Hamish McRae: Dubai crisis will prompt investors to look critically at sovereign debt

Economic Life: Dubai made the classic mistake that the maturity of the debt did not matter as it could always be rolled over

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is a Dubai story and there is a wider sovereign risk story. The first is straightforward enough; the second, more complicated, more important and more interesting.

The Dubai story itself comes in two parts. One is the economic proposition that it makes to the world, the idea that it is possible to create sustained growth by becoming an entrepôt trading and service centre for the Gulf region. That is the justification behind the port, the airport, the banking offices, the medical centre and so on. This determination to become the service hub for the region led to the property boom, indeed was the only justification for it. As everyone knows, things got a bit out of hand. The "build it and they'll come" approach is all very well but it left Dubai vulnerable to any drop in demand. Ultimately Dubai will recover because the core proposition – that the region needs high-quality services – still stands. But there will be a nasty and continuing adjustment for some years and the more outlandish building projects may never be completed.

The other part to the Dubai story concerns finance. On any sort of long view its public finances will be all right. This is not an Iceland. It has assets, including a sizeable sovereign wealth fund. The United Arab Emirates, taken as a whole, has massive oil-generated wealth and that wealth will continue to accumulate as it is very hard to see circumstances when oil will not remain reasonably expensive. But Dubai itself is caught in a classic liquidity squeeze. Property development is its biggest business and this has happened countless times in the property game. Think Canary Wharf here in Britain. But as we have learnt so savagely over the past year, this is a world where assets are at a discount and cash is king. The world is not through this squeeze yet and the financial pressures on Dubai will mount further.

Nevertheless the effective default has led to a shock. You can see that in the global market reaction. That raises the inevitable question of the Queen: why did people not see this coming?

The answer is that to some extent they did. Standard & Poor's downgraded its credit rating on some of the big government-related companies last March. It did however assume that the government would stand behind these government-supported banks and companies, an assumption that now seems to have been over-optimistic. Everyone, too, assumed that Dubai's much richer fellow emirate, Abu Dhabi, would make sure there was no hint of default, and that was over-optimistic too. Much of the problem is timing: the structure of Dubai's debt is short term, for it has made the classic mistake that the maturity of the debt did not matter as it could always be rolled over. It is not alone in making that assumption, but the consequences are particularly serious.

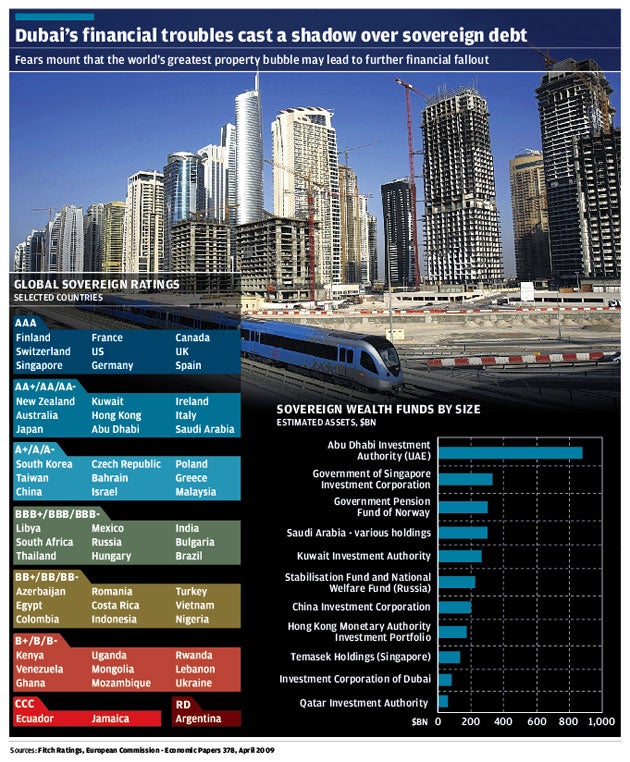

That leads to the sovereign risk story. It is complicated because it has so many elements to it. There is the conventional credit rating system, and I have put on the right a list of selected countries, showing their credit ratings. I have taken the Fitch ratings as they pioneered country risk analysis, particularly among the emerging economies, though they have not done a rating on Dubai. As you can see, there is a clear hierarchy from Finland to Argentina, starting with the AAA countries at the top. The UK for the time being still carries that rating. The agencies take in a huge amount of data when assessing countries, going far beyond the actual size of the debt and rate to which it is being added or paid down.

There are many difficulties, though, with this sort of exercise. There is the rear-view mirror problem: that the agencies have to work with the data they have got and things change. No one, two years ago, could have predicted that Britain was on course to double its National Debt. But more important still, when it comes to a country rather than a company, is that this is not just about accounting: political will is crucial. If countries wish to cut their debts, they can almost always do so, because they have the tax base of a nation to deploy. Companies are different, for they can go bust in a way a sovereign country cannot.

Now have a look at the bar chart on the right. That shows the top sovereign wealth funds, the national funds that countries have accumulated and invested on behalf of their citizens. And number one is, wait for it, Abu Dhabi. So Dubai's neighbour is, on this measure, the richest country in the world. Now have a look a little further down the list and there, at number 10, is Dubai. Huh? What is all this about? A lot of us would have wished that the UK had used its oil wealth to build up such a fund as Norway has done. Most people would assume that any country with a large pile of assets would be a secure place to which to lend. But the import of this list is to suggest that even countries that do build up such funds and therefore have a strong asset position can still run into trouble if they miss-manage the debt side of their balance sheet.

I am not sure how this will play in the coming months but I have a nasty feeling that this threatened default by Dubai will make investors scrutinise sovereign risk much more critically. People who have assumed that Dubai was rock-solid, partly because of its own stock of assets but more particularly because of the resources of Abu Dhabi, have been proved wrong.

So what does this mean for Greece, whose debt position is probably the weakest among the eurozone members? As you can see it is in the middle rank of creditworthiness. But there is, I think, an implicit assumption that the rest of the eurozone countries will support it if it gets into difficulties: Germany will pick up the tab. Well maybe it will, but what should the premium be for the risk?

There is a further twist. What happens at the moment when ratings are downgraded is that the borrowing costs rise a bit but not that much. I wonder whether all sovereign debt will now be more sensitive to rating changes, or even warnings of the possibility of these. To come right back to home, we should be concerned here in the UK if we lose our AAA rating, as indeed we may next year. The US rating is by no means secure either.

The main developed countries will emerge from this crisis with debts of on average 100 per cent of GDP. For the moment the markets take on trust that the countries will have the political will to service those debts and make a start on cutting them back. But they took on trust that Dubai would have that political will. We have hardly begun to see the consequences of this ballooning of public debt, but I am sure that this will become a real concern from now on. Things could get ugly, and they could get ugly fast.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments