What does the Kobe Steel crisis tell us about the mismanagement and operation of big business?

The Kobe Steel crisis should not be viewed in isolation. Poor operational governance is widespread and it impacts us all

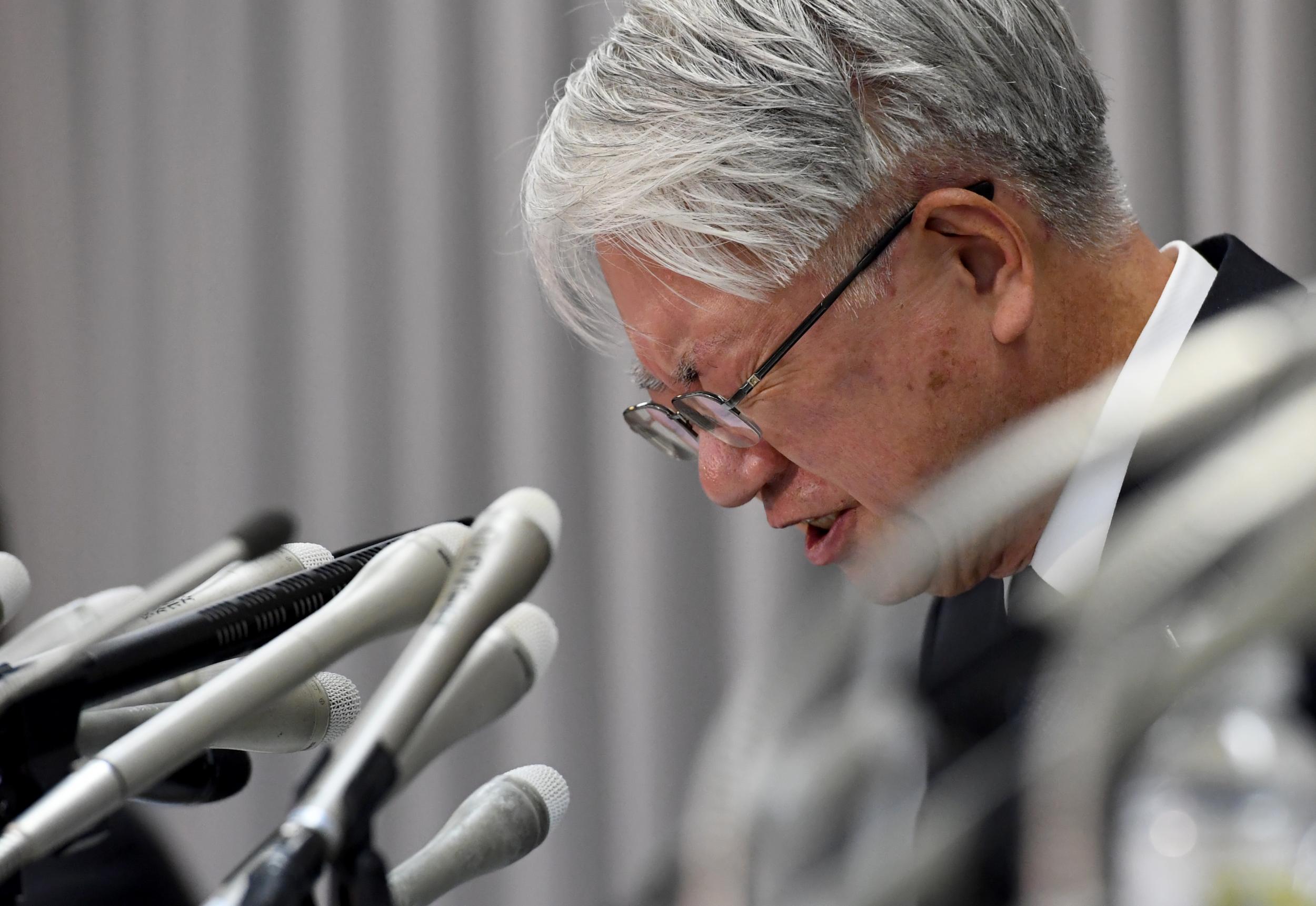

The latest development in the Kobe Steel crisis saw CEO Hiroya Kawasaki resign earlier this week, following the publication of a report into failings that led to the falsification of inspection data for aluminium, copper and steel parts used in a variety of safety-critical industries.

While the resignation itself sends a strong message about ultimate responsibility, there are still huge questions to be answered, not least of which is: what has been done to ensure that the falsification practices, which date back to the 1970s, have actually stopped?

Echoing investigations into the recent collapse of Carillion, one of the key findings of the report is that pressure to secure new contracts meant that orders were accepted, without consideration for whether they were possible within the company’s production capabilities.

Thanks to a management style that “overemphasised profitability” and allowed for “insufficient quality control procedures,” orders were accepted and delivered upon for which Kobe had no way of meeting the assigned specification.

As with recent controversies such as Carillion or Volkswagen, this demonstrates a widening gulf between the board and the operation of business - what could be termed a failure of operational governance.

At Kobe Steel, the falsification of data appears to have become the norm - an accepted practice that has been neither questioned nor reported. This is a cultural issue, which also falls under operational governance, because it is the responsibility of the board to set the standard for organisational culture and to know that it is being adhered to.

The publication of the report itself and the fact that Kobe Steel is now being so open about its failings is extremely positive.

More widely, the report highlights the need for boards of all companies to ask themselves a series of questions about their own cultures and practices for example:

Are quality assurance procedures in place that make it near impossible for people to fail to do things the right way?

Whether standards are achievable or, in the case of Kobe Steel, “utterly impossible to conform to?”

Is your business operating in a series of silos or is there an integration between departments, such as sales and production?

What measures can be introduced to ensure that communication is two-way and not just top-down?

Are whistleblowing employees treated as nuisance troublemakers or an early warning system and a valuable part of the feedback loop?

Crucially, can whistleblowers bring matters to senior managers and the board, without fear of losing their jobs or being denied a promotion?

These questions can only be answered if the board of directors is willing to widen its own remit and take a more holistic view of their companies and their own responsibilities. The board sits at the apex of an organisation and is all-too-often removed from day-to-day operations, but the answers to these questions will be found in the body of the organisation, not in the audit and remuneration committee.

While there has been a demonstrable impact on the businesses that have been caught in these scandals, it is all of us who pay the ultimate price, whether through the safety concerns associated with lower quality metals in our planes, trains, automobiles and infrastructure, the health impacts of increased pollution, or disruption to public services.

The time has come for boards to act to ensure that their businesses are operating, both in line with long-term sustainability aims, and in a way that is meeting the demands placed on them by customers, staff and society, as well as investors. An investor only approach, where the needs of these wider stakeholders aren’t taken into account is doomed to failure. Without such action the likelihood of another Kobe Steel, Carillion or Volkswagen crisis is almost inevitable.

Estelle Clark is Director of Policy at the Chartered Quality Institute.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies