have a fever

G Tomorrow,/I’ll come around

H TODAY!/It hit like a thwop of mashed potatoes

J I could attract mosquitoes—/maybe—not friends.

I’m guessing G, but I could make a pretty good argument for H as it (all caps) belongs to today. Mustn’t over-think this, clock’s ticking. Let’s go with G.

33 What is the most likely reason that the poet uses capitalisation in line 6?

A To highlight a problem the speaker experiences

B To stress the speaker’s expectations for tomorrow

C To indicate that the speaker’s condition happens unexpectedly

D To show the speaker’s excitement about an upcoming event

Could be A. All caps is a way to highlight a fact, right? I guess I wanted to stress the fact that the feeling belongs to TODAY, but maybe the answer is B. Let’s see, today is not tomorrow, could be that. But climbing into the test maker’s mind, I’m guessing they want the answer C. But here’s the thing: I remember adding the ALL CAPS during revision. Was it to highlight the fact it arrived today or was it to indicate that it happened unexpectedly? Not sure. Move on, lots to cover.

34 Read the following lines from the poem.

The poet includes these lines most likely suggest the speaker –

F does not wish to be pushed on a swing

G wants to deal with the situation alone

H does not often receive help from others

J is not physically strong

1. Definitely G. I don’t like being pushed around, especially on a mood swing. Or maybe F and G, clearly the speaker doesn’t want anyone in her space, pushing her around. Right? F, G, or wait, how about H? Exactly. Pushing me around when I’m in a mood is not helpful, but people do that all the time. Cheer up. Get that look off your face. Not helpful. J is just stupid, but is it a trick? (What happened to choice I? Where is I? Who am I?)

35 The imagery in lines 16 through 19 helps the reader understand –

A the shift in the speaker’s attitude

B the speaker’s unpleasantness

C why the speaker has no friends

D what the speaker thinks of others

Where is E, all of the above? C. Incoming dog breath has no friends. That’s obvious. Or B. Unpleasant yes, but that’s kind of an understatement. And of course there’s an argument to be made for A, I did shift into this mood TODAY. It wasn’t there yesterday. I obviously am not thinking much about others, that’s true (D), I was pretty much into myself and I was having a bad day.

36 The poet reveals the speaker’s feelings mainly by –

F using similes and metaphors to describe them

G explaining their effect on others

H connecting them to memories

J repeating specific words for emphasis

Now I really need that all above option. Yes F, using similes and metaphors in description. Righto. G, the phrase “could attract mosquitoes, not friends” is a pretty sure indicator my lousy mood had a bad effect on others. H? How else except through memory would I conjure up nasty dog breath and a terminal case of split ends? And then there’s J, repeated words (today, today, today). This one was the real stumper. Total guessing game on this one.

My final reflection is this: any test that questions the motivations of the author without asking the author is a big baloney sandwich. Mostly test makers do this to dead people who can’t protest. But I’m not dead.

I protest.

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments