David Prosser: A picture of gloom that damaged Britain even before the cuts began

Your support helps us to tell the story

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

Louise Thomas

Editor

Outlook Let's nail one fib before George Osborne stands up to deliver the Comprehensive Spending Review today. The line parroted by the Chancellor andother Coalition ministers over the past week that not to adopt the cuts to be announced today will return Britain to the "brink of bankruptcy" just makes them look economically illiterate.

One can understand the desire to rewrite the narrative of the final years of Labour – and it would require an unhealthy dollop of revisionism to suggest that the previous government's record, particularly in its third term, was not one of increasing profligacy. Still, the claim Mr Osborne made on Sunday's Andrew Marr Show, that "before the election, actually people had a real question mark over Britain's ability to pay its way in the world", is plainly wrong.

Countries do not retain their AAA credit ratings from all three of the world's major ratings agencies if there are doubts about their ability to repay their debts. It is true those agencies had warned that Britain's top-notch rating might be undermined by a failure to take sufficiently robust action on the deficit. Standard & Poor's, for example, said in April: "The rating could be lowered if we conclude that, following the election, the next government's fiscal consolidation plans are unlikely to put the UK debt burden on a secure downward trajectory." But even it put the chances of a rating cut at only one in three (and the reduction would hardly have been to junk bond status).

Clearly, had the worst come to the worst, and S&P followed through on its threat, Britain's cost of borrowing would have risen. In fact, as Mr Osborne likes to point out, since the election, the rates paid by Britain for its debts have fallen. There can be no argument about that, or that the falls reflect the zeal he has shown in tackling the deficit. But if Britain's cost of borrowing is the only measure by which we should judge economic policy, why not swing the axe even harder today? The quicker we cut the deficit, the more borrowing costs will come down.

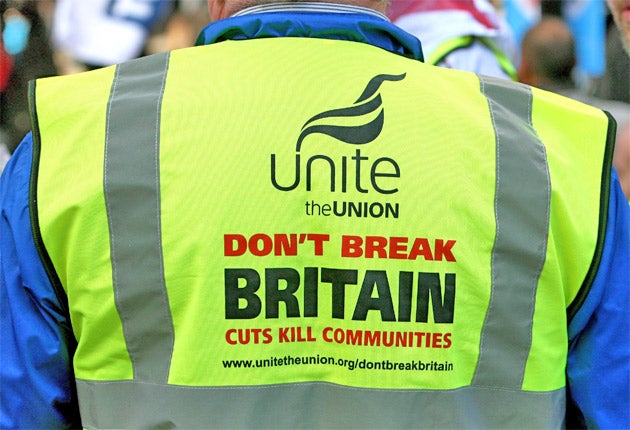

This argument is important because the Coalition has very deliberately sought to paint a picture in which there is no other choice but to take the most painful road towards deficit reduction – arguing that without cuts of the severity of those to be announced today, Britain will suffer financial meltdown.

Does Mr Osborne really believe that? The alternative strategy – to cut spending and raise taxes more slowly – would not automatically lead to a credit rating downgrade, assuming the deficit reduction programme was still credible, let alone to bankruptcy. And it would have allayed the fears of those economists, including at least two Nobel laureates, who fear the cuts will take us back into recession.

In truth, no one knows exactly what level of cuts we can get away with without stifling the recovery, just as no one knows exactly what level of failure to respond to the deficit would have prompted a downgrade. But Mr Osborne risks dropping us into the first of those soups with his insistence that no cuts that fall short of his would dunk us in the second drink.

It is rhetoric that has had dire consequences even before the detail of the cuts is known. For months now, all indicators ofeconomic confidence have been trending downwards. Consumers, increasingly fearful, have beensaving more (despite the pleas of the Bank of England's chief economist for them to spread their money around). House prices have been sliding as buyers stay out of the market. Businesses anticipate hiring fewer people over the next 12 months. The list of negative indicators goes on and on.

One can date almost exactly the moment when many of these benchmarks reached their inflection points: it was 22 June, the day of the emergency Budget. As soon as Mr Osborne spelled out the extent to which he was set upon dishing out the hair shirts, Britain began hunkering down. The Chancellor, in other words, began the conversation in which the country has been talking itself back into a downturn.

A more constructive way to bash the banks

While not strictly within the remit of the Comprehensive Spending Review, it seems inevitable that Mr Osborne will provide us with some guidance on what he has in store for the banks, particularly now that Alan Johnson, the new shadow Chancellor, has nailed Labour's colours to the mast of further tax raids on the City.

Certainly, hitting the banks will play to the fairness theme, of which Mr Osborne will want to make much. And in the context of the ongoing difficulties in persuading the banks to sign up to a new code on tax avoidance – certain institutions, which use complex schemes to minimise their tax bills, are thought to be reluctant – the City makes an even more tempting target.

The downside, however, to an additional levy on the bankingsector is that it would give them even more reason to deprive cash-strapped businesses of crucial credit. The banks no longer deny they are failing to extend credit to all those companies that deserve it – they have even launched a fund for small businesses, albeit with token sums available – but any new tax would give them even more ammunition as they argue that funding constraints leave them unable to lend more.

A wiser move, then, might be to announce tough new lendingtargets for the banks, expanding upon the targets already given to the two predominantly state-owned institutions, LloydsBanking Group and Royal Bank of Scotland. These should be nettargets – that is, absolute amounts of lending after repayments of existing loans – and the stick would be new taxes on those institutions which fail to achieve them.

The move would not be popular with the City – and the detail of the scheme would have to be carefully considered to ensure banks are not forced to lend to unviable projects – but this would be a more constructive way to target the sector.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments