Hamish McRae: Bricks, Bric and risk are changes to come from the US debt crisis

Economic View: Over the next few years investors will seek to shift to real assets rather than financial ones

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is hard, amid all the political noise from Washington, to pick out the economic signals. How will we look back on this episode in, say, five years' time? Will it be analogous to the collapse of Lehman Brothers, where the failure to co-ordinate a rescue made what would have been merely a nasty recession into something much worse?

Or is our own rescue of Royal Bank of Scotland (which had been, don't let's forget, briefly the largest bank in the world) a better template, where as someone at the centre of things put it to me: "we didn't do it well, but we did it well enough"?

As of last night, it looked as though the deal might just squeak by as "well enough". But maybe what is happening is more akin to the double-digit inflation of the late 1970s, and with it the collapse of confidence in the entire global monetary system. The world, led by Paul Volcker at the Federal Reserve, did eventually restore monetary discipline, but at huge social and economic cost.

What is happening now is not only about the willingness of the US to service its debts; it is also about the ability of other developed countries to do so, countries as significant as Japan and Italy.

The concept that binds together willingness and ability is "sovereign risk". The US can service its debts, at least for the next few years, but there is the political risk that it might not do so. It might, for example, choose not to service debt held by China were the relationship between the two superpowers to deteriorate when China passes the US as the world's largest economy.

Japan, on the other hand, almost certainly will be unable to service its debts in a few years' time and the only issue will be the form of the default. Italy is in much the same position. It also faces the prospect of a declining population and though its debts are smaller as a proportion of GDP, unlike Japan it does not have control of its currency. Look forward a decade and I cannot see how either country can avoid default.

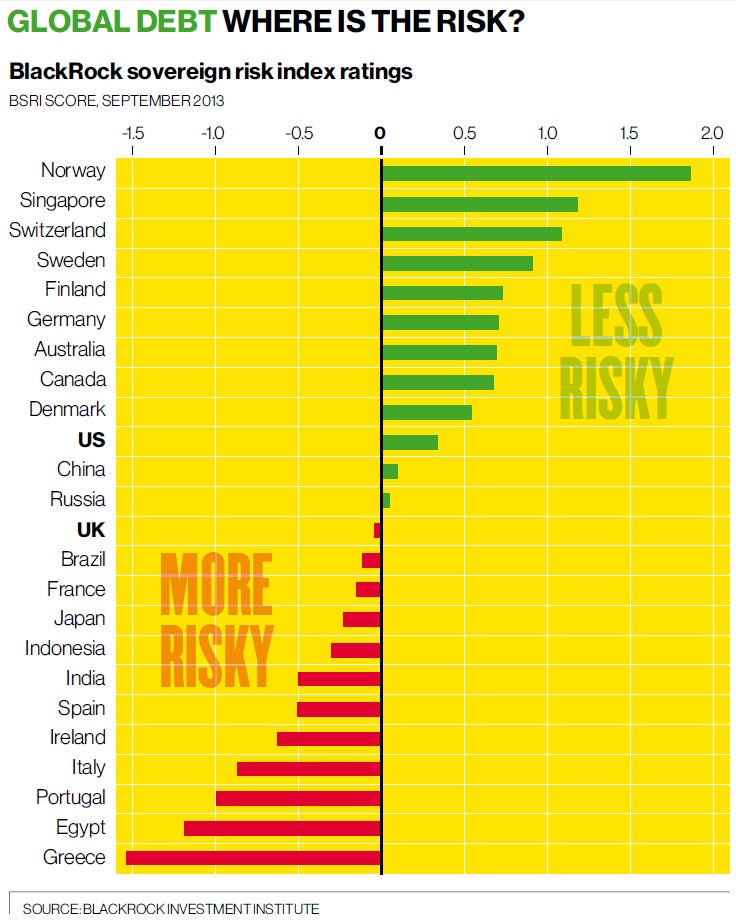

A useful ready-reckoner of sovereign risk is produced by BlackRock Investment Institute and I have shown a simplified version of the update it published yesterday in the chart. At the top of the league, the country least likely to default is Norway, followed by Singapore, Switzerland and Sweden.

The US is middle of the pack, ahead of the UK, which is (and this is bit of a shocker) below China and Russia.

Unsurprisingly at the very bottom comes Greece, but note too how low Italy, Spain, Ireland and Portugal come.

This list is not meant to forecast the creditworthiness of countries. It is just a model that pulls together various factors: the size and maturity of a country's national debt, an assessment of its willingness to pay, its balance of payments and the amount of debt held abroad, and the security of its banking system.

Nor do these assessments align with those of the bond markets, for Japan is still able to borrow at very low rates, while Australian bond yields are quite high (the 10-year is 4.25 per cent) despite its relatively strong performance on this index.

None of this is yet accepted by the financial markets. Bond yields are still very low by historical standards, though they have come up a long way over the past 18 months. What we don't know is why they are still so low. Is it that they are artificially depressed by the various forms of quantitative easing?

Or is it that banks and other financial institutions are compelled to hold public debt for supposedly prudential reasons? Or is it the absence of perceived alternative investments? Or something else?

What we do know is that the mood of the bond market can shift suddenly. Irish 10-year yields topped 11 per cent in the summer of 2011; now they are below 4 per cent.

So the question seems to me to what extent the current US debt machinations shift the view of global investors away from holding sovereign debt. Does this speed up the "great rotation" out of fixed-interest securities and into equities and property? We are one year into what some of us think will turn out to be a 30-year bear market in bonds, so we may lurch rather further along that path than even the bond bears expect.

Or we may not. Of course a lot does depend on the outcome of the next few hours and the Senate deal yesterday bodes better. But if you stand back, it is odd isn't it that investors all around the world should be in thrall to a few hundred politicians in one city? They are important sure, but rationally not that important. My guess is that whatever happens in the next few days there will be three lasting legacies.

One is that over the next few years investors will seek to shift to real assets rather than financial ones. In the first instance that will benefit equities and property, but looking further ahead there will be a variety of new ways of investing in something solid, rather than something that is merely a number on a computer screen. The buzzphrase of the moment is the "hunt for yield"; the next one will be a "hunt for solidity".

A second is that holders of assets will want to diversify between countries to a much greater extent. The US will account for a smaller proportion of total portfolios of course; so too will Europe. Instead the focus will be inevitably on the Brics, but increasingly on the fast-growing middle-income countries, what Goldman Sachs dubbed the "Next 11".

And the third is investors will have to work much harder in assessing where risk lies. What is currently perceived as risk-free is not risk-free and what is seen as risky may actually be quite secure.

So a big rethink of the whole investment game; and a long overdue one too.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments