Hamish McRae: As its population ages and inflation stalls, Europe is becoming more like Japan than it might like to admit

Economic View: The reason Japan stagnated is because it did not want to make structural reforms

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mario Draghi says it isn't; many people fear it will become it; and would that be so bad, after all?

The proposition is that Europe will become the new Japan. It is not a new idea at all, but it has been given legs by the rising fears that one aspect of the Japanese economy over the past 25 years – persistent deflation – is in danger of becoming embedded in the eurozone.

Mr Draghi was seeking to tackle that possibility when he said that the European Central Bank needed a "safety margin" when tacking deflation. We learn today whether there is any significant shift in ECB policy in response to this danger.

At the moment the eurozone is still some way from outright deflation. The latest figures, for November, show annual inflation for the region as a whole at 0.9 per cent, up a touch from 0.7 per cent in October. But while in Germany inflation on the harmonised basis was 1.6 per cent, in Spain it was only 0.3 per cent (after zero in October). But you can understand the concern, particularly for the highly indebted periphery, which need some inflation to help reduce the real value of their debts. In any case the whole region is well below the ECB ceiling of 2 per cent, so it has room to move.

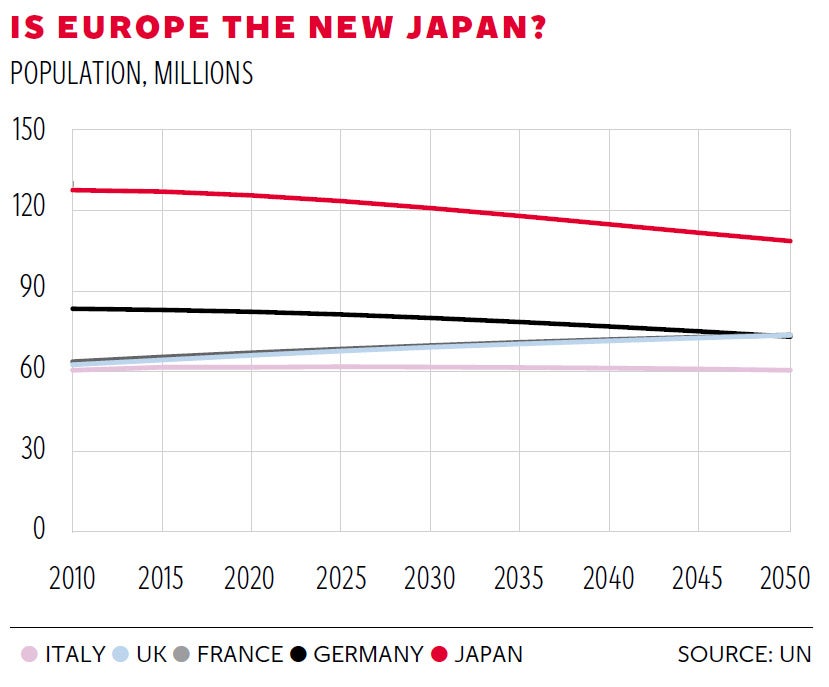

However, while deflation is naturally the aspect of Japan's economic predicament that the ECB focuses on, there are other ways in which Europe is coming to resemble Japan, of which the most obvious is demography. Or rather parts of Europe: I have shown in the graph the most recent UN projections for the population of Japan through to 2050, plus those of Germany, France, the UK and Italy. Japan is projected to fall from 127 million at present to 108 million. Germany is rather similar, falling from 83 million to 72.5 million. But Italy is projected to stay at around its present 60 million – though the age structure will be very different, while France and the UK are both projected to increase from around 63 million to 73 million – ie to become about the same size as Germany.

Now these are just projections. A lot can change. Strong job markets suck in people looking for work, while weak ones force them overseas.

In the case of the UK we seem already to be well past the 64 million mark, a level we were not expected to reach until 2016. France, too, is well past 64 million, at least if you add in Corsica.

So in population terms Europe is not the new Japan. Germany is, or at least will be unless its relative economic success sucks in large numbers of immigrants. Italy may become it if, as seems to be happening now, large numbers of young people leave for jobs elsewhere.

But France and the UK are heading in the other direction.

There is, however, a third dimension to Japan's relatively stagnant economy: the lack of structural change. That takes many forms. In Japan the issue is partly regulation, from restrictions on the retail trade and immigration, to protection of farmers and other special interest groups.

But it is also something deeper and very understandable: a desire to protect a lifestyle. Japan is safer and cleaner than just about any other country in the world and it is perfectly adequately prosperous. Why change?

If you look at Europe through Japanese eyes, you can see elements that are familiar particularly in Germany. There are also examples of the desire to protect what is seen as a special lifestyle, for example in France. But if you take Europe as a whole, there are certainly places that look outward rather than inward, with Switzerland, Scandinavia, Ireland and the UK at the top of the list.

The UK in particular differs sharply from Japan both in its attitude to immigration and its relationship with the rest of the Anglosphere. We are also very capable of generating inflation, perhaps rather too capable in that regard.

I think the central point here is that what has happened in Japan is largely the result of a choice of the Japanese people. There was an out-of-control property boom, the aftermath of which was bound to be a drag on growth for a decade. Policies were ineffective and there is a debate about why.

I personally feel the huge fiscal deficits and the ultra-low interest rates, while appropriate in the very short-run, actually inhibited what would have been a decent medium-term recovery.

But the real reason why the country has stagnated is because it did not want to make the structural reforms. It was a micro-economic failure rather than a macro-economic one.

Apply that thought to Europe. The region is a kaleidoscope. Some of the structural changes needed to make for a more competitive economy are being taken by countries on the periphery, notably Ireland.

But there are places where not a lot is happening – Italy for example. Germany, having pioneered labour market reform in the middle of the last decade, may now be relaxing again. The business mood there is quite cool to the grand coalition.

France? Hard to know, for the Hollande government is probably an interlude and the next government will take a different direction. The rigidities of the single currency and single interest rate don't help, but you cannot blame everything on the euro or the ECB.

If you focus on the narrow issue of deflation, there can be little doubt that the ECB has both the tools and the will to avoid the Japanese experience.

But this is not just a monetary matter, nor even a European Union matter – though a competent EU will be more conducive to growth than a bureaucratic one.

It is really a question of what people in Europe want. Do they want comfort and stability at the expense of growth? There is nothing wrong with that.

Or do they want something more exciting?

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments