Could Beyoncé do for the coronavirus vaccine what Elvis did for polio?

In 1956, Elvis Presley was recruited to help persuade huge numbers of teenagers refusing to take the polio vaccine

Beyoncé could help, it's been suggested, as could Tom Hanks or The Rock. Or maybe an athlete instead. Serena Williams, perhaps, or even Michael Jordan?

As millions of Americans continue to express reluctance or outright refusal to get vaccinated against the coronavirus, the country's political and public-health leaders are pondering a question critical to ending the pandemic: Who can change their minds?

When the federal government faced a similar dilemma more than a half-century ago, it had a king at its disposal.

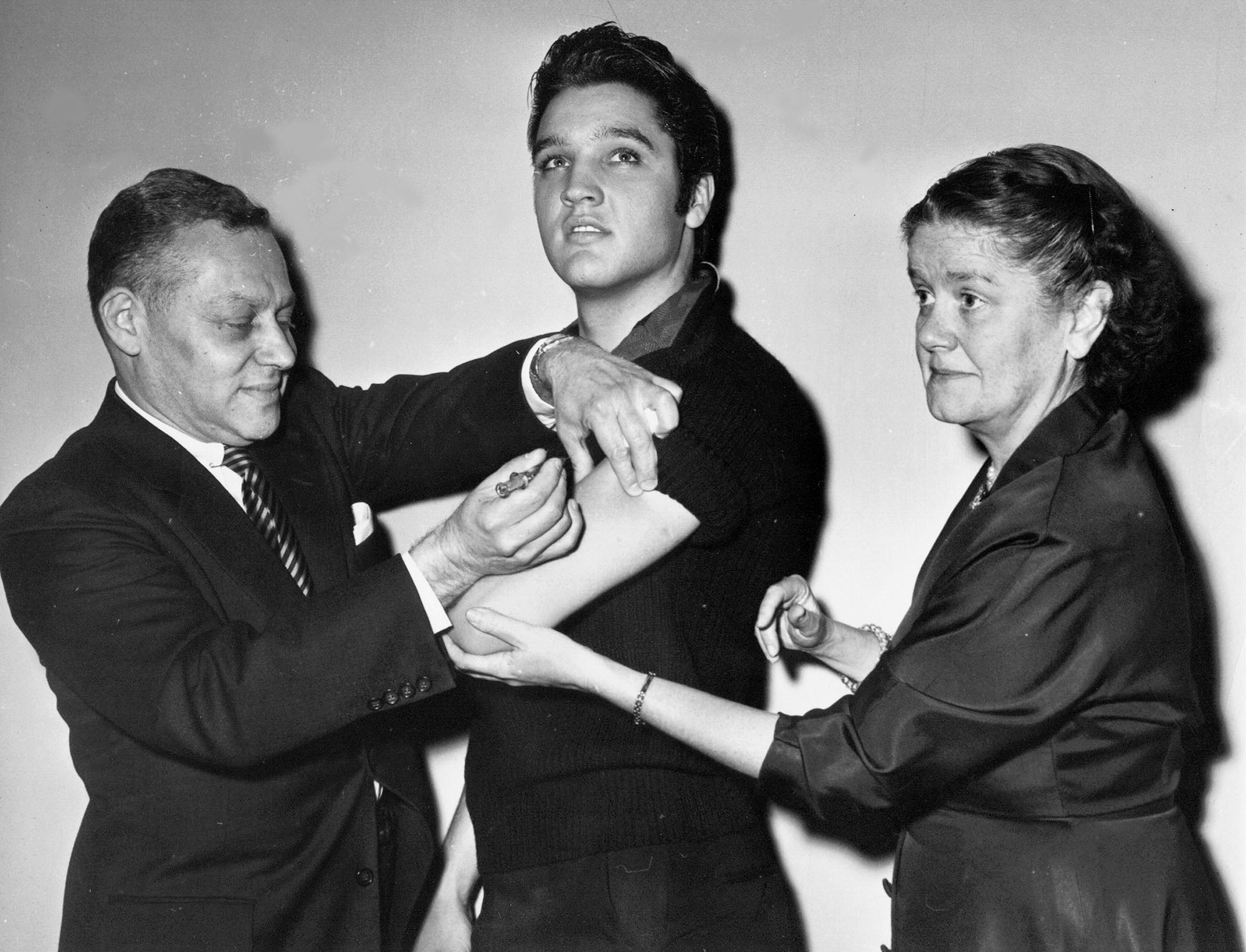

In 1956, a huge number of teenagers were refusing or neglecting to get the polio vaccine developed by Jonas Salk. So the March of Dimes recruited Elvis Presley, then 21 years old, to help. He agreed, smiling as he received an injection during a photoshoot just before he played “Hound Dog” on the Ed Sullivan Show.

“He is setting a fine example for the youth of the country,” one of the doctors involved said, because that was the point. Just 10 per cent of New York City’s teens had received an inoculation at the time – a full year after the vaccine’s debut. Later, young people who got their shots were given a photo of Elvis getting his.

Elvis was an influencer long before the term was coined for the current generation of YouTubers and Instagrammers, but who has the right influence with the right people (namely, the resistant millions) isn't easy to pinpoint. The previous, current and soon-to-be presidents have all been raised as potential promoters, as have professional athletes, pop stars and the ultimate 2020 celebrity, Anthony Fauci, who will turn 80 years old this month.

On Friday, the vice president, Mike Pence, received a vaccination on live TV along with second lady Karen Pence and the surgeon general, Jerome Adams.

In the UK, Sir Ian McKellen, 81, and The Great British Bake Off judge Prue Leith, 80, have received and lauded the vaccination as part of the country's effort to recruit “sensible” celebrities whose embrace might sway public opinion.

This is not a new strategy, there or here; since the United States’ inception, the country has relied on its most famous citizens to persuade people reluctant to accept new treatments, according to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. After Benjamin Franklin lost a son to smallpox, he pushed variolation, a method of immunisation in which people were infected with a mild form of the disease to protect them from being killed by it.

Today’s celebrities are better known for thwarting public safety causes – Jenny McCarthy, Jessica Biel and Jim Carrey have opposed mandatory vaccinations – but how much clout they or any another famous people have is a point of debate.

This month, a viral tweet implied that Elvis’s staged photo op was the primary reason that millions of teens began to get the polio vaccination in the late 1950s, but that's not entirely true, according to Stephen Mawdsley, a historian at the University of Bristol who has studied the episode and its effects.

Elvis had a marginal impact, Mr Mawdsley said, but the breakthrough came when the March of Dimes invited teenagers to an office in New York to explain why their peers weren’t getting vaccinated. The organisation learned that some were afraid of the needles, others couldn't afford it, and many viewed themselves as impervious to illness (a reminder that teenagers haven’t changed that much in the past 60 years).

But after the conversation, the March of Dimes did something even more important: it asked the teenagers to join it in promoting the cause.

They agreed, forming “Teens Against Polio”. The group asked popular students to get their shots in front of classmates and held “Salk Hops” that only welcomed boys and girls who could prove they’d been vaccinated.

“They advised that print material for teens needed to be concise and 'written by teens, for teens, with teen language,’ ” Mr Mawdsley explained in the journal Cultural and Social History. “To be attractive, they suggested pamphlets employ pictures and catchy slogans, such as ‘Don’t Balk at Salk. Roll up your sleeve, Steve. It's the most.’”

Fearful students were labelled “fraidy cats”, Mr Mawdsley said, and some young women adopted a “no shots, no dates” policy in which they refused would-be suitors who'd yet to be vaccinated.

The strategies worked, Mr Mawdsley said, and by the late 1950s, polio cases had dropped by about 90 percent since the decade began.

The challenges facing public health officials today will be considerably more complex, Mr Mawdsley acknowledged. There are people of every race, age and political allegiance who have said they won't take the coronavirus vaccine. Even so, he said, the lessons of past decades remain relevant in this one. If America's leaders want to persuade those groups, they need to recruit their members to help in the effort rather than relying entirely on faraway celebrities to change minds.

“Today, if we have a demographic in a similar situation, include them,” he said. “When you connect with people and you listen to them and not talk down to them, you probably have more in common than you realise.”

The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies