Hamish McRae: Europe has to play to its many strengths

Economic View

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What can Europeans – and let's just accept that Britons are Europeans – do that others cannot do just as well or better?

This, surely, a much more important question than the row over the European budget, the machinations by the European Central Bank to save the euro, or all the other European stories that people fret over.

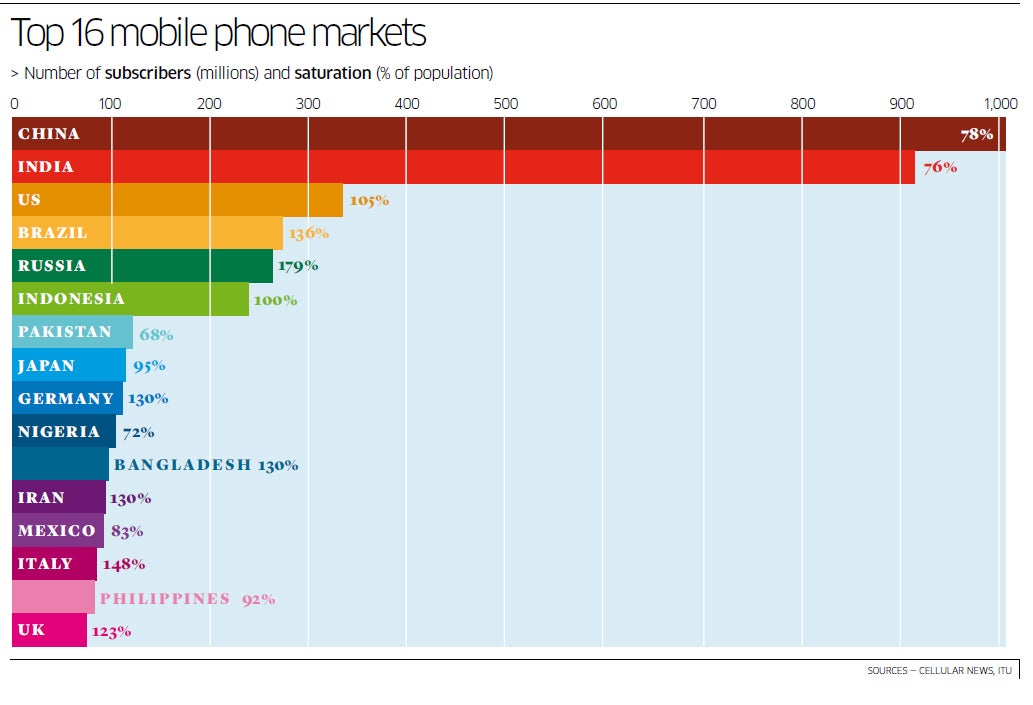

It is a question that came to me when I was looking at the graph, right. It shows a snapshot of mobile telephony at the end of last year – both the numbers of subscribers and market penetration. As you can see, four of the top five are BRICs, while European nations only creep on to the bottom of the stage. We come in at number 16.

It is true the so-called advanced world probably has more complex phones, though I suspect our lead is not as great as we think. It is true, too, that the US, in particular, leads in design and software, though the kit is mostly made in China. But if you take mobile telephony as a proxy for the way the world economy is heading it must be a worry. It is more of a worry for Europe than the US, because it seems able to innovate at a faster rate than we do.

So where does Europe lead, aside from welfare payments? (The EU produces about a fifth of world output but spends half the world's welfare budget.) It might seem a dispiriting question, but if you start totting up what Europe is good at, the list is encouragingly long. We are uneven, but so too is every other region, and the best in Europe is very good.

Any tally of excellence is subjective and the subject is huge but it might be helpful to set out some areas and ask how durable they are. Let's start close to home. One just-published statistic shows China took 11.5 per cent of British car exports last year, up from 1.5 per cent five years ago. That is by value, not volume, for the cars the People's Republic buy are mostly Land Rovers, Rolls-Royces, Bentleys and Jaguars.

That is one success story, bringing the UK balance of payments in cars back almost to surplus, and it carries three wider lessons. One is the obvious one, which applies particularly to Germany rather than the UK, that top-end automotive engineering is something that Europe can do best. The reason Germany is Europe's most successful economy is its success as an exporter to the emerging world. You can broaden that to include other types of specialist engineering, including medical equipment, aeronautics and so on. That pulls in other countries, including France, Italy and Switzerland – and especially Scandinavia.

The second lesson is that where a product is associated with a top-end brand, be it a car, a watch, a fashion line, a wine, whatever, European products command a premium. The re-emergence of luxury brands has been one of the extraordinary features of the past decade, driven principally by demand from the BRICs. It depends a bit on how you define it, but something like three-quarters of the world's luxury brands, as opposed to the upper-middle-market brands, are European.

The third lesson is the openness of the UK, but also much of Europe, to foreign investment, including from the emerging world. That is what has revived the UK motor industry, with Tata of India a shining star, succeeding with Jaguar Land Rover where previous owners had failed. But it is also happening elsewhere in Europe, with, for example, Chinese owners saving Volvo in Sweden.

There is one more area of European excellence often overlooked – top-end services. These range from medical to educational. (Some Britons find it hard to acknowledge their private-sector schools are the world's largest exporters of secondary education.)

They include property and financial services, including wealth management, and entertainment and culture. As so often in Europe, the pattern is uneven, with the UK and Switzerland more important in financial services than Germany, and with France dominating travel services.

This leads to what is perhaps the biggest issue of all. How does Europe integrate what it does best with enterprises and consumers in the emerging world? This is partly a question of access to capital, as three-quarters of the world's savings come from Asia. It is also access to markets and to tastes. In other words, by having foreign investment, European enterprises gain access to the tastes of those markets. You keep the integrity of your brand but tweak it to suit local tastes. There are lots of examples of that: Scotch whisky developed just for the Chinese market, and so on.

If there are unique European strengths, different ones in different countries, there are also massive challenges. The great gnawing question is whether these areas of excellence are big enough to employ an inadequately educated workforce. I fear the answer may be no.

One of the heart-breaking aspects of Europe now is the extent to which the burden of our relative economic failure has fallen disproportionately on the young. Some countries are coping better than others – Sweden and Switzerland, for example – but the eurozone leads the global league table in unemployment. This seems extraordinary for a region where, in some countries, the size of the workforce is declining. The issue is to what extent this is the result of policy failures or a function of weak European competitiveness. My instinct is that it is more the former, or at least I hope so – bad policy is easier to fix.

But the message, surely, is Europe has unique strengths and whatever one's view on the competence of its politicians or the EU's structure, those strengths should be nurtured. But, we must also recognise we will matter less in the world, as we already do in mobile telephony, witness the graph.

Year of the Snake promises much for China, but research says not

It is a sign of the times that the Chinese New Year is starting to attract almost as much attention as the Western one. After all, the Chinese economy will probably add as much to global demand as the US, maybe more. So will the Year of the Snake be a boom, a bust – or a slither?

By tradition, snakes are auspicious for wealth creation. They don't carry the Adam and Eve connotations that we attach to them; rather they are cautious and canny, setting good conditions for saving and investment.

The year is projected to be one of somewhat slower growth, but still close to 8 per cent, which by Western standards would be stunning. Thus, Professor Qing Wang, of Warwick Business School, argues that although it is slowing the mass transfer of people from the land to the cities will drive growth for years to come.

This optimism is echoed by Coutts's wealth management arm, which feels this will be a bright year for Chinese equities, noting that price/earnings ratios would suggest shares are cheap by comparison to other markets. Barings also reckons that shares will have a less bumpy ride than they did last year, noting that in Chinese mythology: "While snakes might be perceived as materialistic creatures, preferring to surround themselves with the best life has to offer, this often means they work harder and go that extra mile to achieve their objectives."

If all this sounds a bit too good to be true, a rather more sober assessment has been done by Colin Cieszynski of CMC Markets. He has looked at what has happened in previous years of the snake and I am afraid the news for financial markets as a whole is not so good. They come round at 12-year intervals, so the last one was 2002, slap bang in the middle of a bear market. They have been particularly bad for Chinese shares if you take the Hong Kong market as a measure, with shares down four cycles on the trot. However, with the exception of 2002, UK shares have tended to go up in snake years, so I am not quite sure what conclusion to draw, expect perhaps to wait for the next Year of the Pig.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments