Hamish McRae: Greece can look to Britain for exit directions

Economic View

So now it is an odds-on bet. The saga of the travails of the eurozone took another twist last week, with Germany's finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble, saying that the eurozone would cope if Greece were to leave the currency union, and with a Bloomberg opinion poll showing that a majority of investors, traders and others involved in finance expect Greece to leave by the end of this year.

We have moved in the space of a few months from an outcome that was either unthinkable or at least most unlikely, to something that is deemed probable and acceptable. It is rather like the break-up of the Bretton Woods post-war fixed exchange rate system. A mechanism that was deemed essential to prevent a return to the currency chaos of the inter-war period and therefore must be protected at all costs, resisted the initial challenges but eventually was beaten by inherent weaknesses in its design.

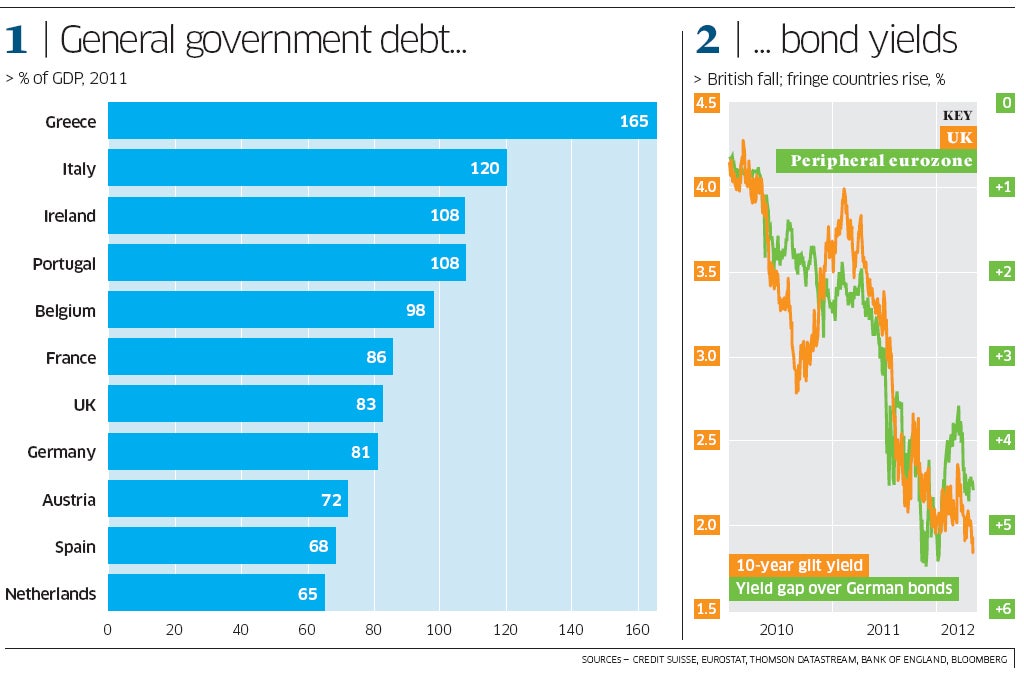

As we all know now, and the Germans identified at the time, there were weaknesses in the design of the eurozone. One of those was the way it enabled weaker countries to borrow much more cheaply than they would have been able to do outside the currency union. The result was predictable. As you can see from the main graph Greek indebtedness is way outside any sort of acceptable zone when compared with other European nations.

So we have gone beyond the "what should happen?" question to the "what will happen?" one, and the next question is "how will it happen?" What will be the mechanism of a country leaving the eurozone and what might the consequences be?

It is impossible to see the detail but we tend to forget that the world has a lot of experience of currency unions breaking up. As far as the mechanism is concerned, we have the experience of the break-up of the transferable rouble used by the central and eastern European countries in the Soviet empire, which was pretty chaotic, but we also have the break-up of the currency union between Britain and Ireland in March 1979, which was remarkably benign. That experience probably provides the best template for a currency leaving the eurozone.

The Irish Currency Act of 1927 had established a fixed link between the Irish pound and sterling. For more than 50 years the two currencies had been completely interchangeable and British notes and coins circulated in Ireland alongside Irish ones. When the link was broken by Ireland, bank balances in Ireland automatically remained as Irish pounds, while contracts written under Irish law were in Irish pounds too. Contracts under UK law remained in sterling.

Initially it had been expected that the Irish pound would rise against the British one but actually it fell: by the end of 1980 the Irish pound was below 80 pence sterling, the sort of devaluation many expect were the fringe eurozone countries to leave. But you could say in the case of Ireland that this was more the result of the UK pound rising than the Irish one going down, for sterling had been pushed up by rising North Sea oil output, and the Irish pound had been locked into the European exchange rate mechanism. Indeed the primary reason why the link with sterling was broken was Ireland decided to join the ERM and Britain did not.

So there is a precedent. A country could leave the eurozone over a weekend, converting all bank balances into, let's say, "new euros". All contracts written under national law would be converted. So people would still be paid in these euros, prices in the shops would remain the same, property deals would go ahead in the new currency. Some imports and exports would be under local law and others under international law and so there would be a scramble to sort those out.

It would be messy, but no more messy than it was in Ireland in 1979. People in Britain (including the many Irish ones) who held assets in Irish pounds and suddenly saw them devalued in sterling terms were pretty aggrieved, but there was nothing they could do about that. By contrast Irish people who had British bank accounts had a windfall gain, at least until sterling fell back again, as it duly did.

There would however be one practical difficulty that did not apply then. Ireland already had its own notes and coins and British ones were quickly withdrawn from circulation. Since there are no "new euros" and since "real euros" would be hoarded, any country leaving the eurozone would have to move fast to get new currency into people's hands. The time-honoured method is to overprint existing notes stating these notes were new ones. I suppose that might happen. In practice it might be easier to wait for new currency to be printed. Memo to travellers to southern Europe this summer: take plenty of spare cash, including pounds and dollars, just in case...

There would inevitably be a devaluation of the new currency vis-à-vis the old, for the whole economic purpose is to enable the country leaving the eurozone to become more competitive. The fact this might happen is now being priced into the markets.

A final thought. Last week not only saw a shift in views about the durability of the eurozone. It also saw a flood of money into the so-called "safe havens" of British, German and US government debt. This flood has driven the yield on UK 10-year gilts to the lowest in our history. You can see that on the right hand graph. But note too how fears about the fringe of Europe have moved almost exactly in tandem, for as our long-term yields have tumbled, so the premium a fringe European country would have to pay over and above Germany has risen.

The fringe for these purposes excludes Greece and is defined as Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Italy. Capital Economics, which did the calculations, points out that as tensions in peripheral eurozone government debt markets increase, UK gilt yields fall.

So you could say that the markets feel that this has already gone far beyond Greece. How quickly would a Greek exit open the door for more to follow?

The Bank needs to explain to us why inflation is so high

The UK's safe haven status would be more comforting were it supported by a better economic performance, for the other two main countries that have benefited from an inflow of funk money, the US and Germany, seem to be delivering somewhat stronger growth.

This week we can expect to get further confirmation of the strength of the US recovery, with some manufacturing surveys and industrial production figures, and Germany seems to have escaped the recession that the eurozone as a whole is experiencing.

But here? Well, the thing that will be most interesting will be the state of the labour market: has employment held up? We get some figures on this and while the unemployment numbers are always the ones that understandably take the headlines, there will be other data that will tell us more about what is happening here.

The great puzzle is the discrepancy between employment and hours worked and GDP. Technically we are in recession, but employment has been recovering, albeit very slowly.

So does this mean that productivity is falling? It that were true it would be deeply discouraging, for ultimately we can, as a society, only increase living standards by increasing productivity.

Or are the GDP figures understating what is actually happening by more than some of us think? The Bank of England's next quarterly Inflation Report comes out on Wednesday and that always provides a focus, not least because the Bank's economic division provides an alternative perspective on the economy.

There is no escaping the fact that the UK has had substantially higher inflation than either the US or the eurozone and, I think, we as a country need a better account of why the Bank thinks this has happened than we have been given to date.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments