Hamish McRae: The Italians and Americans are hardly in a position to lecture Germany on how to run its economy

Economic View: Eventually there will have to be some kind of split in the eurozone

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Noël Coward wrote his controversial song "Don't let's be beastly to the Germans" in the spring of 1943 he was being satirical, as some of the other lines make viciously clear. Thus: "Though they've been a little naughty/To the Czechs and Poles and Dutch/I can't believe those countries/Really minded very much."

But now bashing the Germans is back – and it is both unpleasant and unwarranted. You can understand that people in the countries squeezed by austerity and suffering years of ever-falling output as a result resent what is being imposed on them and want to lash out.

Germany, lead choreographer of their "rescues", is the obvious target for their anger. It is less easy to understand the criticism of people who are not directly paying the price for their leaders' past folly.

This week, the former EC president and former Italian prime minister Romano Prodi said that Latin countries should unite against Germany and force through a reflation of the eurozone economy.

It was strong stuff: "France, Italy, and Spain should together pound their fists on the table, but they are not doing so because they delude themselves that they can go it alone," he said.

"German public opinion," he continued, "is by now convinced that any economic stimulus for the European economy is an unjustified help for the 'feckless' south, to which I have the honour of belonging. They are obsessed with inflation, just like teenagers obsessed with sex...

"Today there is only one country and only one in command: Germany."

You get the drift. But it is not just frustrated Italians who are attacking the country.

Last week the US Treasury produced a report that blamed poor eurozone growth squarely on German policies.

The key passage was: "Germany has maintained a large current account surplus throughout the euro area financial crisis, and in 2012, Germany's nominal current-account surplus was larger than that of China…."

It continued: "Germany's anaemic pace of domestic demand growth and dependence on exports have hampered rebalancing at a time when many other euro area countries have been under severe pressure to curb demand and compress imports in order to promote adjustment."

I have not seen an official German response to the charge that its electorate's attitude to inflation is akin to a teenager's about sex, but its finance ministry has rebuffed US criticism of its economic policy.

"There are no imbalances in Germany that need correction," it stated. "On the contrary, the innovative German economy contributes significantly to global growth through exports and the import of components for finished products."

There are obvious retorts to Italian and American criticism. As far as Italy is concerned it is to ask why a country with a national debt of 130 per cent of GDP and unemployment at 12.5 per cent should feel it appropriate to attack one with debt of 82 per cent of GDP and 6.5 per cent unemployment. As for the US, the equivalent numbers are less grisly but being lectured by a country that came within a whisker of a default on its debt last month, does rather stick in the craw.

Actually there are imbalances in the German economy, for the current account surplus this year is equivalent to 7 per cent of GDP. The issue is why this should be so. Is it that Germany is artificially restricting domestic demand or is it that the German people prefer to save their money for their retirement rather than blow it now? Are German exporters so successful because they squeeze down the wages of their workers or because they produce goods the rest of the world wants to buy? Is German fiscal policy too tight – they have just got back to a balanced budget – or it the country being prudent in getting debts under control, given its ageing population and the need to get in shape ahead of the next global recession?

There are no conclusive answers to these questions. It is very hard to criticise Germany for running its economy relatively well. Do you really want Germany to make a mess of things?

But the fact that Germany is following responsible policies does put pressure on countries which have been less responsible in the past.

My own view is that the problem is not German policy as such, but the rigidities imposed on Europe by the euro.

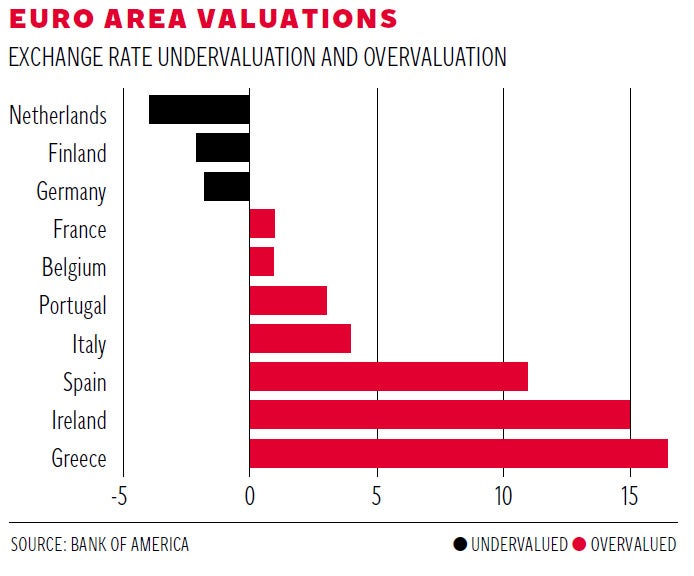

One way of looking at this is to see to what extent individual countries are overvalued or undervalued in their membership of the euro.

Some calculations by the International Monetary Fund and Bank of America Merrill Lynch are shown in the graph. The currency as a whole is reckoned to be a bit above its stable level, but as you can it is far too high for Greece, Ireland and Spain, but a little too low for Germany and the Netherlands.

Some conclude from this that Germany is getting an artificial boost to its exports from a competitive currency, but actually the fact that German costs are low has been the result of a decade of grind by German people and businesses. Germany joined the single currency at too high a level and has only managed to gain its present, competitive edge by relentlessly squeezing down its costs. The problem is the one-size-fits-all monetary policy.

So what will happen? Germany is not going to change, at least not radically. The country's new coalition government, when it is agreed, may ease up a bit on wages policy, perhaps by agreeing a minimum wage. But it will not tolerate higher inflation. So the rest of Europe has to adjust to it.

This will continue to be extremely painful – a generation of jobless young people across a whole swathe of Europe. Eventually there will have to be some kind of split in the eurozone, but a little growth and political will may prevent that happening for several years yet. Not good, even for the (largely blameless) Germans.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments