The Big Question: Is quantitative easing creating more problems than it is solving?

Why are we asking this now?

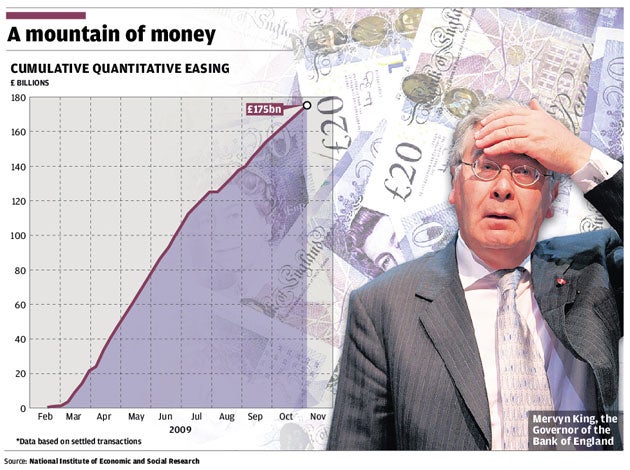

Because the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee – which comprises bank officials as well as outside independent advisers – has voted to expand its policy of "quantitative easing", colloquially known as printing money, by a further £25bn to a staggering £200bn. That's almost three times the initial dose agreed in March, when the Bank thought that £75bn ought to do the trick, though even then it thought it might take up to £150bn. Evidently, the economy has not been responding to the medicine with the alacrity once hoped for.

So what exactly is 'quantitative easing'?

An unlovely name for a fairly straightforward idea. The "quantitative" bit refers simply to the fact that the Bank is directly altering the quantity of money in the economy, rather than the price, or interest rate, which has been set at 0.5 per cent since March, the lowest level in the Bank's 315-year history. The "easing" bit merely means that the Bank wants to make money easier.

Given that "negative interest rates" are very hard to engineer, and official rates are already about as close to zero as practicable, the Bank's minds have turned to how to inject more money and spending. The answer – QE as it's known for short – is supposed to provide an adrenaline shot for the economy, a direct injection of money to help boost demand and spending and, in due course, get inflation back to the Bank's 2 per cent target. Although it isn't far off that number now, the Bank thinks underlying inflation in the economy will continue to subside given the weak state of demand.

So are the bank's printing presses working flat out?

That would be an old-fashioned way of going about things. Nowadays money is about much more than the notes and coins in circulation. Think of the money you hold in your bank account, which is electronic money, numbers on a spreadsheet or some other piece of software, with not even a piece of paper with the Queen's image on it to back it up in some vault, let alone gold or silver. Magical, really.

How do you increase the amount of money in the economy?

The way the Bank of England has chosen to do it is to create "central bank money", offering money to holders of government securities, or gilts, at twice weekly "reverse auctions". Bodies such as pension funds are offered a very good price for their gilts, and they sell them to the Bank of England. The money the pension funds receive is then banked at Barclays or wherever, and the account that Barclays holds with the Bank of England, a sort of bankers' bank in this case, is credited.

No picturesque, nicely engraved bits of paper fly around. Even the gilts have been "dematerialised" nowadays, so it is all computerised, but real nonetheless. Smaller quantities of bonds and other securities issued by the private sector have also been bought by the bank, on the same principle of putting money into the economy.

But won't this process cause inflation?

Yes! That is the general idea, at least if you think that deflation – falling prices – are now the problem rather than rampant inflation, as the Bank does. The Bank is worried that demand in the economy is so weak that we won't even see inflation going back to the 2 per cent target as next year drags on. The Bank has to work with unusually long and variable "lags" with QE. It doesn't know when it will make its presence felt, as the country has never before tried this policy in these sorts of conditions. The Bank has indicated that it takes at least six months for the policy to work through and maybe much longer. Some people are still worried that the Bank's policy will deliver higher inflation over the next few years, if it isn't able to reverse its policy easily – the so-called exit strategy.

So how does it work?

Just by putting more money, which ought to get spent somehow, into the economy. The main effect has been to boost the capital markets, ie shares and corporate bonds. Hence the remarkable recovery in the stock markets since their low point in the spring, though some see this as just new, unsustainable "bubbles". The idea is that companies are able to raise funds and spend them on new investment, and the effects trickle down through the rest of the economy. The mechanism is fairly easy to see. The Bank's appetite for huge quantities of gilts pushes their price higher and thus depresses their yield on any given "coupon", or nominal interest rate. As pension funds and other investors look at the pitifully small returns now offered on gilts, they are more inclined to invest in – say – blue-chip shares or top rated company bonds. But all securities seem to have enjoyed some sort of benefit. Even the banks have been able to raise extra cash through issues of new shares, and some heavily indebted companies that thought they might go under have been able to persuade their bondholders to swap those debts for shares. We have even seen some revival in the market for a cleaned-up version of mortgage-backed securities, which got such a bad name for themselves during the credit bubble.

Why isn't the economy growing then?

A few problems seem to have grown up. First, QE appears to be helping really big companies who have access to the capital markets, but has been less use to smaller firms and first-time home-buyers, who rely on bank finance. There was some suggestion from the Bank at the beginning of the policy in March that the banks would lend more as they found themselves with more money, but that seems not to have happened – presumably because so many of our banks are bust or nearly bust.

Second, even in the case of the bigger companies, there is some evidence to suggest that all they are doing with the cash they raise is to pay off their debts, rather than spending lots on new plant and machinery or hiring new staff.

Third, we seem to have suddenly lost our historic appetite for consumer debt. We've been paying our credit card bills and bank loans, and we are saving more too, despite the absurdly low interest rates being offered by banks and building societies. The argument here is that the Bank should have done even more, and sooner, to prevent this "deflationary mindset" taking hold.

What if QE fails?

It's fair to say that we would probably be in even worse trouble if the Bank of England (and other central banks around the world) had not pursued this policy – though it is impossible to imagine precisely "what might have been". You could argue that QE cannot fail in the sense that there is always more that the Bank can do. Mr King and his colleagues possess a theoretically unlimited capacity to buy gilts and other assets with money they create at the stroke of a computer keyboard. But the efficacy of the policy isn't necessarily increased by just throwing more money at it.

Given the parlous state of the public finances, the Government has no scope to spend our way out of trouble, even with the Bank buying its debts (indirectly). So – worryingly – the authorities seem to be running out of ideas.

Will QE be the answer to our problems?

Yes...

* It has already boosted stock markets, boosted asset prices and lifted confidence

* The scale is so large – an injection of £200bn – that it must have some sort of impact

* Large companies are finding access to cash much easier by raising money on the bond markets

No...

* It does little for small businesses and those first-time buyers who have been cut off by the banks

* The money is just creating new bubbles in the stock and commodity markets

* The figures speak for themselves. Even with QE, the economy is still contracting

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments