David Blanchflower: The productivity puzzle hasn’t been solved and that’s very bad news

It is hard to see how productivity would rise in the face of Osborne’s unprecedented spending cuts

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Office for Budget Responsibility’s latest forecast, produced on the day of the Autumn Statement, was based on the assumption that the productivity puzzle was solved. The puzzle is that despite a big rise in employment and hours there has not been a corresponding rise in output per head or per worker. In fact, productivity has only been rising at around 0.5 per cent a year.

The OBR in its forecast assumes that productivity rises steadily to reach 2 per cent by 2019. But they also explore what they call a “weak productivity” scenario, in which the weakness of underlying trend productivity growth since the crisis persists over the next five years. This has enormous implications for the forecast. Instead of output growing by an average of around 2.2 per cent per annum for each of the next five years, it averages 0.9 per cent. That also has enormous implications for what happens to public sector net debt, which falls from 80.4 per cent in 2014/15 to 72.8 per cent in the central projection but rises to 86.6 per cent if the productivity puzzle isn’t solved.

The OBR never tells us what suddenly changes to solve the puzzle. It’s solved by magic, in the words of Tommy Cooper “just like that”. It’s all fixed by prestidigitation.

The OBR does admit that “the key judgement underpinning our forecast is about the long-awaited return of sustained productivity growth”. Real earnings are assumed to rise with productivity, so once the productivity puzzle is solved, just like that, and productivity rises, so will real earnings. The OBR forecasts real earnings will rise by 0.8 per cent in 2015 and by 1.4 per cent in 2016 and by 1.8 per cent in each of the next three years, despite the fact they have fallen by an average of more than 2 per cent a year for the last four years.

Problem solved? Well not exactly.

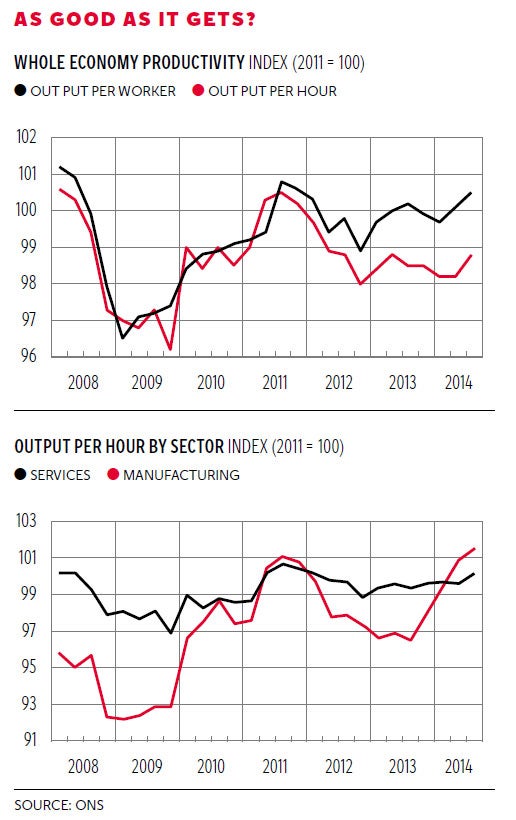

The Office for National Statistics has produced new productivity numbers for us to evaluate the OBR’s claims that the productivity puzzle has been solved overnight. Sadly it hasn’t; the conundrum remains. UK labour productivity as measured by output per hour increased by 0.6 per cent in the third quarter of 2014 compared with the previous quarter, but was 0.3 per cent higher than a year earlier. However, productivity remains about 2 per cent below its level prior to the economic downturn in 2008. This is an astonishing 16 per cent lower than had productivity maintained its pre-downturn trend.

The first chart shows that output per worker and output per hour have followed broadly similar paths, falling sharply through 2008 and then rising steadily as monetary stimulus was introduced by the Bank of England and the Labour government introduced fiscal stimulus. This upward path continued through 2011 until the austerity introduced by the Coalition took hold. This had the effect of once again decimating productivity, which fell sharply through the end of 2012, only picking up when George Osborne sensibly took his foot off the austerity peddle. Growth only came when austerity slowed. Since then output per hour has been broadly flat, although there has been a small pickup in output per worker.

It is hard to see how productivity would rise in the face of spending cuts that Mr Osborne outlined in his Road to Wigan Pier Autumn Statement, cuts which are unprecedented in living memory. The OBR said “total public spending is now projected to fall to 35.2 per cent of GDP by 2019-20, taking it below the previous post-war lows reached in 1957-8 and 1999-2000 to what would probably be its lowest level in 80 years”. More of the same won’t fix it.

The second chart shows productivity measured in terms of output per hour by sector and the story is broadly the same for economy as a whole. Manufacturing output per hour has increased in each of the latest four quarters and was 5.2 per cent higher than a year earlier in Q3, the fastest rate of increase since 2010. But it is still only up 2 per cent since 2011.

Services productivity has remained broadly flat for the last three years. So there is a glimmer of hope of a pick-up in manufacturing but essentially none in the much larger service sector.

The concern still is that the OBR’s weak productivity scenario may be as good as it gets because an even worse nightmare scenario of falling productivity can’t be ruled out in the face of further austerity.

The consequences of weak productivity continuing, as looks likely, will have consequences for wage growth, which will inevitably remain weak. An interesting new report on the labour market by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) helps to shed some light on whether wages are about to take off and whether an upward burst of labour productivity is on its way. It doesn’t appear so. The CIPD argues that wage growth is likely to remain in the 1–2 per cent range for most or all of 2015, although low inflation means average earnings might increase slightly in real terms. That seems plausible.

The CIPD asked employers about their pay expectations for the year ahead (in other words, September 2014 to September 2015). For those employers who expected to conduct a pay review in the coming year and who felt able to make a prediction about the likely outcome, the median pay increase was 2 per cent a year, the same as it has been since the winter 2013/14 survey. While 42 per cent of employers expected to increase pay in the year ahead and 10 per cent expected to reduce pay, 47 per cent did not know if they would have a pay review in the coming year or what the outcome would be (and lack of a pay review often turns out to be a de facto pay freeze).

According to the CIPD, one reason why employers are not expecting higher pay rises in 2015 – if they feel the need to raise pay at all – is “because many vacancies still attract plenty of suitable applicants”. No sign of a wage explosion or even much of an uptick at all here.

So the productivity puzzle remains and there is still no sign of a pick-up in wage growth despite all the wrong-headed claims to the contrary. Oh dear.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments