Sean O'Grady: Credit crunch: 'It's just the end of the beginning'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

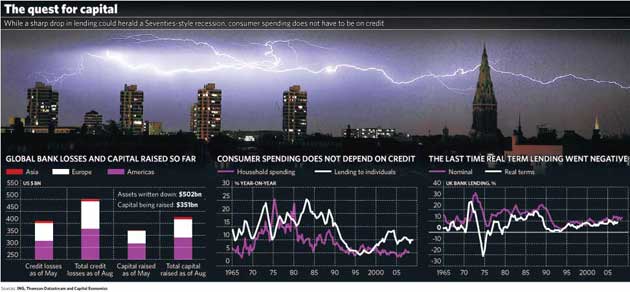

Your support makes all the difference.Here's some "big picture" numbers on the state of the world's financial system. According to ING, the total value of assets written down by Planet Earth's big banks is $502bn. The total value of capital raised by the same: $351bn. That deficit, of $151bn could easily get much much bigger. No wonder the Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, Charlie Bean, said the other day that the slowdown may "drag on for some considerable time", while the IMF has called it "the largest financial shock since the Great Depression".

Now, shortly after the unhappy first birthday of the credit crunch we are at what we might call "the end of the beginning". Even though Ken Rogoff, a former chief economist at the IMF, has chillingly warned that a "whopper" major bank will go under in the next few months, at least we know the rough parameters of the sub-prime problem – usually neatly and memorably rounded to about $1 trillion ($1,000bn). It may even be a little better than that: house prices are still falling in the United States, but mostly at a gentler pace. So some of the gloom may be lifting over there.

What's next? Well, there are two new looming threats to keep us awake at night. First, the certainty that what one might term the "normal" writedowns and losses associated with an economic downturn will add to the strains on banks' balance sheets just when they are at their weakest.

In the UK, we know these are on the rise because some banks have already declared such difficulties; because of the rising trend of redundancies, arrears and repossessions; because of the collapse in sentiment in the housing market and because the first-round effects of the credit crunch are now creating their own second-round effects, through the "mortgage famine" for first-time buyers, the main source of new funding to the residential property market.

That, by the way, is now being exacerbated by a fall in demand for new mortgages from those same first-time buyers, who judge that a falling market is one where they can afford to rent, wait and see. No matter, though; the picture is one where more people will find it more difficult to service their debts, from credit cards to car loans and mortgages, the banks will have to wait longer for their money and may see some of it lost for good.

Which brings us to the second nightmare. Will the banks be able to raise the capital required for them to regain their strength as losses mount? Now for the banks what we've seen is rather like suffering from a bad case of flu (sub-prime) and then catching a cold (normal downturn losses) on top. Result: financial pneumonia. For which the well-known cure is plenty of liquidity fed to the system by assiduous central banks (see the Bank of England's patent Special Liquidity Scheme among other miracle cures) and a strong course of capital injections.

The latter is proving steadily more tricky to administer, as we see from those big numbers I quoted at the beginning and from the rights issue flops at HBOS and Bradford & Bingley, among others. It has been a laborious task even to raise the £20bn the British banks have now garnered for their balance sheets. The team at Capital Economics calculates that £65bn more is needed in the way of fresh capital, that is if the banks are to carry on functioning at their current rates of lending and to sort out the remaining damage from the credit crunch.

Alternatively, the banks could simply reduce their lending. But that would mean an even bigger brake on growth than we have seen so far. Capital Economics says that for the banks to correct their balance sheets in this manner would imply a reduction in lending of £440bn (17 per cent of the balance sheet), a truly terrifying sum. Some mixture of the two seems more likely, but even that has some nasty consequences.

If the banks manage to raise another £20bn from disposals, conventional rights issues, Sovereign Wealth Funds in China and the Gulf subscribing for equity, and stake building and takeovers by foreign banks relatively unscathed from the mess (e.g., Banco Santander/Alliance & Leicester), this would still mean a contraction in balance sheets of £180bn, or 7 per cent – equivalent to 13 per cent of the UK's GDP. I mention that just to illustrate the scale of the phenomenon, and is not meant to be a read off for the wider economic effects. Much of the contraction in lending will hit foreign entities, and bank credit is not the only source of spending in the economy. That is, despite appearances in recent years; some rebalancing away from our reliance on debt to fund growth is overdue and welcome, though it will be painful.

However, if UK bank lending drops by just 5 per cent, that will easily be enough to tip the economy into recession. Capital Economics says that it would mean business investment also down by 7 per cent, that housing market activity would "grind to a halt" with a 50 per cent drop in prices, and consumer spending down by 1.4 per cent, shaving 0.6 per cent off growth per annum, where it is already expected to be stagnant. We last saw real terms lending by the banks go negative in the mid 1970s – not a happy precedent. So recession here we come.

Is there a way out? Well, things may not turn out to be as bad as the pessimists anticipate. But a third option, not up to the banks but available to the regulators, internationally, would be to ease the banks' capital requirements, altering the ratios to allow them to lend more on thinner capital, so-called "counter cyclical" regulatory action. Risky, perhaps, but maybe more welcome than their fourth option, of direct state intervention to support lending. That, we can confidently say might well be the beginning of the end.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments