A brief history of dyslexia and the role women played in getting it recognised

Dyslexia affects up to one in 10, but until recently it was thought to be a pseudomedical diagnosis used by parents to explain their children’s poor performance in reading

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dyslexia affects up to 10 per cent of the population and is widely accepted as a learning difficulty that can cause problems with (among other things) reading, writing and spelling. But it hasn’t always been this way.

In fact, it wasn’t until quite recently – in 1987 – that the UK government announced that they were dispelling “a myth”: the myth that they did not believe in dyslexia. The government said that it “recognises dyslexia and the importance to the education progress of dyslexic children … that they should have their needs identified at an early stage”.

“Once the assessment has been made, the appropriate treatment should be forthcoming.

The story of how dyslexia came to be recognised in the UK is a story in which women were at the forefront – as advocates, teachers and researchers. And it’s also one that’s largely yet to be told.

Word blindness

The earliest references to (what we would now call) dyslexia came in the late Victorian period, when several doctors first identified “word blindness”. Otherwise able children were showing pronounced reading difficulties.

Today, reading and spelling difficulties are still considered central to dyslexia, but other skills are believed to be affected, too. These includes motor coordination, concentration and personal organisation.

The “link” to intelligence has also been lost. It’s now recognised that dyslexia can occur across the spectrum of intellectual abilities.

Interest in dyslexia waned between the World Wars, but emerged again in the early 1960s with the creation of the Word Blind Centre in 1962.

The centre brought together several researchers, including the neurologist Macdonald Critchley and the psychologist Tim Miles, who had encountered dyslexic children in their work.

The centre closed after a decade, but its principal director, Sandhya Naidoo, published one of the first major studies into the condition, Specific Dyslexia, in 1972. Her book, along with Critchley’s The Dyslexic Child (1970), were landmarks in early research.

During the same period, larger organisations were being founded to help dyslexic children. In 1972, the British Dyslexia Association was formed, principally by the efforts of Marion Welchman. This brought together several smaller regional associations, leading to Marion being dubbed the “needle and thread of the dyslexia world”.

In the same year, the Dyslexia Institute was created by Kathleen Hickey and Wendy Fisher. And in 1971, the Helen Arkell Centre also opened.

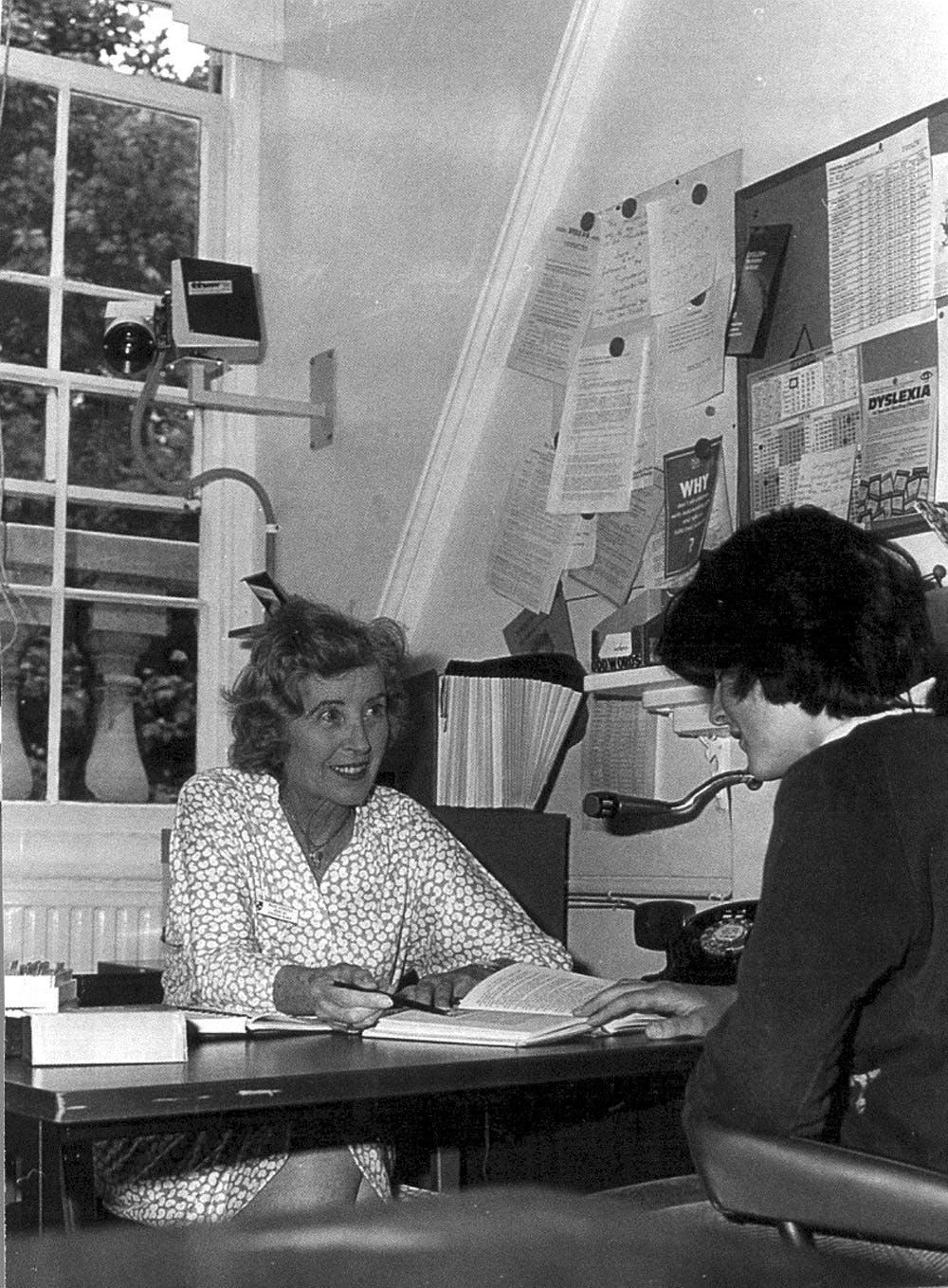

Bevé Hornsby, the “grande dame” of dyslexia, became head of the Word Blind (later Dyslexia) Clinic at Barts Hospital the same year. Dyslexia was now on the map.

A mother’s motivation

The motivation for these pioneers was often personal. Marion Welchman had observed the lack of provision (and sympathy) at school for her dyslexic son, Howard. For Wendy Fisher, it was the similar experience of her dyslexic daughter, Sophy. Helen Arkell grew up with dyslexia, and was first diagnosed by the Danish dyslexia pioneer, Edith Norrie.

After moving to the UK, Helen was asked to help the child of a friend with similar difficulties, and from there it continued. As she explained: “More and more people came, and before I knew it I was teaching quite a lot of people.”

This somewhat ad-hoc but highly effective approach was shared in schooling and research. In the late 1970s, for example, Daphne Hamilton-Fairley, a speech therapist, was increasingly encountering dyslexic children. As numbers grew, the children’s parents offered to support Daphne in founding a specialist school. Fairley House became (and remains) one of Britain’s few specialist dyslexia schools.

Daphne said: “It was magic from the point of view of parent power, and how they’ll fight for their children.”

Growing evidence base

The 1970s also saw research on the condition expand. The Language Development Unit at Aston University opened in 1973, under Margaret Newton. And the Bangor Dyslexia Unit at Bangor University was officially opened in 1977, by Tim Miles and his wife, Elaine.

Again, achievements were predicated on improvisation. Ann Cooke, later director of teaching at Bangor, recalls that part-time workers, mostly women, “were all paid on pinkies” – claim forms that you put in either every month, or every half term. Together with others, they built an evidence base for the existence and diagnosis of dyslexia.

Driven by parents and those with direct personal experience of the condition, the history of dyslexia mirrors that of other conditions, like autism.

Against an often antagonistic political atmosphere, these women, together with male counterparts, drove progress. They did so through a unique intersection of care and emotional engagement, alongside formal research, advocacy and study.

At the University of Oxford, a team is charting a comprehensive history of the condition, uncovering the stories of these women, who helped to get dyslexia recognised. And in the current climate, where there are challenges to funding for special educational needs, the story of dyslexia’s pioneers serves as a warning against the gains that could be lost.

It also shows how women – during a period when they were largely excluded from formal political spheres – found other ways to achieve support and recognition for children with dyslexia.

Philip Kirby is a research associate in the faculty of history at the University of Oxford. This article was first published in The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments