Can we deflate the asset price bubble without a big bang?

Low interest rates and quantative easing saved us after the crash. But now all the central banks face a great dilemma

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

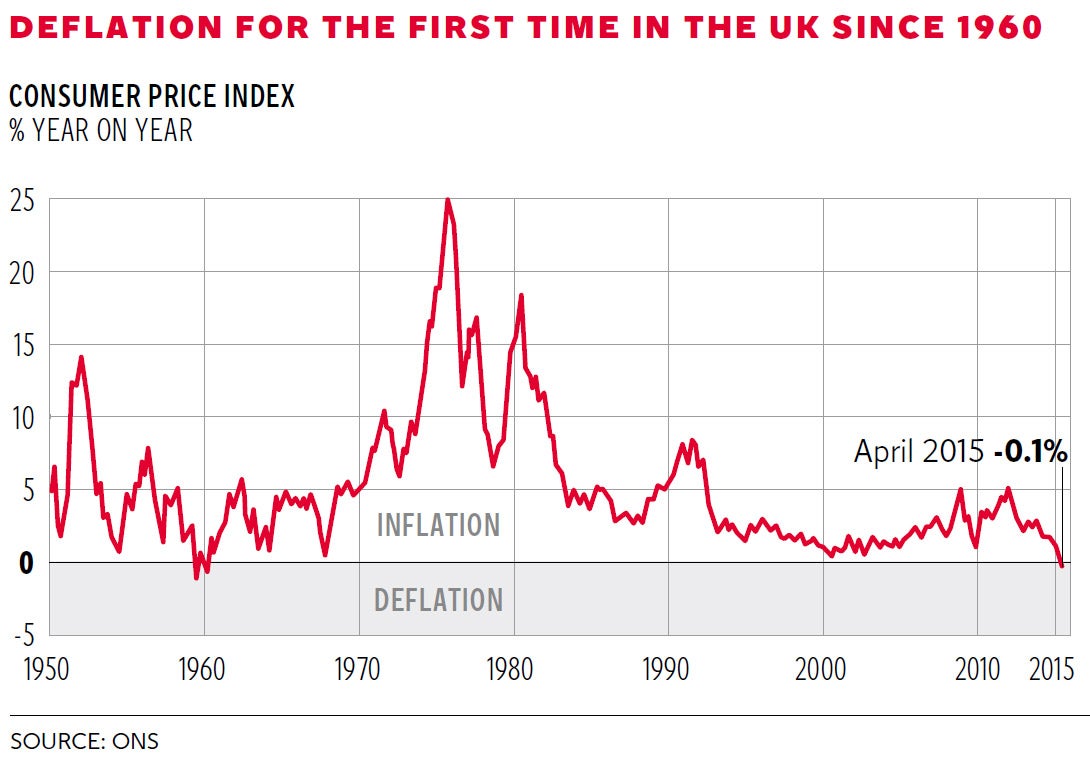

Your support makes all the difference.Just after 9.30am this morning the Office for National Statistics revealed that consumer price inflation in the year to April was down by 0.1 per cent, the first such fall since the CPI was introduced. Then, six minutes later, it published the House Price Index for March – which showed that prices in the UK were up 9.6 per cent year on year.

There you have the great dilemma facing not just the Bank of England but all the world’s central banks right now. They have managed, with six years of ultra-low interest rates and quantitative easing, to get economic growth going again. They have managed to do so without leading to a surge in current inflation; indeed, thanks to the slump in the oil price many developed countries are now, like us, experiencing deflation – falling prices. But that success has come at a price: inflated asset values. They have created inflation all right; just not the sort than many academic economists had expected.

The first question that worryingly and inevitably follows is: have the central banks created another bubble? And the second is: if so, can they deflate it gently without disaster?

The bubble first. UK house prices are just one element of a global phenomenon. What is happening in Britain looks extraordinary to us, driven as it is by tight planning restrictions on land use and the emergence of London as a safe haven for foreign money. To some foreigners a home in Mayfair is the equivalent of putting your money in gold bars: it may not bring in any income, but at least it will always be worth something. But this is not just London. In New York there is a similar hunt for trophy homes and a raft of very tall, thin towers are now being built in Manhattan to meet this demand.

Nor is it just the prices of top end homes that are racing away: US residential property in general is up 5 per cent year-on-year, which means homes have climbed by 30 per cent over the past three years. The same is happening in Germany, particularly in hot-spots such as Berlin, where prices are up by more than 50 per cent since 2009. In Dublin, prices are up 22 per cent year on year, although they are still well below their 2008 peak. Even the Spanish property market seems to have recovered a bit, notwithstanding the tales of British owners of holiday homes still being unable to sell.

Other asset classes have also done well. A Picasso sold a week ago for $179.4m (£115m) – the highest price ever paid for a work of art. If, as reported, his grand-daughter puts his former house above Cannes up for sale, the asking price of €110m (£79.5m) sounds almost a steal by comparison.

Property aside, the two main assets that really matter are equities and bonds. Global equities are current worth, to take a round number, some $75 trillion. That is double the value in 2009 at the bottom of the last recession and a bit higher than at the previous peak in 2007. The main UK index, the FTSE100, did not quite reach its previous peak then, but now it is well ahead. The most recent arrivals at the party have been German shares, with the DAX index up more than 20 per cent this year.

But whether this is a bubble is very hard to say. Some classic valuation indicators such as price/earnings ratios suggest that prices, while high, are not exceptionally so. The market pundits line up on both sides, with some arguing that the bull market has still some way to run, while others predict a crash around the corner.

What I think you can say is that to justify present share prices, the world economy has to go on growing solidly for at least another couple of years, doing so in the face of rising interest rates. But a bubble in the sense that shares are ridiculously high? Well, not really.

Bonds are a different matter. Global bond markets are actually a lot larger than global equity markets. If you add together the value of outstanding government bonds, financial market bonds and company bonds, they come to some $150 trillion. Here, something remarkable may have happened a month ago. By the middle of April eurozone bonds yields (which move inversely to prices) had been driven by the European Central Bank down to very low, often negative levels: the average yield on German debt went negative. Prices correspondingly soared. That has now turned round. The 10-year German bond yield is back up to 0.6 per cent, still very low, but at least well above zero.

The effect of this has been to push up bond yields worldwide. Our own Government now has to pay just under 2 per cent for 10-year money, whereas a month ago the rate was 1.7 per cent. This affects everything. Our mortgage rates are starting to edge up, though they are still exceptionally low. It may well turn out that there is indeed a bubble in the bond markets: that long-term interest rates are artificially low, and correspondingly bond prices artificially high.

Try this commonsense test. Is a buy-to-let property that yields 4 per cent after costs giving a fair reward for the risks involved? Most people would say it just about does. So unless you think rental rates will fall a lot, the price is reasonable. Is a portfolio of shares that gives a 3 per cent dividend yield also a reasonable return? Unless you think there is a world recession looming then that is probably okay too.

But is a return of 2 per cent on 10-year government debt – given the inflation target of 2 per cent – also reasonable? The answer must be no, because you are in effect lending the government money free.

So can the world’s central banks deflate the bond bubble gently? It would be lovely to be able to answer that question, but no one can. They will try, as they have to. But interest rates will start to rise soon, probably starting in the US, and a tricky balancing act will then begin: all we can do is keep our fingers crossed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments