Hamish McRae: The case for higher rates: A better supply of more expensive money is needed

Economic Life: Two things have to get back to normal: interest rates have to rise and we have to unwind the flood of money caused by quantitative easing rates

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As a general rule in the world of finance, things take longer than you would expect to happen, and then when they do move, they happen more suddenly.

And so it is with interest rates. The present ultra-low rates are unsustainable. They would be unsustainable in a period of low inflation but they are especially unsustainable with inflation, however you measure it, approaching 5 per cent.

There are perfectly good reasons for delaying the forthcoming rise in UK rates for another three months – for what it is worth, I happen to think the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee is right to hold off – but nothing will stop the forthcoming rise in global interest rates.

And I'm worried that the rises, when they come here and elsewhere, will be sharper than anyone thinks.

Or maybe not. I came across a new fact the other day. For many years, the top New Years resolution of Americans was to lose weight. In 2009, for the first time, it was to pay off debt. So maybe there is some awareness in the United States that we are in abnormal times and that rates will soon go up.

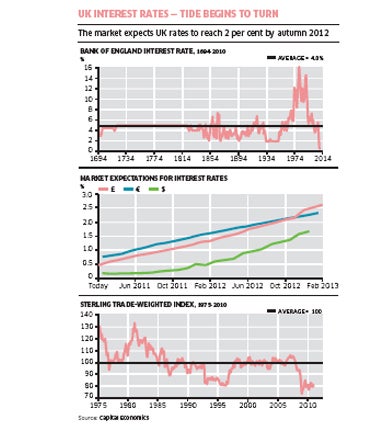

At any rate, as you can see from the first graph, official interest rates in the UK are lower now that at any stage since the Bank of England was founded. Wars, the Industrial Revolution, the creation and loss of empire, bank crashes just as serious as the recent one – all these seismic changes within our society occurred without interest rates being driven down to their present levels. Indeed, this recent recession, though serious, is following almost exactly the same profile as that of the early 1980s. It is serious, to be sure, but not unprecedented.

So what will happen next? A good starting point is to look at market expectations. You can work out what the financial markets think will happen to short-term interest rates at various dates in the future by looking at overnight swap rates. This is not what people say – or think – will happen, but rather, what they bet their money on when it comes to future events. You can see on the middle graph the projected increase in rates over the next two years for dollars, euros and sterling.

As you can see, both sterling and the euro follow a steady path upward, with overnight rates predicted to be 2 per cent by October next year. It is not quite a prediction of how the Bank of England and the European Central Bank are expected to increase their official rates but it is close enough to that, because overnight market rates are determined by official rates.

US rates are quite a bit lower than sterling and euro rates: the markets think the Federal Reserve will tend to hold back. That may turn out to be right, though I worry about the implicit assumption within the US that the rest of the world, and China in particular, will cheerfully continue to lend it the money to finance its deficit. There must be at some stage be a sudden loss of confidence in the US of its ability and willingness to service its debt unless there is a radical change of policy.

Anyway, the upward path is clear enough. If you were to look at similar calculations for Chinese or Indian rates, or indeed those of any other major currency, a similar pattern would emerge. Money is going to become more expensive everywhere.

What does that mean for us here? Well, there are two things that have to get back to normal: not only do interest rates have to rise; we have to unwind quantitative easing, that flood of money pumped into the system by the Bank of England's buying of gilts from the market. That has depressed longer-term rates. Put crudely, because the Bank has bought the gilts, the Government has been able to fund itself more cheaply than it otherwise would. But long rates are now rising too and have been since last autumn. So you don't want to bang up longer terms rates any faster than you need to, but you have to set out some path to normality or people lose faith in our ability as a country to manage our affairs.

Sterling is very weak by the standards of the past 30 years, weaker even than after the ejection of the pound from the ERM, as you can see from the bottom graph. It may be convenient to have an under-valued currency at this stage of the cycle, but it has had more of a knock-on effect on prices than I think the Bank of England expected and I suppose it is also, in some measure, a testimony to the fragile state of global confidence in the Government and the Bank of England.

That leads really to the core issue: are the Government and the Bank still in control? There are a number of people who argue that the real issue is what the Government should do about economic growth. That presumes that the Government can do something about growth in the short term, which surely flies in the face of all evidence, particularly if the policy is simply to borrow more. The last government borrowed more as a proportion of GDP than any other major country but we still ended up with one of the most serious recessions of any.

No, the issue is whether the authorities are still in control. As far as the Coalition is concerned the answer is surely yes. It is unpopular and will become more so but governments that have to do difficult things ought to be unpopular. Governments that just roll the problems forward may be popular at the time, but are eventually exposed.

As far as the Bank is concerned there is more of a worry. There is a lot of stuff around of a hostile nature. I don't think anyone will take seriously ad hominem attacks on the Governor, of which the most odd was one in The New York Times earlier this week. I am not quite sure what it has to do with the US – except in the sense that it was the US that exported its subprime crisis to the rest of the world. But the thoughtful comments from DeAnne Julius, one of the original members of the Monetary Policy Committee, who is now chairman of Chatham House, are worth taking seriously. She said that the Bank needed to tighten policy "sooner rather than later" or risked loosing credibility.

A lot of people will agree and it will be interesting to see, when they are published, the minutes behind yesterday's decision to hold rates.

In any case, availability of finance is more important than price and it may well be that a better supply of somewhat more expensive money will do more for the economy than present ultra-cheap rates. Better to have slightly higher rates soon than risk having much higher ones in a couple of years.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments