David Blanchflower: Hallelujah – the monetary hawks have admitted their mistake

Wages in the UK are not just going to rise by magic, as the MPC and the Office for Budget Responsibility have been expecting

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The hawks lost. Hang out the bunting, hang out the flags, the Irrelevant Minority on the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee of Martin Weale and Ian McCafferty have finally seen the error of their ways and, at last, have stopped voting for a rate rise. Hallelujah. There have now been a total of 29 ludicrous votes for a rate rise since 2009 – 12 each by Andrew Sentance and Weale and five by McCafferty.

All of these hawkish votes were obviously mistaken and would have been especially devastating for anyone on variable rate mortgages. My Bernese mountain dog, Monty, could hardly have done a worse job. Empirical evidence has thankfully trumped economic theology. I fully expect the MPC’s forecasts to become more dovish, starting from the February Inflation Report, now the two lost sheep have come home!

The biggest economic news last week was the European Central Bank’s underwhelming announcement that it will start quantitative easing (QE). The MPC started QE in March 2009, six months after we started cutting rates sharply in October 2008 – six years later the ECB shows up.

This was not a game-changing big bazooka. Markets had priced in around €500bn already, and at €60bn a month from March through September 2016 it was a slight positive surprise, which generated a small fall in the euro and a tiny pick-up in European equities. It’s hard to see how this creates much inflation.

Of course, other central banks are not going to sit pat and watch the ECB weaken the euro unchallenged. I was live on Bloomberg radio last week when the Bank of Canada made a surprise cut in its interest rates. Other banks may follow, including the Fed, which has already signalled its concern about a strengthening dollar. The MPC’s next action may well be more QE rather than a rate rise, not least because shoppers from Belfast would find it a lot cheaper to take the short train ride to Dublin with its weaker euro.

Economic sentiment indicators such as the PMIs suggest that the UK economy started to slow in the spring of 2014, and now the labour market, which is a lagging indicator, is showing signs of decelerating.

The good news from the Office for National Statistics last week was the headline fall in unemployment, by 44,000 to a rate of 5.8 per cent, the lowest since July 2008.

Prior to the recession the unemployment rate was a sufficient statistic to summarise slack in the labour market, but sadly no longer. Most people need a professional guide to help them tiptoe through the labour market minefield.

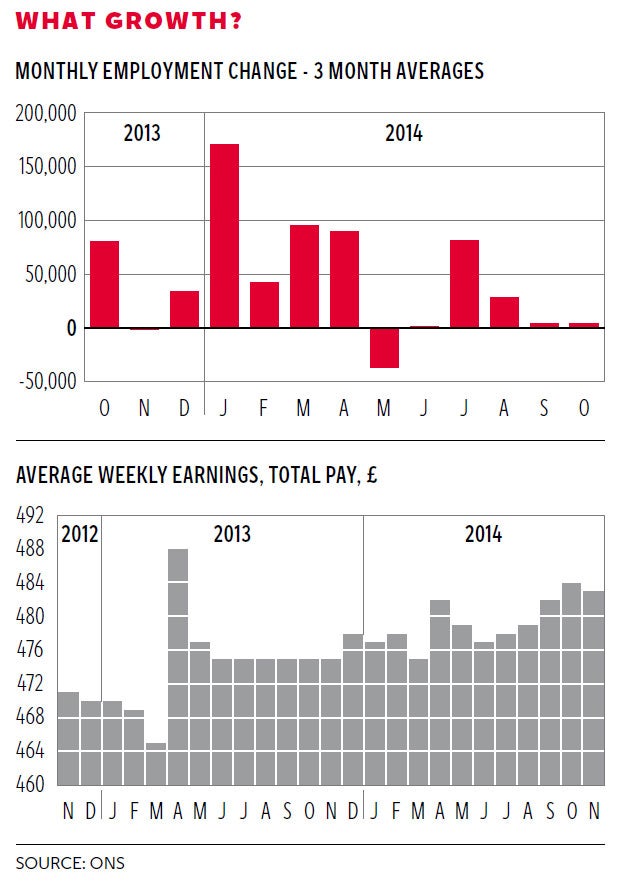

It turns out there was as much bad news as there was good. First, for the third month in a row, the participation rate fell on the month by 38,000, almost the same as the drop in unemployment, the majority of whom said they wanted a job. Rather than going directly to unemployment, workers became discouraged and left the labour force to become inactive. Second, there has been a rise in youth unemployment. Unemployment of 18- to 24-year-olds was up for the fourth month in a row, and 10,000 on the month. Third, the number of full-time workers fell on the month by 18,000, while the number of part-timers rose 16,000. Fourth, as the first chart shows, there has been a marked slowing in job creation, up only 4,000 in October and September. This contrasts sharply with an average increase of 47,000 a month in 2014 and 32,000 a month in 2013. Job creation has stalled.

Finally, much was made of the apparent pick-up in wages, which wasn’t really a pick-up at all, as the second chart illustrates. On the month, the Average Weekly Earnings (AWE) total pay actually fell, from £484 in October to £483 in November, and annual pay growth fell from 2.0 per cent to 1.8 per cent. The average of the last three months’ pay compared to that a year ago was 1.7 per cent. Private-sector total pay also fell on the month, from £482 to £481. Regular pay overall and in the private sector also fell, in money terms.

So what about claims of a pick-up? The 12-month change dropped from 2.0 per cent to 1.8 per cent, obtained by comparing AWE in November 2014 with November 2013. It is extremely likely that next month the change will fall even further because of a rise in the base month — which as can be seen in the chart, jumps from £475 in November 2013 to £478 in December 2013. To get as high as a 2 per cent growth rate next month on either the single or three-month measures, AWE for December would have to be at least £488, which seems unlikely. Weekly wages are up a sum total of only six quid over the last two years. Big deal.

We are still waiting for the ONS to announce its inevitable downward revisions to the AWE numbers for 2014, which are due soon. The reason this is important is because of the evidence from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings that the pay of workers in firms of under 20 employees, which are excluded from the survey used to construct the AWE, fell by 2 per cent in 2014, much lower than for workers in bigger firms that had pay increases. This was much less than the ONS had previously assumed based on the prior year’s estimates, which showed small and large firms having the same increases.

President Obama’s State of the Union address last week talked about middle-class economics, and the fact that ordinary people in the United States are not feeling the benefits of recovery. The hawks in the US, just as in the UK, have been claiming wages were about to pick up to solve the problem, but two recent data releases from the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed US wage growth also slowing to around 1.7 per cent per annum, about the same as the UK.

What is absent are solutions. Wages in the UK are not just going to rise by magic, as the MPC and the Office for Budget Responsibility have been expecting.

Middle-class economics has also come to town in the UK. A great question for any politician leading up to the general election is how they plan to raise living standards for the many, not just the few.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments