David Blanchflower: The problem for the Tories is that their economic plan has failed

There is widespread evidence that under-employment has risen even more sharply than the unemployment rate

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The economy remains weak and continues to slow. The decline in retail sales in March of 0.5 per cent caused an immediate drop in the pound and certainly did not help the absurd Tory claims of competence. On top of that the Institute for Fiscal Studies last week identified Tory plans for £30bn cuts to public services, even if they raise £5bn from a tax avoidance clampdown and £10bn of welfare savings. No wonder the Tories won’t answer questions on any of their dastardly economic schemes to inflict pain on ordinary people. For sure, if elected they will raise VAT and devastate basic public services.

The general election polls tell an interesting story. For all the money spent by the Tories, there has been no “crossover” in the polls and there certainly doesn’t seem to be one in the air. Labour’s ground game, according to Lord Ashcroft’s polling, seems to be working, especially in the marginals. The negative campaigning orchestrated by Lynton Crosby seems to have backfired. Despite what Michael Fallon and David Cameron suggested, the Ed Miliband I know is a thoroughly decent man.

Insulting the Scots is not going down well in Stirling and other towns north of the border, as I can tell you from personal experience. In Scotland there are more pandas than Tory MPs. The Scots didn’t vote for austerity, don’t want to leave the European Union and are pro-immigration as they have a declining population, so can hardly be blamed for objecting when more of the same apparently is headed their way.

The polls are tied, although there is a lot of day-to-day variation which looks like sampling error. But there are a few fairly stable patterns in the polling data.

Here I focus my comments especially on the YouGov polls, with numbers in parentheses from the 22-23 April YouGov/Sun poll. First, the Tories have seen little or no rise in their rating in the 700 or so polls since the beginning of 2014. Second, the Tories have big leads over Labour among those aged 60+ (12 pts) but a deficit among those under 60 (-7pts for 40-59 and -6pts for under 40). Third, the Tories’ main support is in the South-east (+12pts). They have deficits in London (-8), the North (-19) and Scotland (-33 to SNP and -6 to Labour).

The Scots, the Welsh and the Northern Irish are especially discontented, as are many in the North. It really is pretty obvious why: they have been left behind in the worst recovery in 300 years. Relative things matter, and even though everyone is hurting, England is doing better, especially in London and the South-east, in so many respects, not least in the labour and housing markets.

Just as in the eurozone the centre is doing fine and the periphery is not. It’s all different north of the Watford Gap.

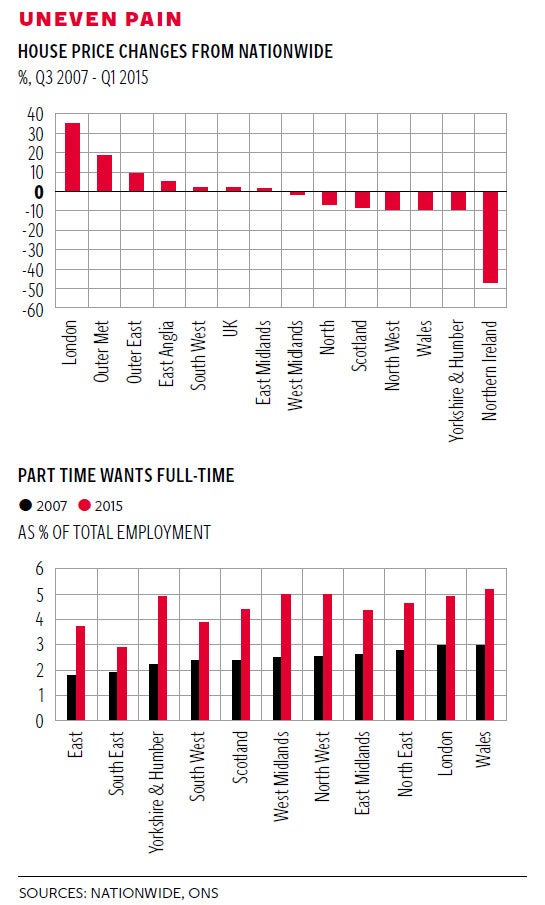

The housing market illustrates the split in the country. The first chart shows the difference in the recovery of house prices by region since the peak in Q3 2007. For the UK as a whole house prices are 2.4 per cent higher. But the story in London and the South-east is very different from the picture in the rest of the UK. House prices are up 35 per cent in London, 19 per cent in the outer metropolitan area and 10 per cent in the outer South-east. What a contrast to the rest of the country, where prices are 47 per cent lower on Northern Ireland, 9 per cent lower in Wales, Yorkshire and Humberside and the North-west, and 8 per cent lower in Scotland. The contrast between North and South is stark.

At the onset of recession at the end of 2007 the unemployment rate in the UK, taken as the average for October to December 2007, was 5.2 per cent. Jump forward seven years and in the latest data we have available for December 2014 to February 2015 the unemployment rate is 5.6 per cent, still a little higher than it was at the onset of recession.

Rates declined in the South-east, the East Midlands and London and rose everywhere else. Of particular note is the enormous rise in the North-east, from 5.6 per cent to 7.7 per cent, followed by Northern Ireland (+1.8 per cent), Scotland and Wales (both +1.2 per cent).

The employment rate for those aged 16 and over is also lower, from a high of 60.4 per cent in April 2008 versus 59.8 per cent in the most recent data. The UK has more people employed than was the case at the onset of recession but, given the rise in the number of people, the employment rate has fallen.

Over these seven years employment of people born in the UK is up 285,000 and 603,000 are from the EU and 420,000 from outside the EU. Total employment in Scotland is only 4,000 higher in 2015 than it was in 2007. In the North-east it is 2,000 lower. Employment in London is up 468,000.

There is also widespread evidence that under-employment has risen even more sharply than the unemployment rate. One simple indicator is the number of workers who are employed part-time who say they would like to work full-time.

For the UK as a whole this has risen from 729,000 in 2007 to 1,348,000 in the latest data released, down from a peak of 1,464,000 in March-May 2013. As a proportion of total employment this measure of under-employment has risen from 2.46 per cent to 4.34 per cent.

There is also a marked variation by region, as shown by the second chart, but in every case there has been an increase of at least 50 per cent. Under-employment is highest in Wales and lowest in London. This measure of under-employment remains well above starting levels in every UK region, which in large part explains why there is still no wage pressure. There remains masses of labour market slack outside the South and East.

The question is, what will happen in the final couple of weeks before the election? My suspicion is not much.

There haven’t been prior cases where there were multiple parties campaigning but most of all where real wages remain lower at the end of a parliament than at the beginning, so forecasting is nigh on impossible. The decline in house prices outside the South and East and the rise in unemployment and decline in employment are also likely to be major contributory factors. Stalemate.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments