How supermarkets use particle physics to save thousands of tonnes of food waste

AI company Blue Yonder uses science developed at Cern for the Large Hadron Collider to predict exactly how much of every item shoppers will buy each day

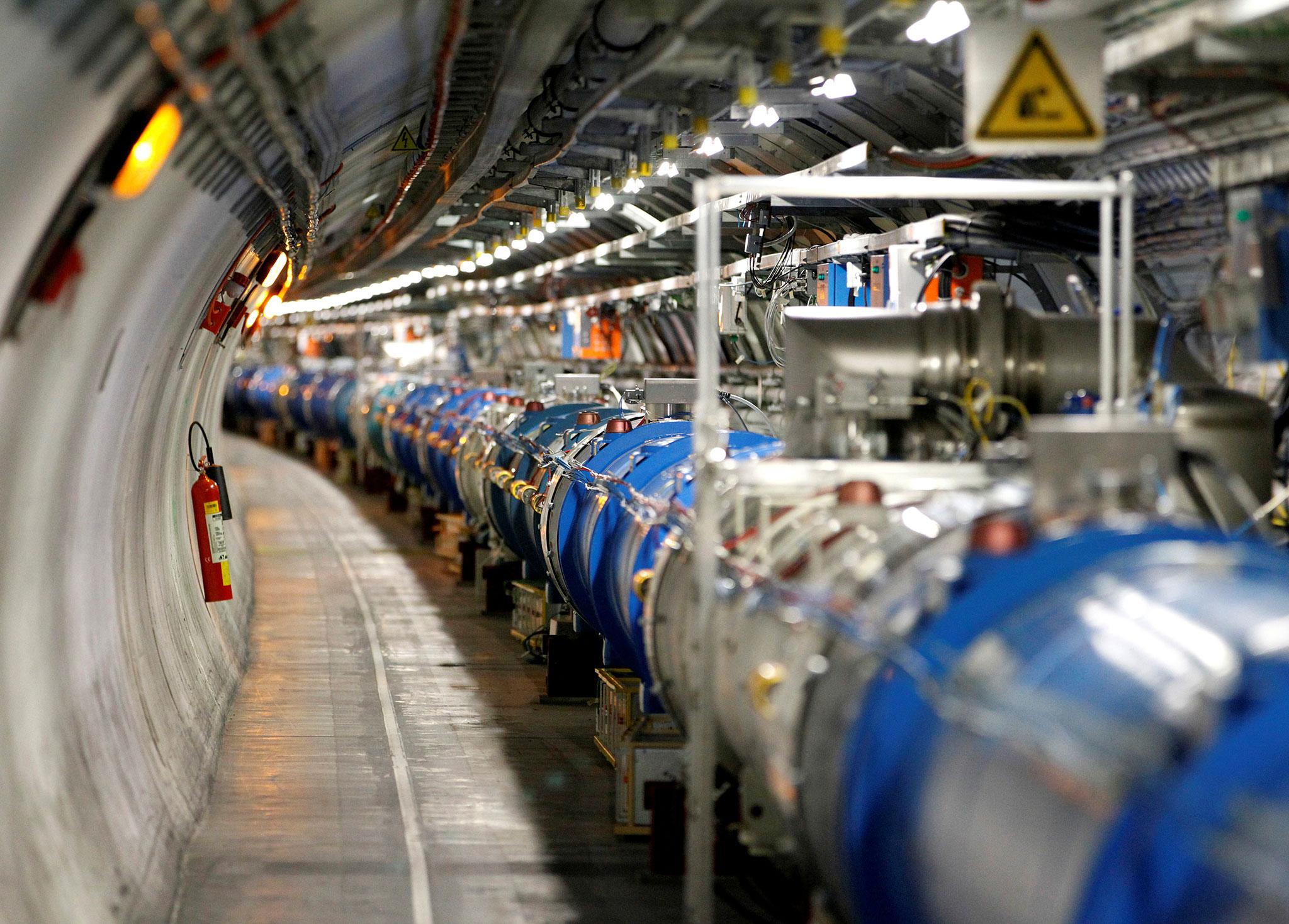

Supermarkets are using particle physics developed for the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator – the Large Hadron Collider – in their battle to save thousands of tons of food waste.

The technology is also a vital weapon in the race to keep up with online giants like Amazon in an increasingly competitive retail market, says Professor Dr Michael Feindt, founder of AI firm Blue Yonder.

Professor Feindt originally created the NeuroBayes algorithm to predict the activity of quarks – the building blocks of matter – while working at Cern, the world-leading research centre in Switzerland. It was only later that he realised the potential of his work to revolutionise retail.

Now Morrisons is using it to make much more accurate predictions about exactly what stock it needs, and drastically reduce the amount of food that is thrown into landfill. Used to its full potential, Blue Yonder’s system can make efficiency savings of up to 30 per cent, says Professor Feindt.

UK supermarkets threw away around 235,000 tons of food in 2015 according to a report by Government-backed charity, Wrap.

“What we are doing is very similar to what we did at Cern – we observed hundreds of millions of collisions and found a model that described what happened. This is quite similar to how the algorithm learns for a large retailer.”

Billions of pieces of data on past shopping transactions and stock levels, along with other information such as live weather forecasts, are fed into the algorithm, which then makes around 16 million decisions every day for Morrisons. It gives shop managers the exact probability of how much of each of the tens of thousands of individual products will be sold on a given day. The algorithm then learns as more data is gathered each day.

Human beings can override certain aspects of the system – for example if a store is running a big promotion in line with a sporting event or holiday period – but the computer is vastly more efficient at making day-to-day stock decisions, 99 per cent of which can be automated, he says.

Even very experienced shop managers simply cannot calculate all of the variables for different products, such as shelf life, delivery times and spikes in demand, that are required to accurately predict what a supermarket needs.

“This also frees up time for people who would have been doing unfulfilling tasks in front of a computer, [like] going through many lines of items, clicking ‘yes’ or ‘no’,” Professor Feindt says.

“If a person has to do this for 20,000 items, it simply doesn’t work, they just go for a default option.”

Blue Yonder’s algorithm breaks down decisions to the finest grain possible, the Professor says, so that supermarkets can cut waste while also ensuring they don’t run out of stock. However, there is always a trade-off between the two and ultimately the supermarket makes the final decision.

Blue Yonder can also change the prices of items based on demand and stock levels. Such dynamic pricing has attracted some controversy, but Profesor Feindt says there is no need for concern.

Online retailers regularly change their prices without people noticing and fashion chains also move prices up and down depending on how popular a particular item has been in a given season. Such tactics are widely accepted and have proved successful.

Generally, supermarkets won’t be shifting prices on a daily basis and he says the overall cost of a shopping basket is unchanged on average.

Blue Yonder has already implemented dynamic pricing at Otto, one of Germany’s largest retailers. After extensive interviews, it found that consumers did not notice the price changes. In fact, companies who have used Blue Yonder’s system have attracted more new customers by ensuring that the items people want are in stock at the right price and the right time.

“Importantly, none of our price changes are targeted specifically to individual customers,” Professor Feindt says, as this would be likely to cause uproar.

The key to the success of Blue Yonder, says Professor Feindt, is its ability to successfully combine the highly technical world of physics and machine learning with the more mundane environment of grocery shopping.

Business news: In pictures

Show all 13“Artificial intelligence is very much talked about right now but what you find is that there are a limited number of people with those skills and most data scientists are very nerdy. We convert nerd into retail and then retail back into nerd.”

The worlds of nerd and retailer will increasingly have to work in harmony, the Professor says, as competition from online giants squeezes already tight margins for traditional bricks-and-mortar shops.

“At Amazon and Google, for example, everyone uses artificial intelligence but retail is a very different world.

“It is essential that they convert from the traditions of a long-established company that didn’t have to think like this until now and transform into an AI, data-driven company.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies