Trump one year on: Can the President really take credit for US economic success and record highs reached by the stock markets?

How much can he take personal credit for? And what will be the implications of decisions taken over the past 12 months for the economic future of the United States?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In his inaugural address in front of the US Capitol just over a year ago, Donald Trump outlined his creed that “protection will lead to great prosperity and strength”.

But how has the giant US economy performed under President Trump’s “protection”?

How much can he take personal credit for?

And what will be the implications of decisions taken over the past 12 months for the economic future of the US?

What has happened to the stock market?

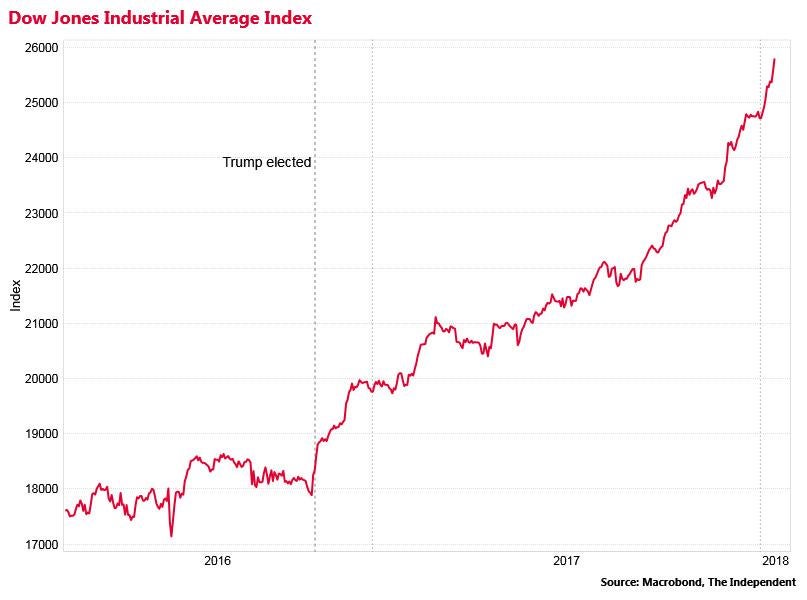

Trump’s favourite economic statistics over the past year have related to the price of US stocks.

“Dow goes from 18,589 on November 9, 2016, to 25,075 today, for a new all-time….Record fastest 1000 point move in history… Six trillion dollars in value created,” he tweeted on 5 January, one of many such market-related boasts to have emanated from Mr Trump over the past year.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average, an index of 30 large US companies, was indeed 18,589 when Trump won the election. And today it stands above 26,000. It’s also true that the rise of the index between 24,000 and 25,000 was the most rapid 1,000-point rise ever.

However, these records are less impressive than he implies. The Dow Jones is well-known to be a deeply flawed index. Its constituents are weighted by the face value of their individual shares, rather than the company’s market capitalisation, which is not a very accurate way to construct a measure of the advance of US companies.

Further, a 1,000-point jump in any index should naturally become more rapid the higher it rises, since this represents a smaller percentage gain, making this recent rapid increase not a particularly notable milestone.

Donald Trump was also switching between indexes when he claimed that the markets have put on “six trillion dollars” in value since he was elected.

The market value of the S&P 500 – a much broader and more sensibly calculated index of American firms than the Dow – rose in value from $19.6 trillion when he was inaugurated to around $25.1 trillion today. So a gain of around $5.5 trillion. The rise in the market capitalisation of the value of the Dow Jones over that time was a rather more modest-sounding $1.6 trillion.

How much credit should Trump get for this anyway?

It does seem that market valuations picked up sharply when he won the US election.

Wall Street analysts interpreted this as a response to his campaign promises of major infrastructure spending and tax cuts on firms – which were expected to be good news for US corporate profits.

We’ve now had the tax cuts, although not the infrastructure spending.

However, it could be that other factors, such as GDP growth expectations, are just as important as his policy pledges in boosting company valuations.

The global economy picked up surprisingly strongly in 2017. It is relevant that European stock markets are also up strongly since the US election, something that cannot credibly be attributed to Mr Trump.

What about jobs?

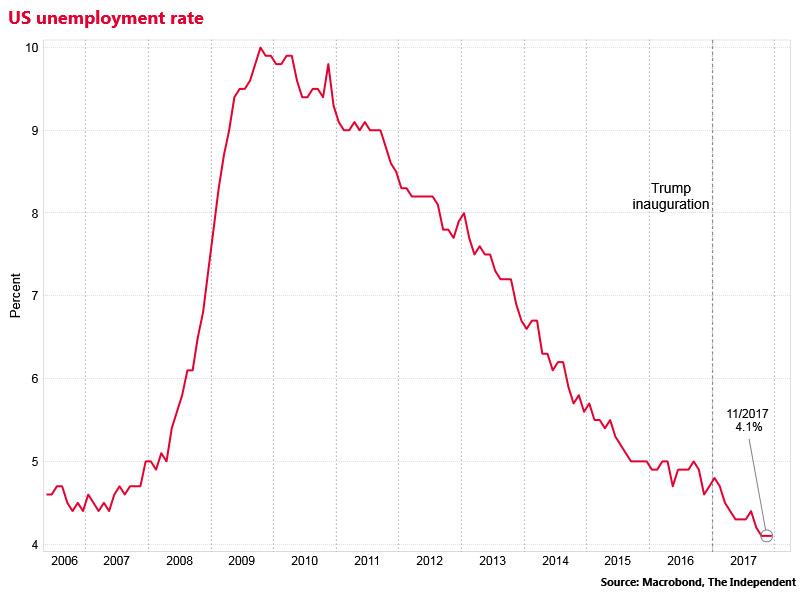

Donald Trump has also frequently boasted about job creation under his administration.

“Jobs are coming back to America,” has been one of his regular refrains.

Monthly job creation has certainly been strong under his presidency, averaging around 170,000 a month.

And the official 16-plus jobless rate has fallen to 4.1 per cent, down from 4.8 per cent last January and the lowest since 2000.

Yet it’s important to note that the US jobs story did not begin in 2017 when Mr Trump took office.

There was considerable momentum from President Obama’s presidency, who oversaw the jobless rate fall steadily from a peak of 10 per cent during the 2009 recession.

Despite some high-profile examples touted by Mr Trump, there is also no evidence of a major move from US manufacturing firms, as a whole, to switch jobs in their international supply chains back to America.

The opposite in fact. In the year since he was elected, around 93,000 jobs have been recorded by the United States Department of Labor as lost to outsourcing or trade competition, which is slightly higher than the average of about 87,000 in the preceding half decade.

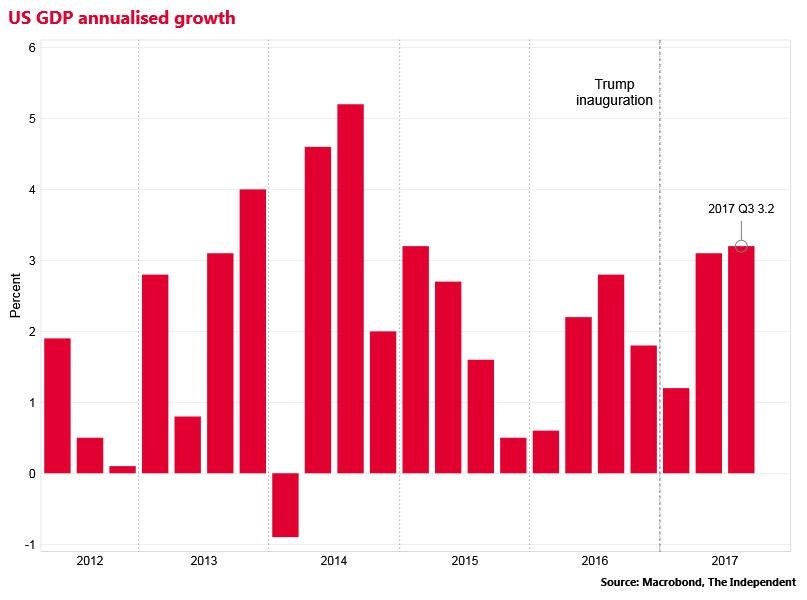

What about GDP?

This has been a story of improvement.

In the first quarter of 2017 the US economy was growing at an annualised rate of 1.2 per cent. That had strengthened by the third quarter to 3.2 per cent.

The International Monetary Fund is projecting full-year US growth for 2017 of 2.2 per cent, up from 1.5 per cent in 2016 and the second biggest expansion in the G7.

And it expects growth in 2018 of 2.3 per cent, which would be the highest among the rich country club.

What about those tax cuts?

“Massive tax cuts for working families across America,” was how Donald Trump described the tax bill, which passed the senate in December, in the first and only major legislative success of his presidency.

The bill lowers the top individual income tax rate from 39.6 per cent to 38.5 per cent and slashes the rates for most lower-income tax brackets too.

Other major changes are a doubling in the exemption of the US version of inheritance tax, and increasing access to a child tax credit.

For firms, the bill cuts the headline US corporation tax from 35 per cent to 20 per cent.

This may – or may not – stimulate domestic corporate investment.

It will certainly increase the US budget deficit. And independent analysts have dismissed the claim from the president that the legislation will primarily benefit ordinary Americans.

The Tax Policy Centre has produced a distributional analysis of the impact of the senate’s tax bill. This showed that it would reduce taxes, on average, for most Americans between 2019 and 2025. But by far the biggest beneficiaries of the tax cuts over the next decade would be the top 1 per cent of earners, and the top 0.1 per cent of American households, including Mr Trump himself.

And by 2027 taxes would actually rise for the lowest-income groups.

What about the future?

There is no gainsaying that the US economy has performed strongly in the first year of Donald Trump’s chaotic presidency.

But his claims that he can take credit for all movements in the stock market and the jobs market must be taken with a large pinch of salt.

His sole legislative achievement will deliver nothing much to the American middle classes on whose behalf he promised to govern a year ago.

In the longer term, Trump’s anti-immigrant legislative manoeuvres, inflammatory rhetoric and authoritarian posturing risk damage to America’s soft power and prestige around the world, which could have a lasting negative impact on the country’s growth potential.

And if he starts to deliver on his protectionist promises over the next few years, he could still do grave damage to the integrity of the liberal global trade system which, again, will ultimately be harmful to the American economy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments