Hamish McRae: Germany has got itself a new government, but how will it face the social challenges ahead?

The deal is a compromise, as it must be, and one that highlights sharply the tension within the country

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.So Germany has a government – or at least it has the crucial agreement between the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats that will almost certainly be approved by the SDP membership next month and hence lead to the so-called grand coalition of the two major parties.

The deal is a compromise, as it must be, and one that highlights sharply the tension within the country between the twin objectives of economic growth and social harmony. In these negotiations the CDU has tended to emphasise the first, while the SDP has stressed the second. So the CDU’s red lines that there should be no increase in taxation and no softening of fiscal policy have been held. But the SDP has achieved its objectives of a minimum wage, a cut in the pension age for some people, and some less important policies such as certain rent controls.

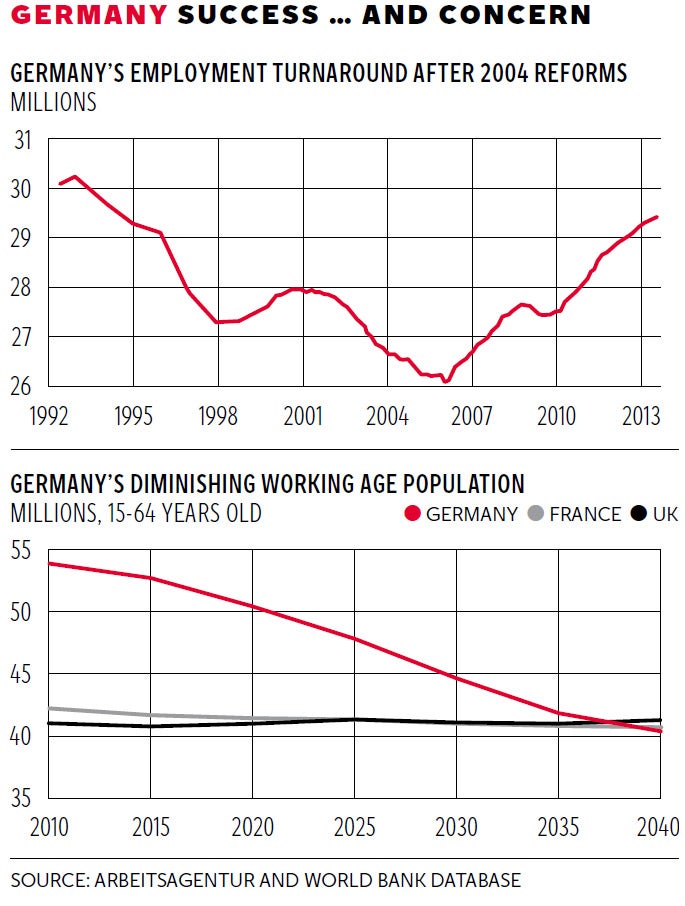

I suppose the big question here is to what extent Germany will retreat from the radical reforms that propelled it from being dubbed the sick man of Europe in the early 2000s to becoming the eurozone’s powerhouse. The most important single element of this transformation was the labour market reform that took effect in 2004. This introduced short-term contracts, encouraged part-time working and made changes to social security legislation that encouraged job growth at the cost of a reduction in worker rights. It worked. You can see the way the number of employed people turned round in the top graph.

But there was resentment. Many young people found they had to take several part-time jobs, or accept insecure ones, rather than enjoy the conditions enjoyed by people who had entered the job market a decade earlier. That resentment has built and shows in the push for a minimum wage, for currently Germany is one of the few countries in the developed world that does not have one. Ironically the SDP has been the party pressing on this, though it was an SDP government that introduced the labour market reforms. It was voted out shortly afterwards, which perhaps colours its current view.

So Germany keeps its fiscal orthodoxy. Any increase in social spending will, it is assumed, be funded by the natural increase in tax revenues. The plan is still to maintain a balanced budget and the assumption is that unemployment will continue to decline. Germany also keeps its resistance to the pooling of eurozone debt, and will maintain a stern line against future bailouts. But the prospect of further structural reform has disappeared, so the country will in a sense be “using up” the progress it has made. On a three or five-year view that probably makes little difference, but on a longer perspective it is more troubling. Hanging over Germany is the prospect of a falling population, while it already has a declining labour force. With an unchanged retirement age and limited immigration, the working population is expected to fall by about 15 per cent over the next 15 years.

You can see some projections for this in the bottom graph. This comes from a paper by the economist at the private bank Berenberg, Holger Schmieding, which looks at prospects for Europe to 2020. He is relatively optimistic about the EU in general, arguing that it could become “a more dynamic region with an excitingly diverse culture”. But he is concerned that Germany might become over-complacent and be outpaced by a reformed France and a resurgent Spain.

People will have a variety of views on this. Dr Schmieding is a German national who has spent much of his career abroad – he is currently based in London – and this doubtless gives him a perspective on Germany that we non-nationals cannot have. Many of us have been surprised and impressed by the German resurgence over the past decade because the country really was in a mess, with over 12 per cent unemployment in 2005. I suppose just as many of us over-emphasised the evident problems of Germany in the early 2000s, so there may be a parallel danger of over-emphasising its apparent strengths now. A country’s economic performance can flip remarkably swiftly, as we know here.

However, it is not very wise to bet against Germany. Time and time again it has appeared sclerotic, and time and time again it has surprised us by being able to reorient itself. It has been able to bear macro-economic burdens, such as the costs of incorporating East Germany and the entry into the euro at an uncompetitive exchange rate. But what it will find hard to do is cope with a declining population, for it has never faced such an experience in peacetime. So I think what we should be looking for over the life of this new grand coalition will be whether the country acknowledges the demographic mathematics and starts to adapt policy to this, or whether it will mark time and leave coping with this issue to a future government.

These are good years for Germany. The re-election of Angela Merkel as Chancellor (and nearly giving her an overall majority) showed the extent to which the voters felt they were being guided safely through the economic downturn and the eurozone crisis. Whatever view you take about the long-term future of the euro, there will be a period now of modest eurozone growth. Germany will benefit from that. The question is whether these good years will be used to prepare for tougher times ahead. At a fiscal level they will. There is not much doubt about that, for Germany is one of the few large economies at or close to running a surplus. But at a structural level it is not so clear that these years will be used wisely, and the first sight of the coalition agreement suggests they will not.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments